Let us be your fantasy: How Fantazia brought UK rave to the masses

One of the first legal UK mega-raves to bring dance music culture to the masses was Fantazia. With its emphasis on spending big production budgets on the whole rave experience, as opposed to predominantly on DJ fees, it was a forerunner of the mega-festivals of today such as Tomorrowland, and Glastonbury’s Block9 area. DJ Mag speaks to Fantazia co-founder James Perkins about the rave brand’s genesis, highlights and ongoing legacy

By the early ’90s, dance music in the UK was already a complex beast. US house and techno cross-pollinated with synth-pop, rare groove and soundsystem culture, in clubs, free parties, warehouses and shebeens, not to mention on pirate radio. The UK-specific sound that dominated this embryonic era, and brought rave culture to the masses, was breakbeat hardcore. Huge licensed events sprung up, sometimes enticing tens of thousands of people, some perhaps not intrepid enough to commit to nights of chasing phone lines and facing down the police.

After the groundwork was laid in the late ’80s by illegal promoters like Biology, Energy and Sunrise, major players capitalised on this booming industry with ambitious, legal events. UK hardcore veteran Slipmatt insists that his brother’s Raindance events were among the first to make the leap to licensed parties in 1989. By 1991 it was a crowded marketplace, with names like Dreamscape, Universe and Perception. With the music also settling into clubs while the free party scene raged on, it’s remarkable how many people were out there chasing a good time.

And it really did seem to be a good time – now immortalised in a plethora of VHS rips on YouTube, showing endearingly un-self-conscious people having a blast. Every seasoned raver has their own perception of when the culture was at its peak, why it happened and how things changed (for better or worse), but there’s a widespread consensus that the years around 1990-1994 were some of the best. The scene still had a whiff of innocence and optimism to it: before the government legislated against the culture, opportunists brought negative energy and money-minded cynicism to the scene, and the music splintered into more specific, tribal factions.

One of the boldest promoters of that golden era was Fantazia. In the face of dance music’s underground roots, Fantazia was unabashedly big business, facilitating rave’s acceptance in mainstream culture. The brand changed over time, reacting to trends in the scene and emergent club industry, but their classic run of events in the early ’90s remains epochal.

A trip back in time to the roots of Fantazia stirs up the collective euphoria of their knockout mega-raves and club-nights, left lingering in the collective (albeit hazy) memories of a generation. But it’s also a story of UK dance music’s awkward advances towards big budget events and production, foreshadowing the boom and bust of the superclub era and the clamour of the modern festival scene.

