What ever happened to the chillout room?

Back in the day, every self-respecting club had a chillout room for those in need of some down time — an ambient space to lie down, kick back, roll one. But by the end of the ’90s, they had all-but disappeared. Here, Manu Ekanayake asks: where did they go? And what's the modern equivalent?

The ’90s were a boom time in dance music. Clubland’s main rooms were full of DJs going full-pelt towards rave Armageddon — something nascent superclub promoters were quick to realise they could make increasingly good money from. But something was left by the wayside as the decade moved on. Something you probably won’t have even seen in action unless you’re old enough to have been going clubbing back then. We’re talking about a place you could go for a break from the main room madness, where the music was more chilled: this could include anything from Brian Eno and classic soul to experimental jams from the '60s. There was room to sit down — you could probably even lie down if you wanted, there were often some beanbags for that. You could chat to your mates, roll one and have a smoke if you wanted too (but then again, you could do that pretty much anywhere) . Welcome to the chillout room everyone.

To try and understand why these spaces didn’t make it out of the ’90s en masse, DJ Mag approached four DJs from the more ambient end of the dance music spectrum. Three of them were partying and performing during the decade itself, while one is a relative newcomer still in their twenties, who gives us a sense of where things are headed. All have different experiences, but there’s also a lot of interesting overlaps too. We ask them what chillout rooms were like, why they were important, and what happened to them? Did the pre-1997 Tory government see them as an admission of drug use? Or was it Labour’s 2007 Smoking Ban that really finished them off? And finally, and perhaps most importantly: where does that leave us now?

“The chillout room was part of the club’s offering. They were there from the start of acid house, definitely from when we started going out properly in 1989 or so,” says Sally Rodgers from electronic duo A Man Called Adam. With 30 years and multiple albums under their belt, A Man Called Adam will be forever linked with Ibiza and the multi-genre Balearic beat movement pioneered by DJ Alfredo Fiorito and his contemporary from their early Amnesia days, Leo Mas. Nowadays Rodgers isn’t just a musician, she’s a part-time academic, too — as is long-time musical partner Steve Jones. Both of them have PhDs and lecture at universities Rodgers at Leeds Conservatoire and Jones at Teesside University) to subsidise their artistic endeavours, like music production, DJing (in Rodgers’ case) and sound design for art installations.

Rodgers makes a memorable appearance in Channel 4 documentary A Short Film About Chilling, which captured the seminal Ibiza 1990 clubbing tour. In that doc she talks about how A Man Called Adam only got on the trip because their rider demands were more reasonable than all the other acts. The following scene sees her absolutely belting out ‘Barefoot In The Head’ from the band’s 1991 debut LP ‘The Apple’ onstage at Ku nightclub, now known as Privilege. In short, she’s the perfect person to explain just what the ’90s chillout rooms were like.

A Man Called Adam would often find themselves booked for the chillout rooms of massive club brands of the day like Sheffield’s Gatecrasher, where the main room would play heavy-duty house, techno or trance. Drug consumption inside would be equally heavy and the risk of both overheating and just feeling a bit overwhelmed was real. So the welcoming chillout room, with its more mellow soundtrack and a few beanbags and lava lamps, became a necessity for many ravers. Sometimes though, the sublime turned to the ridiculous in the chillout space, and Rodgers has many anecdotes: “One party I remember vividly was up here in the North East. We played a place called the Redcar Bowl, which was a big rave with a full-pelt main room and then a chillout room. All was fine until one of the beanbag chairs split. So because people had Vicks VapoRub all over them (which, according to ’90s rave legend, was supposed to enhance the ecstasy rush) they were all sticky, so they were all covered in Styrofoam balls! The UV light was picking up the balls all night — it was fucking hilarious.”

But on a more serious note, she’s sure cost was a big factor in the chillout room’s decline. “I think a kind of compartmentalisation took place in promoters’ minds once acid house stopped being this big cultural movement and became a commercial entity,” she says. “The chillout room was always a place where people might come round with a big plate of fruit and free water, and that doesn’t work financially, so I think they just faded away for that reason.”

As we talk about the authorities’ concerns about drug use, this prompts another relevant memory: “We were doing a short tour of Hamburg and they had booths for drug-testing. The club would allow testing of your drugs so you know you’re not stuck with something shit. There was an openness about that which circumvented the idea that you weren’t admitting that there were drugs there. They were absolutely admitting that there were drugs there. But I don’t know what the legal situation is to do that here. I can imagine it in Holland.”

