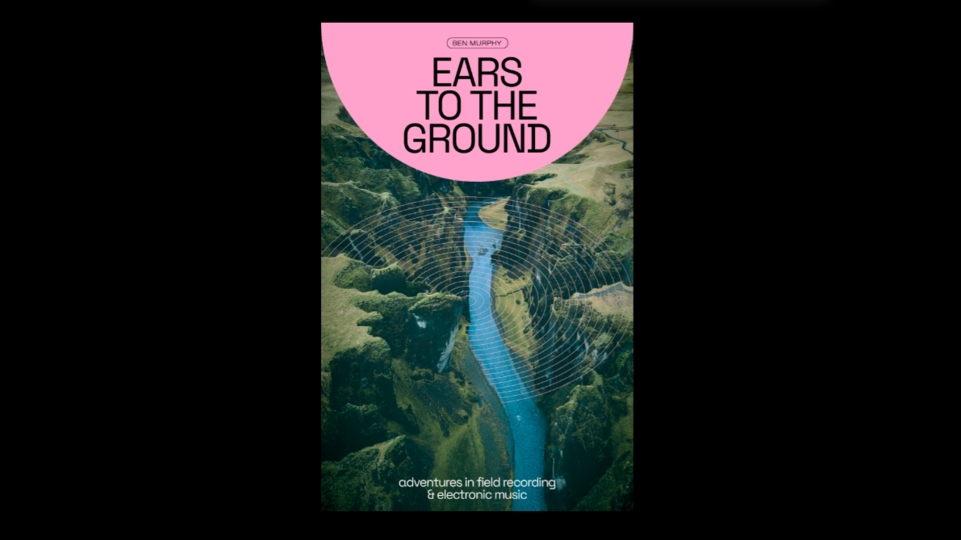

Ears To The Ground: Dance music, found sounds, and cultural heritage

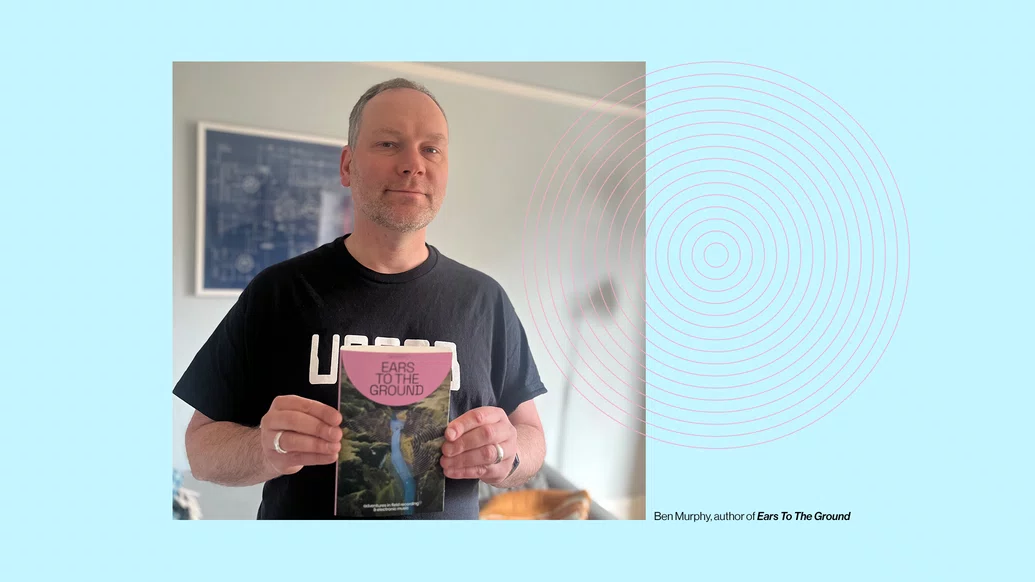

In this excerpt from Ears To The Ground: Adventures in Field Recording and Electronic Music, author and DJ Mag contributing editor Ben Murphy explores the use of found sounds in dance music as a means of examining and expressing cultural heritage in our surroundings

At its most cutting edge, dance music is a laboratory of sonic experimentation. Field recordings, foley and samples from the real world have long been part of the production palette for the most forward-thinking artists. When it comes to the use of found sounds, South London producer Burial is a genius. William Bevan’s dark, mournful twist on UK garage emerged from the underground in 2005, and his self-titled debut album the following year crossed over and resonated way beyond the dance world.

Atmospheric and cavernous, his sound evoked the feeling of rain streaked south London streets viewed through the fogged windows of a night bus in the early hours, but it was 2007’s ‘Untrue’ that was his masterpiece. On album tracks like ‘Near Dark’, the sounds of thunder, rain, and the crackle of radio interference merge with foley sounds of spent bullet shells hitting a concrete floor, sampled from a Playstation game. ‘Etched Headplate’ uses the sound of a cigarette lighter being sparked for its skippy snare sound: both an evocation of late night smoking sessions, and a reference to the offbeat drum hits of the jungle / drum & bass rhythms that first inspired him.