ROOTS

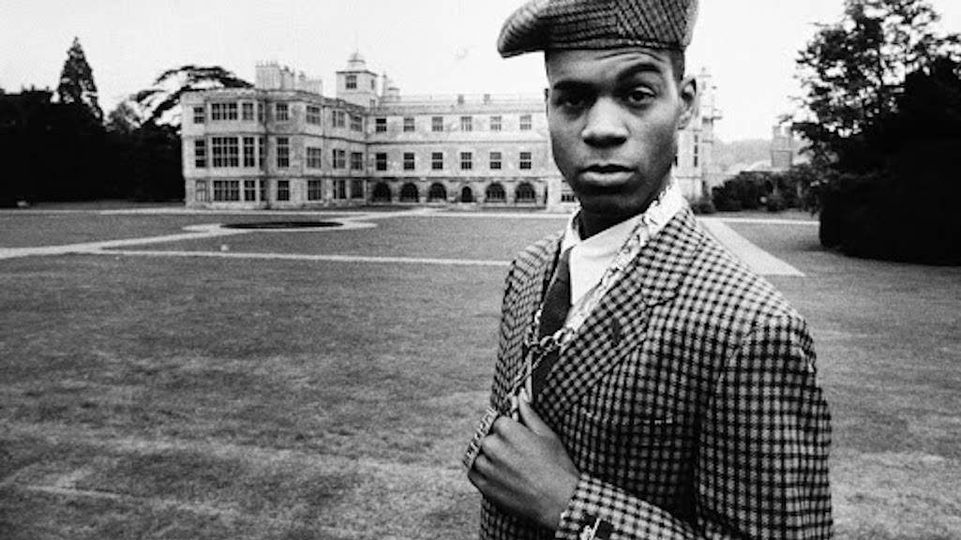

These days, the source of Fantazia can be found in the unlikely location of Aynhoe Park in Oxfordshire. The extravagant stately home belongs to James Perkins, one of Fantazia’s original founders, who started out throwing black-tie events as a schoolboy in Cheltenham. Now a middle-aged man decked out in a casual suit, Perkins takes pleasure in showing DJ Mag around his opulent home. He’s welcoming and relaxed as we sit in his study to drink coffee and talk under the watchful gaze of a stuffed giraffe, tapping the arms of his Gucci sunglasses on his teeth as he ruminates on a point.

While he name-checks the importance of the early free parties happening around the M25, and looks wistfully back on trips to Shelley’s Laserdome in Stoke-on-Trent and Quadrant Park in Liverpool, he drew most of his inspiration from big all-night clubs in mainland Spain and Ibiza. “I went to these open-air places that had lasers that fire out to sea, and then there’d be a mirror on a fishing boat and it would come back again,” Perkins recalls. “I was like, ‘Woah! When I get home, I want to do that’.”

Perkins founded a club-night called Trance in Cheltenham in 1988, which he ran successfully for two years booking acts like acid house evangelist Ellis Dee. He teamed up with fellow Cheltenham promoters Chris Griffin and Gideon Dawson to throw Perception on September 1st 1990 at Bletchingdon Park in Oxfordshire, off the back of a license Perkins had for another black-tie event. The line-up included 808 State live, Fabio and Grooverider. Unfortunately for the young team, they weren’t prepared for how to handle the security.

“These security guards had guns in the boot and said, ‘If you don’t give us all the money you’re dead’,” Perkins explains. “I was like, ‘Are you fucking joking? You hired these people and trusted them?’ But we got lucky. We had an amazing line-up and the event itself was fantastic.”

INCEPTION

The first Fantazia event was held at the UK’s first legal all-night club, The Eclipse in Coventry, on April 19th 1991. The flyer promised “12 hours of musical delight in 10,000 square feet of unique visual madness”, with a line-up that included Jumping Jack Frost, Carl Cox, Sasha, and scores more. Off to a strong start, Fantazia made an even bigger impression with their New Year’s Eve party at the Westpoint Centre in Exeter.

“Westpoint Exhibition Centre was normally used for bathroom or kitchen conventions,” explains Perkins. “At the age I was — 20, 21 — it was pretty exciting to be responsible for a night out for eight and a half thousand people, with all of the peripheral chaos, positive and negative stress that goes with it. But that’s all part of the excitement.”

Westpoint chief executive Chris Cullen even praised the event in a local newspaper at the time, framed by the article’s slightly incredulous tone that the sceptre of a large-scale rave had passed off without incident. “It was incredible to see so many youngsters having so much fun and there was not a single problem. It was a marvellous evening and the only time we went above the agreed noise level was when the music stopped at midnight, two pipers came in and we all sang ‘Auld Lang Syne’.”

Fantazia weren’t the only events to get going on a grand scale in 1991. Dreamscape held their first event at what would become fabled rave spot The Sanctuary in Milton Keynes, and Universe emerged out of the West Country free party scene. Everyone we spoke to about Fantazia mentioned Universe in the same breath — the two events occupied a similar space in the booming rave market.

“For the West Country, Fantazia, Universe, they were the ones,” says Bristol-based Joe Peng, who spent the early ’90s MCing at raves. “They had every DJ worth listening to, three or four arenas, lights, dancers. Impressive is an understatement. It was immense.”

“The party at Matcham’s is widely considered one of the best events Fantazia organised — a perfect combination of Ibiza-like sunny weather, and the striking setting in the centre of a raceway track.”