Rodgers touches on a hot topic. As the Guardian newspaper reported in June, the Home Office announced that festivals and those who test drugs at them, like the charity The Loop, will need a new licence to do so, at the cost of more than £3,000. These licences take more than three months to be issued and as such, 2023’s Parklife festival wasn’t able to offer testing of confiscated drugs for the first time since 2014, leaving clubbers unaware of potentially dangerous batches. Previously, an agreement with the local police was all that was needed for this potentially life-saving service.

DJ Mag catches up with Chris Coco over Zoom just after he gets back from DJing in Ibiza, a place vital to his own journey towards chillout music. His DJ pedigree goes back to the acid house era, when he was a resident at The Zap, a beachfront nightclub in Brighton, running the Coco Club Saturday nights from the late ’80s right through to the mid-’90s. He also released records as Coco Steel & Lovebomb with friends Lene Stokes and Craig Woodrow, but it was a life-changing sunset encounter at Ibiza’s Café Del Mar — not yet as well-known for its chillout compilations as it was for its stunning views — that caused his DJ sets to drop a few BPM, and he began to specialise in chillout sounds instead. In the early ’00s he took to the airwaves with Bestival co-founder Rob da Bank on BBC Radio 1. The Blue Room, an early hours weekend show, allowed them to play their weirdest records to a receptively relaxed audience.

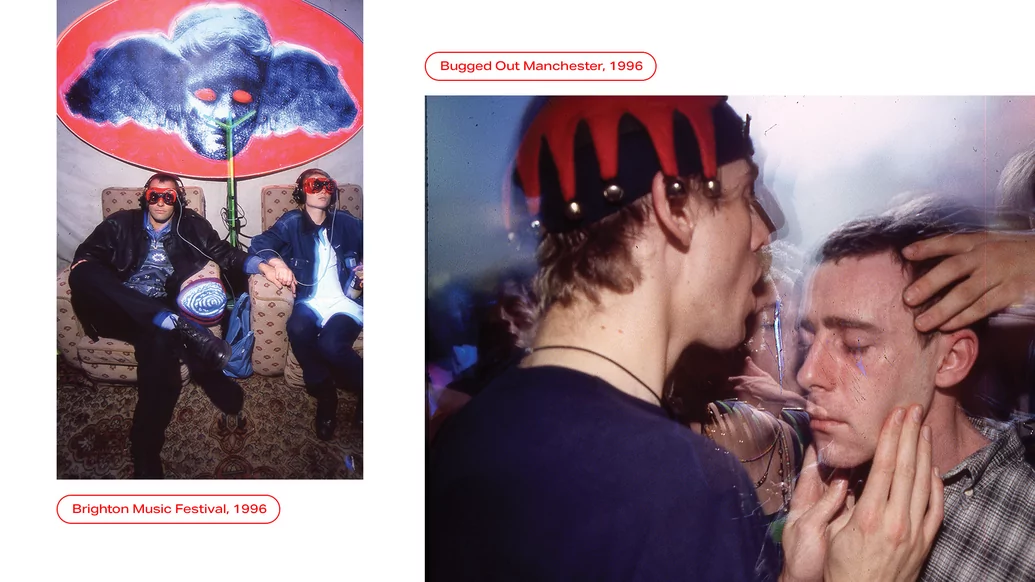

Nowadays, Coco remains a Café Del Mar mainstay while playing other sunset gigs around the world. His recent work with The Chill Out Tent, which has gone from a pandemic-based virtual event to a real one, shows he’s still got chilled vibes to spare. DJ Mag had to ask: what was his first experience of a chillout room like? “I think the first one I saw was actually at [early acid house party] Land Of Oz, which was run by Alex Paterson from The Orb. It was in that little room upstairs in Heaven. They were playing the weird music that turned into the KLF ‘Chill Out’ album.”

Released in 1990, this album gave the burgeoning chillout genre its name. Charting an imaginary night-time journey across the US going from Texas to Louisiana, it’s a mixture of samples, trippy melodies, spoken-word and snatches of music from Elvis to 808 State. And it still sounds pretty out there today, quite frankly. Released with its own tongue-in-cheek ‘ambient house manifesto’, it very much set the tone for the genre as a whole. As dance music evolved though, Coco felt things were becoming more formulaic, and as such, he saw a need for an alternative. “The point of a dance record is to make people dance. It’s functional,” he explains. “So there’s a lot you can’t explore in that world, as you can’t have 10 minutes where nothing happens — you need a breakdown or something.”