The found sounds that Burial uses serve to enhance the atmosphere of his tracks, but they also cloak their deep emotions. Often melancholic, sometimes euphoric, the sense of fuzz, crackle and rain in his music, and the sonically-altered R&B voices – sampled from YouTube cover version acapellas – are submerged, lending the best of his music a surreal, dreamlike quality. In his famous Wire interview with late writer and theorist Mark Fisher, Burial said: “If you hide sounds in the mist, it’s like a veil across the far wall of the tune”.

On his second album ‘Let’s Get Killed’, Belfast DJ, producer and film soundtrack composer David Holmes documented a wild trip around New York, interspersing the beats with snippets of conversation with people on the street, and ambient noise recorded around the city. The recordings were made when Holmes visited NYC when he was 17, but he didn’t use them until ten years later. The resulting album showed his cinematic flair, its extreme tales bringing the Big Apple to life, and its variety of styles, from drum & bass to trip-hop, showing Holmes’ consummate skill as a producer.

Today, field recording is an international art, and a fresh faction of dance producers is using them in unconventional ways. Producers in Morocco, Egypt, Tanzania, Uganda, China, Japan, Jamaica, Colombia and Argentina have incorporated found sounds into club-compatible tracks, which also communicate their environments and express their cultural heritage.

Morocco’s Guedra Guedra (real name Abdellah M Hassak) takes his artist moniker from the folk dance of the same name. Guedra also refers to a cooking pot, which can be adapted into a drum when a leather skin is stretched over the top of it. Hassak mixes samples of both Moroccan folk music and music from countries south of the Sahara, from chants to instrumentation and percussion, with atmospheric recordings and dance beats that draw from bass-led genres such as dubstep, footwork and jungle. On his 2021 album ‘Vexilology’, the electronic and organic rhythms merge to the extent that you can’t hear the join. The track ‘Aura’ samples the chanting of the Zayane mountain community, and positions it over wubbing sub-bass; on other tracks, traditional instruments such as the taghanimt flute and bendir drum are used.

“The Guedra Guedra project was first created following a desire to propose another way of imagining and producing music inspired by my culture and my history,” he told Mixmag. Talking of the way in which he harmoniously combines his recordings with electronic beats, he said: “I never think of giving a specific style to a specific production, the first important element is to produce some new stuff that exactly matches the true reality of African field recordings and archive without distorting it to keep the true poetic sense. I think it’s this crossing that gives that final touch to this music, there will always be different results from one song to another.”

Though his work focuses on representing different folk traditions through an electronic music lens, Guedra Guedra is also thrilled by the musicality of the world itself. On his album’s first track, ‘Seven Poets’, the trill of a songbird is threaded through musical chants, and looped in a rhythmic way so as to become almost a percussive device. Talking to interview website 15 Questions, he spoke of how field recording devices, and the way they capture sound, allows us to hear the world anew.

“Nature itself can be considered a vast ‘musical composition’ to be harmonised by highlighting natural sounds,’ he said. “The most moving experiences I’ve had with these non-human created sounds have primarily occurred when I’ve listened to the world through various sound-capturing tools, such as acoustic microphones, hydrophones, electromagnetic sensors, binaural and mono recordings, and more.

“These tools have allowed me to perceive the world in ways different from those perceived by the human ear alone. By listening to the world with these devices, I’ve been captivated by sounds I could never have grasped otherwise. Birdsong, rustling leaves, ocean waves – all these sounds take on a new dimension, revealing a hidden symphony woven into the fabric of nature itself.

“I consider these experiences ‘musical’ in the sense that they present elements of composition and structure that evoke emotions similar to those of traditional music,” he continued. “The rhythmic patterns, natural melodies, and complex sonic textures found in these non-human sounds create an organic harmony that resonates with our senses in a profound and powerful way.”

If Guedra Guedra uses field recordings to make explicit links between the organic and electronic, between traditional sounds and newer dance genres, then the band Nihiloxica, based between Uganda and the UK, use them in quite a different way: as a form of protest. The band were denied entry into the UK when attempting to tour there in 2022, and turned the experience into the livid electronics, midway between heavy metal and techno, of their album ‘Source of Denial’.

The title track is a distorted burst of synth noise and a fusil- lade of heavy drums, with a melody that emerges like the heaviest of sludge metal riffs. Peppered through the album are samples of their frustrated efforts to get a work visa for the UK, with automated phone responses from the UK immigration service, such as disembodied English accented voices asking if the caller “has been involved in crimes against humanity” and other insulting questions, while the final track is just an engaged tone, ringing on and on in perpetuity until it’s overtaken by distortion.