UNDERWORLD

Free parties always operated with the risk of being shut down. One of the big appeals of licensed events was the stability they provided. “Most of the big events we did around 1989 — Sunrise, Energy, Raindance — it was hit and miss whether they would go ahead,” says Mark McKee from Fantazia staples Ratpack. “Then you started getting people like Fantazia who would be consistent in putting these big events on and it would go without any hassle.”

“When we did Westpoint Exhibition Centre, I’d mastered the art of getting the licensing with the council,” Perkins explains. “To get these 8am licenses I needed to go in there and be taken seriously. I didn’t look like somebody from The Prodigy. I was a smartly dressed young guy that seemed to have all the answers to their questions. I found a lawyer who came and represented me in a formal way.”

Perkins paid particular attention to the security he employed for his events, mainly using a London firm with links to the boxing world called Top Guard. This was new territory for both parties — rave culture coming under the scrutiny of an authority presence, and security teams working out how to deal with the peculiarities of the party scene. “We all prefer working with ravers,” said Top Guard manager Terry O’Neill in 1993. “They are absolutely no trouble whatsoever. The only problems at raves are the muggers. And we are aware of these groups and deal with them when we catch them.”

It’s no secret the rave scene was infiltrated by criminal elements looking to exert influence over successful club owners and promoters. Perkins received regular death threats, but rather than bring the gangs into the fold he surrounded himself with more security. “I realised I was getting involved in a dark underworld of people I didn’t want anything to do with,” Perkins admits. “I’m like, ‘I’m nothing to do with drugs guys. I put on a party, I make money out of drinks and tickets, and I leave your town’.”

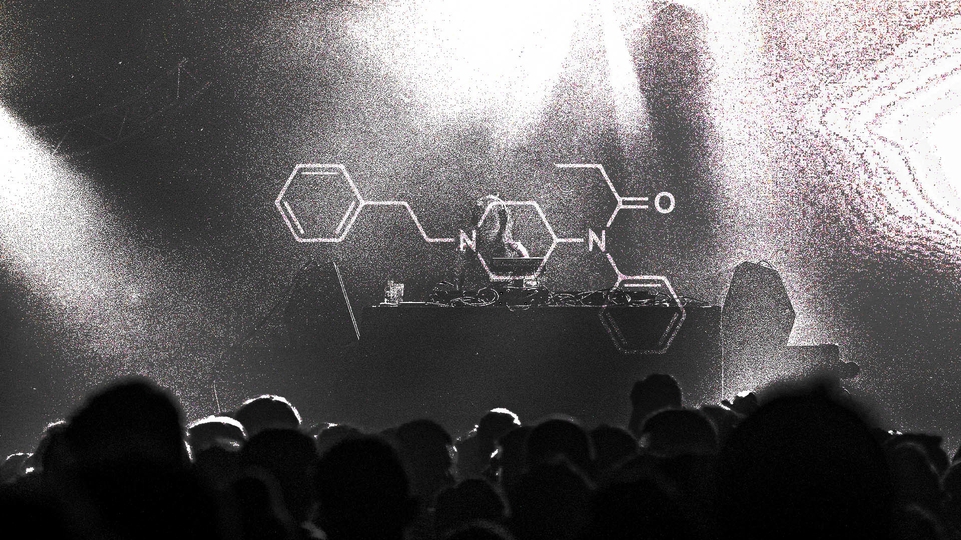

That said: rave culture was defined as much by ecstasy as the music, the events and the people, at Fantazia as much as any other party. It’s a topic that makes Perkins a little uncomfortable — he’s quick to point out they had searches and drug amnesty bins on the door as part of their license conditions. “I’m aware that people did [ecstasy],” he concedes. “That’s why I had medical support on site. But I’d like to think you could go to our event and be entertained, as I was, without needing to.”