Coco doesn’t think that the chillout rooms were particularly seen as being druggy by the authorities — “you will need to sit down at some point, if you’re on drugs or not” — but he does think the 2007 Smoking Ban probably did move chillout room activities outdoors. He also puts things down to simple arithmetic. “I think promoters were looking at it and saying: ‘Why not have another full-on room here? Because if they keep dancing they’ll buy more drinks and we can pack more people in as everyone’s not just sitting down’. So I think that’s why they became less popular. I don’t think it was down to a lack of interest, I think it was more to do with the idea of packing people in as dance music got more ‘professional’.”

As to where the chilled scene is going now, Coco sees venues like Ibiza’s Café Del Mar as the true stalwarts, maintaining the original ethos. “That sunset thing still works. It’s a beautiful moment and it changes people’s views of the music and of the world. I also just played at Pikes on Sunday, which is a lovely thing. I played some slow house music, some old and some new. And one thing that’s become bigger more recently is the Japanese concept of ‘audiophile’ listening bars with incredible sound systems, places like Brilliant Corners and Spiritland in London. Those are ideal for what we do.”

Another DJ who mentions the freedom that comes with playing in audiophile bars is Dylan Yanez, AKA DF Tram. “I played at Spiritland last summer and those places are really good for being able to play whatever you want and knowing you have a great sound system to work with,” he tells DJ Mag. “It’s sort of like a chillout room because DJs can play the kind of music that you don’t usually play in clubs, but it’s not super loud so people can still eat and drink. I did a whole tribute to Vangelis for three hours — no club would let me do that!”

These days, Yanez is based in Austria, having left San Francisco, his home of over 20 years, in 2018. He’s from LA originally, but tells us that it wasn’t until moving to the Bay Area in the mid-’90s that he discovered club chillout rooms. There, he found he could play out ambient records he’d previously only listened to at home, and by the late ’90s his own Monday night party, Tranquility Base, was hosting the likes of UK chillout originator Mixmaster Morris until 2AM, before having to get up early for his day job.

It was also around this time that Tram first started working with visuals as well as audio, something he still does for his younger audiences. “I think the main reason chillout rooms aren’t around anymore is the fact that the Internet — and especially social media — have made younger people have shorter attention spans, so they can’t sit down and chillout for too long. They’re so inundated with media that I feel like a chillout room doesn’t offer a lot to them. This is why I wanted to do visuals too, to give kids another thing to experience.”

DJ Mag catches up with Sybil, a techno DJ with an ambient-leaning side, on her way to Portugal’s Waking Life Festival through London. Sybil feeds her love of ambient sounds via her Deep Mind Music mix series, as well as by playing the odd ambient gig — “When I can, but there are not that many opportunities. It’s not a money-maker [for promoters] so there’s not many chances.” Her experience of chillout rooms is different to the other artists we speak to as, being in her late twenties, the ’90s were before her time. Instead, she came to the music as a listener, citing her 2017 experience at Sweden’s Norberg Festival as the first time she heard “music you’d sink into rather than dance to” on a festival-size sound system. This was drone music, which remains her passion to this day.

Despite being a fairly recent convert, Sybil definitely sees the importance of chillout rooms. “Giving people a contrast to the dance space, I think this is something that ’90s parties understood and that clubs in Berlin still do,” she tells us. It’s hardly surprising that a young techno DJ sees Berlin as a more holistic clubbing locale, especially one who’s come up through a London scene beset by club closures, aggressive developers and unsympathetic local governments. “You need seating and that feels like something that clubs in the UK forgot about,” she continues. “It’s very difficult to party all night if you have nowhere to sit down. Then obviously a chillout space where you can already get further lost in music, but not having to dance while you do that, or having a chat with your friends — it adds a sustainable energy to a party.”

The reality of modern clubbing can leave little space for the chillout experience, as Sybil found out in 2018. In November that year, London promoters Percolate and Make Me decided to host a chillout room alongside their main room offering of Objekt B2B Call Super. “They had completely decked out E1 in East London with cushions and lights and mattresses on the floor,” Sybil explains, “but half-way through my set a bunch of security men said we had to stop the music. I asked them what was going on and they said, ‘It’s too dangerous, we can’t have people lying on the floor’. They stopped an ambient set for being too dangerous! I managed to carry on playing but they moved everyone out, so people’s beers spilled all over the floor and it was terrible, really. Talking to people afterwards it seems like the manager of E1 hadn’t fully understood what he signed off on.”