TRIPLE WHAMMY

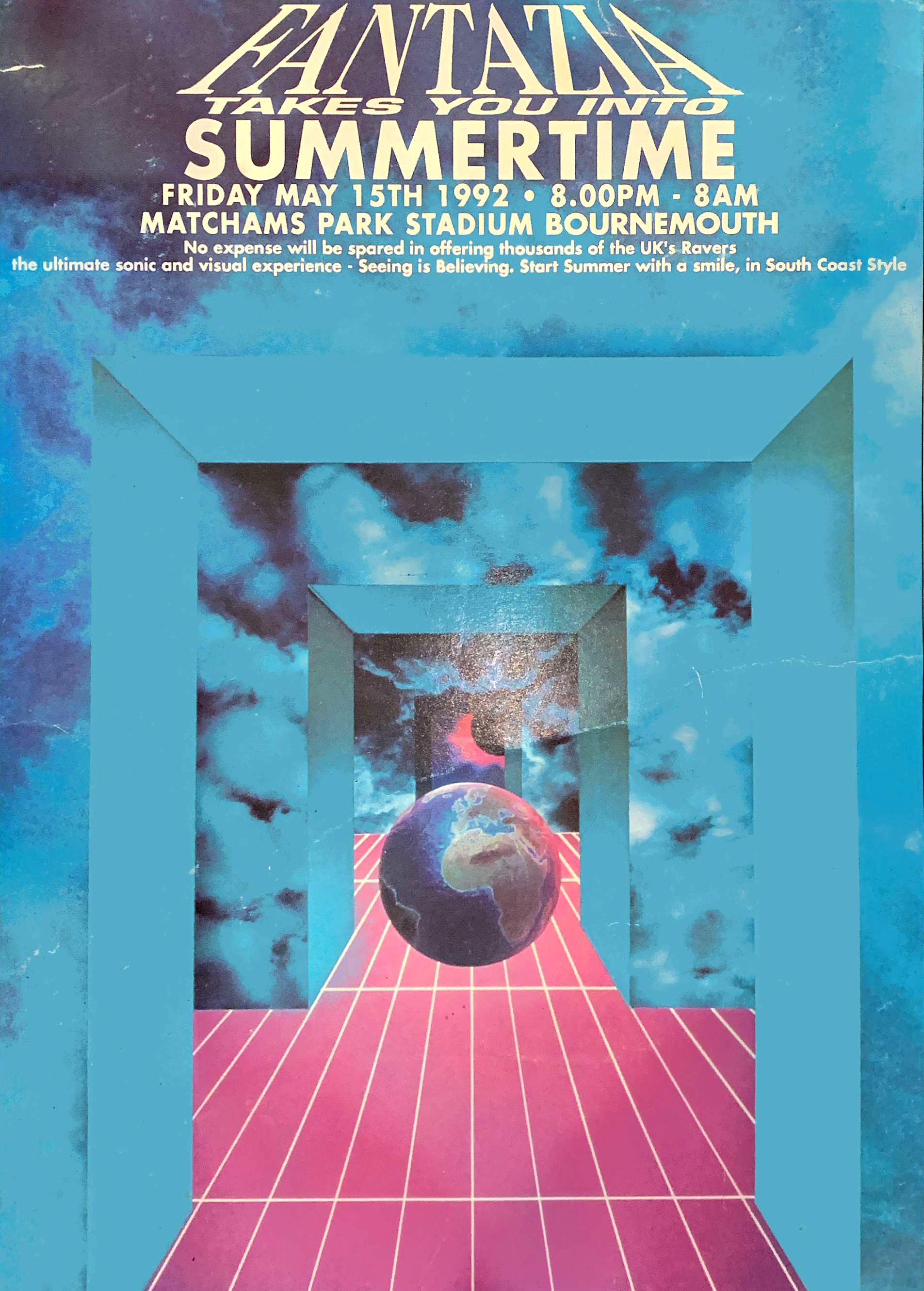

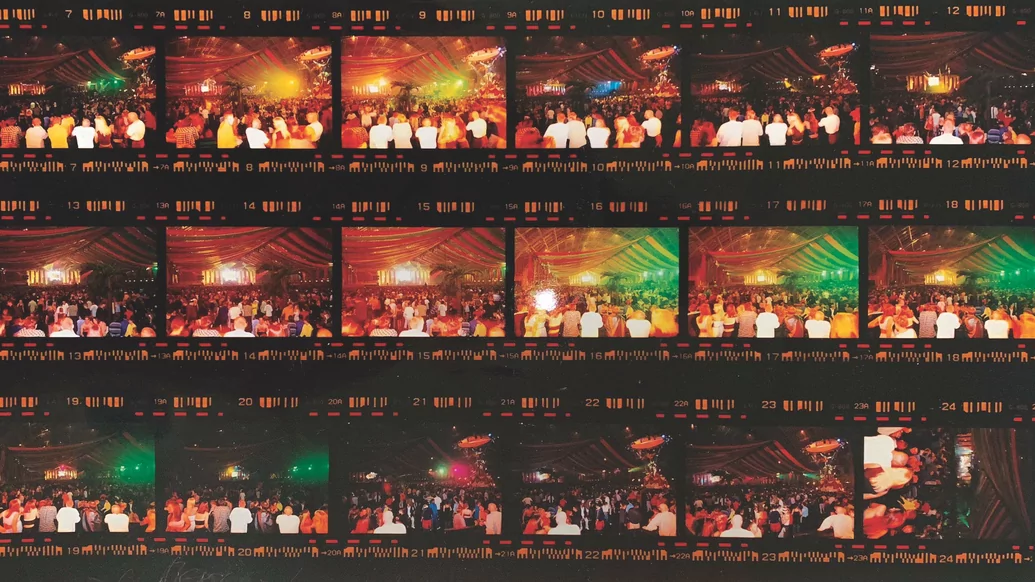

By the summer of 1992, Fantazia had started tagging their events with experiential titles and retro-futuristic flyer designs that placed the emphasis on the brand rather than the line-up. Having returned to the Westpoint Centre for a party dubbed The Second Sight, they next organised Fantazia Takes You Into Summertime, at Matcham’s Park Stadium in Bournemouth on May 15th. The license was for 8,000 attendees but most estimates suggest the number was closer to double that on the night.

As well as people jumping the fence, Gideon Dawson had printed and distributed extra tickets to avoid having to travel the country to shift smaller amounts as shops sold out. Dawson was fired from Fantazia after this blunder, and went on to run the Obsession events instead. But despite the extra numbers, the wheels didn’t come off. The party at Matcham’s is widely considered one of the best events Fantazia organised — a perfect combination of Ibiza-like sunny weather, and the striking setting in the centre of a raceway track.

Ellis Dee, Easy Groove, Top Buzz, Ratpack, Slipmatt and Ratty — a staple roster that soundtracked the main run of Fantazia events through 1992 — pushed livewire hardcore, all Mentasm stabs, smatterings of piano, chunky square wave basslines and rattling breakbeats. Barely a set went by without a banger by The Prodigy being dropped, and hits like 2 Bad Mice’s ‘Bombscare’ were ubiquitous. Clearly, events on the scale of Fantazia were fair game for playing big tunes.

The sound evolved as quickly as the events upscaled, too. “For me, 1990 was the bleeps and bass LFO sort of sound,” says Slipmatt. “That gradually moved into a Euro-y hardcore sound, a bit more four to the floor. Then breakbeats started coming in more as we went into ’92. It stayed hardcore, but then that jungle element got more prominent and everything sped up from 130bpm up to 160bpm by the end of ’92.”

Claire Henderson, who was writing for leading early ’90s ‘zine Ravescene, recalls the Bournemouth event fondly. “The MC, Robbie Dee, was literally on a wire flying over the crowd. Back then we would hand out Ravescenes afterwards, so you’d feel the energy of everybody as they were leaving the party.”

The review in the following issue of Ravescene was complimentary, and interestingly sparked nostalgia for the illegal rave boom of the late ’80s — a sure sign that the culture was undergoing transformation with the advent of licensed raves: “The first impression was unbelievable. It was almost like going back in time to the days of old. Who remembers Sunrise, Biology etc? This definitely is as close as you could get in this present time of raving to finding out what it used to be like.” Slipmatt remembers Matcham’s, for sure: he DJ’d to over 16,000 people as the sun rose.

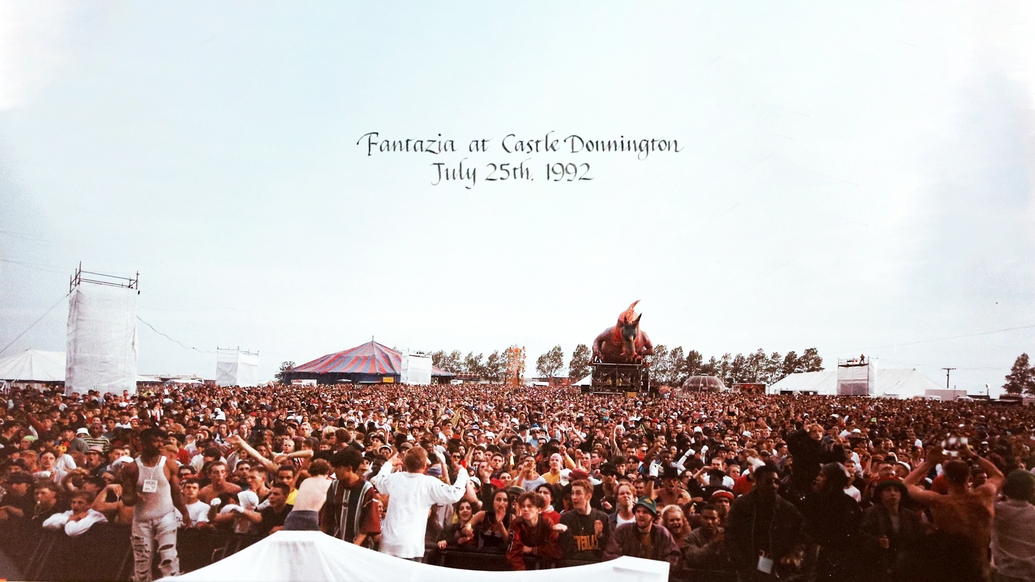

“With its castle stage and a huge inflatable dragon provided by Air Techs (who also worked with Pink Floyd), this event reached to levels of spectacle at a venue generally seen as the home of heavy metal events like Monsters Of Rock. It was an ambitious achievement, not least because the license was granted just two and a half weeks before the event took place.”

Fantazia Takes You Into Summertime was also the first Fantazia that Ratpack were booked for. They were caught in the traffic getting towards the venue and only managed to make it for 20 minutes of their set. “Someone in a car in front of us said they were us,” McKee reveals. “We didn’t want to scupper someone’s little plan. I only played maybe six records maximum, but the crowd just went nuts.”

Fantazia quickly followed up the success of Matcham’s in late July with Fantazia Takes You One Step Beyond: at Castle Donington in Leicestershire, for 25,000 people. With its castle stage and a huge inflatable dragon provided by Air Techs (who also worked with Pink Floyd), this event reached to levels of spectacle at a venue generally seen as the home of heavy metal events like Monsters Of Rock. It was an ambitious achievement, not least because the license was granted just two and a half weeks before the event took place.

Making up for their curtailed appearance at Matcham’s, Ratpack’s closing set from 7am ‘till 8am at Donington goes down in rave history. The magnitude of the situation wasn’t lost on McKee. “By that time DJing was like water off a duck’s back for me,” he says, “but I was so nervous at Donington I actually vomited. I don’t know if that had anything to do with the little ‘un I had earlier on that day.”

The rest of 1992 was busy for Fantazia, and they rounded it off with a New Year’s Eve event at Littlecote House in Berkshire. It stands as one of their most infamous events, where they struggled to deliver on the promises made on the promotional flyers. At the time, the sanctity of the scene was a hot topic continually evaluated in the ‘zines. Longer-running promoters Raindance even drew up the Ravers Charter, which declared: “if we don’t provide any attraction or acts mentioned on the flyers or provide a reasonable and suitable replacement we will give you a cash back guarantee.”