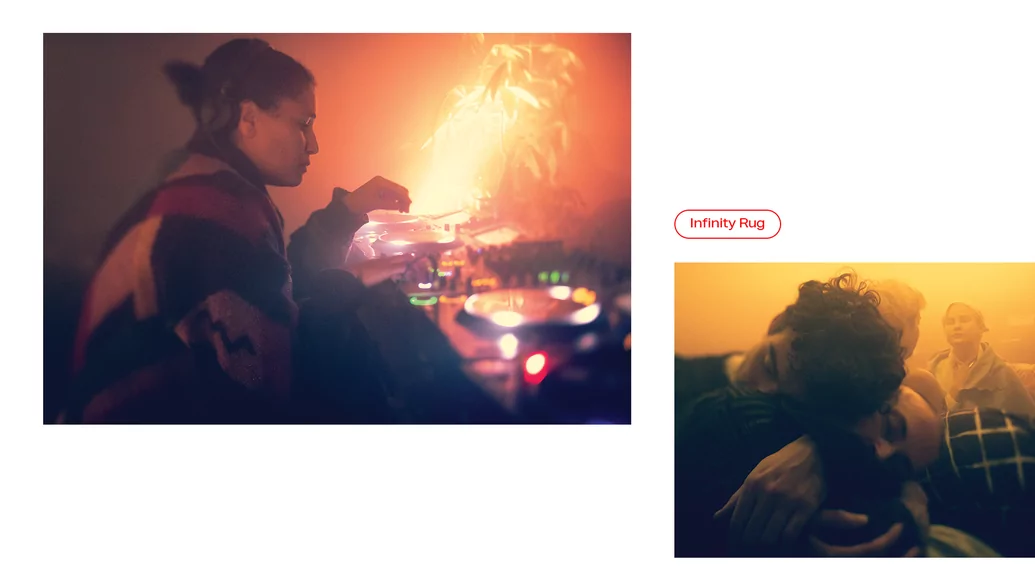

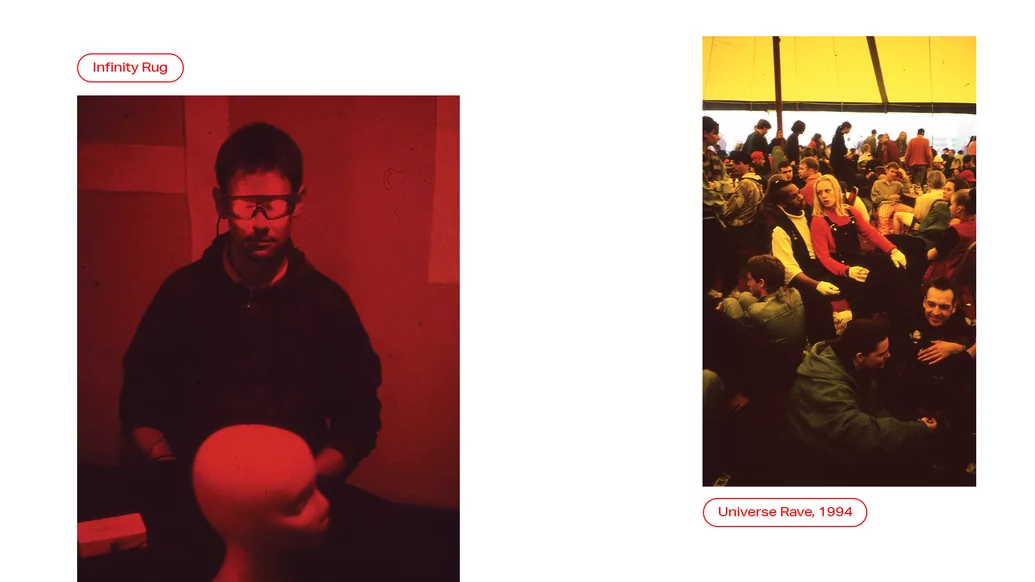

Sybil thinks that the future lies in looking at what festivals provide and learning from that offering, as well as from looking away from the UK for a future for chillout spaces. “Festivals already have people in a flow-state [what we casually describe as ‘in the zone’] so they can have a chillout space as an extra part of their offering. I play ambient sets at festivals, occasionally at clubs, but far less often.” She cites her regular gigs with Berlin and Lisbon party infinity rug as an example of the latter. Launched in 2021, promoters describe infinity rug as a “sonic seance” party where attendees may bring their own rug to lie on while they enjoy experimental music, poetry and food.

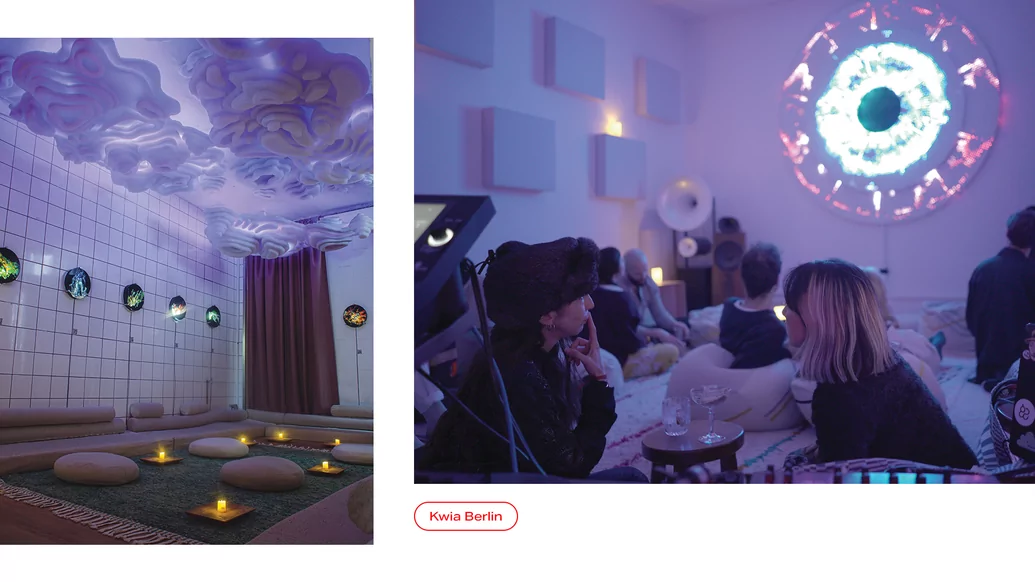

Days later, Sybil emails DJ Mag about another Berlin space: kwia. “I haven’t been yet but it’s a fairly new ambient/chillout bar,” she writes. “What I think is exciting about kwia is that it is not a listening bar in the sense of Brilliant Corners, etc., but it’s intended as a proper chillout room. People have to take their shoes off, there’s lots of sofas, and the soundtrack is ambient and chillout adjacent.

“There is a whole new scene around ambient these days, based around record labels like 3XL, Motion Ward, West Mineral and Appendix. Files. And artists like Special Guest DJ, exael, ben bondy, perila, ulla, nueen, nexciya, mu tate and Pontiac Streator. It’s all very online, for the most part; based around different mix series on SoundCloud and Bandcamp-only releases. But I see events popping up at kwia fairly often with a lot of these artists. They are at the heart of a new wave of ambient happening now which a lot of people of my generation are engaged in.”

So DJ Mag has to speak to kwia’s promoters, Arnold van Opstal and Barbara Rühling, who are just recovering from another busy weekend in Berlin. In the audiophile tradition, they host events in a professionally sound-treated venue with a hi-fi system that prizes “detail over power”. kwia, they tell us, is a place for “pure relaxation and immersion”, where guests can melt into the 1970s futurist decor.

“It’s quite funny that everyone expects us to play drone or Eno on repeat,” they say, explaining that what they’re really trying to do is give some emphasis to music heard less often in clubs: they’re as much about dub, shoegaze and dream pop as they are IDM and deconstructed club music. Basically anything the DJ wants to play goes, in an environment they consider more of a chillout room rather than a traditional listening bar.

But what about the artists Sybil mentions? Well, now this is where kwia’s all-important community aspect comes into play. The promoters laud the way that the artists and listeners are often one and the same, showing that this is indeed a hub for a new scene. “These artists are part of the space and they represent everything we love in music: creating platforms for others, not gatekeeping but collaborating between all levels of experience, and being welcoming to others. They represent the ideals of kwia itself.”

Idealistic words indeed, but that seems like the right note to end on. Because while the ’90s chillout rooms may be long gone, it looks like the spirit of that scene lives on in a new generation of clubbers looking to get away from the main room madness. Long may they chill.