Perkins looks back a little sorely on Littlecote House (Fantazia Takes You Into 1993). He wanted the three big tents he’d erected to be connected, which was refused by fire safety officers. Bad weather led to the ground being churned up by heavy machinery in the set-up which resulted in a muddy, damp setting for a 10,000-strong party. Some argue the flyer implied the event was in the house itself. Rave magazine Eternity ran a scathing review of the event in their third issue:

“All in all we feel a bit let down and it’s pretty obvious that a lot of ravers out there do as well. We still enjoyed the night, but if they are going to put something on the flyer it should be there. Anyway, we think Fantazia have got a lot of work to do now to get faith back.”

CHANGE

Heading into 1993, Fantazia kept their heads down and focused on the club residency at The Old Cinema, and threw a second birthday celebration at The Sanctuary in Milton Keynes — Ratpack MC Evenson Allen even burst out from a giant birthday cake for the occasion. The other major Fantazia event in the UK that year was The Big Bang at Glasgow SECC in November, a stadium event that Perkins looks back fondly on. However, divisions in the hardcore scene were emerging as more specific sounds took shape and tribalised ravers, the rise of jungle most memorably.

“The music became quite fragmented,” says Perkins, “and I hated jungle. Don’t get me wrong, I liked Fabio and Grooverider, but overall it got very dark. If you took me back to Shelley’s and Sasha, and that sort of sound, that was much more peace and love and happiness. For 16,000 people, you needed the line-up to have a greater appeal.” McKee agrees. “1992-93, this transition started,” he remembers. “The BPM started getting a bit faster and... it was all getting a bit moody. We just wanted uplifting tracks to play, so we stuck to our guns with that and always have.”

Claire Henderson credits a number of different factors with the way the rave scene started to dip, from a dearth of good quality ecstasy around 1994 to the aftershock of the infamous free party on Castlemorton in the summer of 1992. “The police didn’t give ravers a hard time until Spiral Tribe decided to put on Castlemorton,” she argues. “It wasn’t on television worldwide [until then]. The police were not going to have it. Spiral Tribe hands-down wrecked the rave scene for me. Really, the last good year for raving was 1992 in my opinion. It limped on for me until 1995.”

THE BRAND

There’s no doubt Fantazia embedded itself firmly in UK youth culture. The brand pushed its merchandise hard and fastidiously documented its flagship events with VHS releases and tape packs. In 1992, they were even drafted in to organise a rave scene in a mansion for an episode of stuffy crime drama Inspector Morse. By 1994 the splintering of the scene changed the landscape for the mega-rave model. Fantazia focused some energy on Australia for six months. Perkins and Griffin organised DJ tours down under, but first they threw a typically mammoth New Year's Eve event at the Homebush Stadium in Sydney with Moby, Dave Angel and Ratpack.

After the forays into Australia, Fantazia shifted its focus towards releasing music. They had established a record label in 1992 to carry compilations like ‘The First Taste’ and ‘Twice As Nice’, as well as Ratpack’s ‘Lords Of The Dance’ LP. By 1994 they were releasing swathes of CDs, including ‘The House Collection’ series that symbolised a shift away from hardcore.

Meanwhile, the Fantazia stamp adorned club gigs at places like Bowlers in Manchester, The Ritzy in Leeds, The Palace in Blackpool and the FUBAR in Stirling, but nothing quite on the scale of the peak 1991-93 run. There were still big achievements to come, from hosting the backstage after-party for Oasis’ landmark Knebworth concerts in 1996 and a revival ‘Return Of A Legend’ event in 1997 at the G-Mex Arena in Manchester, to holding a 16-date residency at Privilege in Ibiza in 1998.

Despite the top-tier DJs they worked with, Fantazia’s foundations were built on its own identity rather than that of the talent they worked with. “It was all about the brand,” says Perkins. “‘Fantazia takes you into this’, or ‘takes you one step beyond’. To have 10 DJs on the poster just looked like a shopping list of names. For me people needed to trust the brand because we were going to bring you a big production you hadn't seen before.”

The core Fantazia team of Perkins, Griffin and Dawson splintered in the early ’90s, although Griffin remained successful after launching superclub brand Godskitchen in 1996. Dawson remained committed to music throughout his life, although battles with substance abuse ultimately led to his death in April 2019, when he died after taking “a cocktail of drugs” in his Cheltenham home.

Perkins has kept a connection to his love of throwing parties — Aynhoe Park has hosted Noel Gallagher’s 50th birthday party and scores of celebrity weddings. As we walk through the ample club space in the basement, he name-checks the likes of Peggy Gou as recent guests on the decks. He and his wife Sophie also host the backstage VIP area at Wilderness Festival, with a nod to Perkins’ roots. “We had a Fantazia Friday last year,” he explains. “The amount of memories that came flooding back. People tapped me on the shoulder saying, ‘I used to go to your parties!’ It was really nice to see there was a lot of warmth towards the music.”

Fantazia parties still take place, catering to a nostalgic rave throwback crowd, but Perkins has a less hands-on approach, with the brand licensed out to various promoters — with mixed results. There was a run of successful events in Glasgow at spaces like the Braehead Arena, handled by Colours promoter Ricky McGowan. Joe Peng talked positively about a Fantazia show in Australia in 2017 with Ratpack and 2 Bad Mice.

But in 2018, the Fantazia brand was attached to Another World festival, organised by Lee Barnard. The debut event seemingly appeared out of nowhere with a heavyweight line-up across more than nine stages, and was mired by last minute site changes before finally being cancelled, with the spurious excuse of sheep faeces in the fields causing a health and safety risk.

As of November 2019, disgruntled ticket holders were still seeking refunds despite Another World Festivals Ltd still being registered as an active business. “I didn’t have anything to do with Another World,” Perkins asserts. “We had licensed the Fantazia name out, but withdrew on the arrangement when it became clear they weren’t going to be able to deliver on what they were promising.”

LEGACY

Fantazia didn’t take place in a vacuum — they were one of a few significant promoters that broke rave culture to a huge audience. The format of these events foreshadowed the booming festival landscape, especially in the UK. Although there’s a fondness for the anarchy of the free parties, most people DJ Mag spoke to for this piece agreed that the benefits of licensed events far outweighed the drawbacks.

“We were just more accessible,” says Perkins. “I believe we were far cooler because we actually spent money on the production because we weren't worried about it getting seized by the police. The ethos of Fantazia was the person that bought the ticket is my boss. And I wanted to give them an experience they’d never forget.”

“People like to rebel and I loved free parties, but the free ones ain’t got nothing on the Fantazias and Universes, have they?” argues Joe Peng. “You haven’t got the fairground rides, you haven’t got the people from all over the place that wouldn’t go to the free raves. That’s why it was so monumental, because it opened it up to young people that needed something.”

Some seasoned ravers on social media commented on Fantazia as a gateway event that drew them into the culture. One suggested that Universe (who went on to organise the Tribal Gathering festivals) catered to a more mature, experienced crowd and played more diverse sounds. But even with the criticisms around the Littlecote House New Year’s Eve event, the dominant consensus was that Fantazia set a standard of quality for the brief phenomenon of these huge, legal raves.

“They were a bunch of boys with a vision who made that vision happen,” adds Peng. “They were definitely coming from a good place. And there were definitely ones in different organisations that weren’t. You’d never get that sense with Fantazia — they always made you believe.”

You only need look to the now-viral video lifted from the end of the Littlecote House VHS release, which captures the scenes in the car park as pie-eyed partygoers process the night they’ve just had. “The wickedest time I have ever experienced at a rave,” says one refreshed customer. “Fantazia, number one. Never used to believe it, but Fantazia is number one.”