“We wanted to create the sense of being in the endless, bureaucratic hell-hole of attempting to travel to a foreign country that deems itself superior to where you’re from,’ the band has said. “We’re focusing on the UK as that’s where we’ve had the most trouble, but the problem goes much, much further. In this system, if you have a certain passport or have even visited a certain country, then you’re an appropriate subject to be interrogated and insulted time and time again just to prove that you’re worthy to enter, and normally this involves proving you have a good enough reason to want to leave again! The arrogance of it is unbearable. This album was a way to express our disdain towards it... what exactly is the source of your denial? Your passport? Your bank balance? Your skin colour? You’ve paid huge sums of money to be thrown from one profit-driven ‘service centre’ to another, each denying responsibility, each limiting your right to freedom of movement as a human being. Despite some other serious humanitarian short-comings, Uganda accepts some of the highest numbers of refugees in the world. Meanwhile, the UK is trying to send them away to Rwanda. That says it all.”

Like Guedra Guedra, the music that Nihiloxica makes celebrates cultural heritage. The percussive aspect of their sound derives from Bugandan drumming, a traditional Ugandan form. Nihiloxica formed around the nucleus of Nyege Nyege Studio in Uganda’s capital Kampala, releasing their debut EP on the studio’s world-renowned Nyege Nyege Tapes label. The label has become a platform for some of the most adventurous and original new music on the continent, with some of the artists also experimenting with field recordings.

Duke, a DJ and producer from Dar Es Salaam in Tanzania, works within the underground singeli genre, known for its hyper speed BPMs and kinetic energy. On his 2019 album, ‘Uingizaji Hewa’, crowd-hyping raps mix with advertising jingles from Tanzanian radio, speedy beats and circuitous synth riffs, plus ambient found sounds he recorded around his studio. It’s a unique sound, drawing influences from hip-hop and club music, but possessed of a left-field experimentalism.

In Cairo, Egypt, ZULI (real name Ahmed El Ghazoly) has drawn a lot of attention for his genre-defying dance tracks and eerie electronica. On his album for Lee Gamble’s UIQ label, 2018’s ‘Terminal’, he mixed trap beats with drifting ambient tones, glitchy rhythms, the raps of MCs like Abyusif and grime samples, before heading into the kind of melancholy synth work you can imagine Actress making on tracks like ‘Stacks & Arrays’, while his more club driven EP ‘All Caps’ taps into jungle and breakcore.

Especially enthralling is 2020 cassette ‘One’, released on Boomkat. Here, the barking of dogs, radio interference, traffic noise, conversations and the hubbub of street sounds issuing through an open window thread through tunes that chop up hip-hop break-beats, jungle, Egyptian pop and unearthly synthscapes. The second side of the tape literally records the ambient sounds of ZULI’s bedroom studio, complete with the meta noises of him tapping away at his computer, producing the pieces that comprise the release.

Explaining the creation of this lockdown derived cassette, he said on the Boomkat website: “Both sides are collages of original music, field recordings and improvised, single-take jam sessions with field samples of everyday Cairo-cacophony under curfew. For side B I placed a field recorder by the window of my studio while jamming, so that the music and street sounds were recorded simultaneously. The music on this side isn’t entirely in the spotlight, but rather part of the environment.”

Field recordings are an integral part of the music created by Yu Su. Born and raised in Kaifeng, China, she moved to Vancouver, Canada in 2013, and has a sound somewhere between ambient music, electronica, house and dub. Her album ‘Yellow River Blue’ was inspired by a tour across China from Qingdao to Xining, with tracks like “Melaleuca” marked by their disco basslines, propulsive kick drums and lush melodies. Through the record, atmospheric recordings lend a patina of organic life to the tranquil electronics. Yu Su uses both recordings she has gathered herself and samples from the internet, drawing from nature and cultural life alike to create her compositions. Discussing a sample pack she created for the website Splice, Yu Su said: ‘I mainly use microphones to capture field recordings, and then turn them into instruments that I can use (either melodic or percussive). Otherwise, I just modify presets on my synths.

‘I’ve done a couple field recording-based research projects, and have a collection of soundscapes that I’ve made over the past couple years,’ she added. ‘It’s just nice to have them around for listening every once in a while, even if I don’t use them in my music. I of course search for sounds I like on the internet as well – I’ve found some amazing recordings of old villages in Southwest China, and I don’t think I could have ever come across them without the internet.’

In Jamaica, dancehall collective Equinknoxx use field recordings to decorate their experimental club-geared rhythms. Though production duo Gavin Blair and Jordan Chung may have started out crafting beats for dancehall vocalists like Beenie Man and Busy Signal, their own material is more abstract. On the exceptional Colón Man album, hawk cries mix with running taps, lush pads, electrical interference and thumping kicks, cut up synth samples and percussive sounds derived from field recordings made on a Zoom recorder. “I have been convinced in the past to put a recorder on a ladder and put the ladder up a tree,” Blair told FACT in 2017. For him, field recordings are a way to interpret the world; they’re also sonic time capsules, capturing a moment that later generations can listen to and travel back to a particular place and time.

“We live in an age where we’re able to do these things and it’s important that if the average man feels like he wants to capture this thing just to be a part of his soul or even to shape the world, it’s important that this person is able to do it – even for future generations to have these things for reference,’ Blair said in the same article. “What a particular street in Jamaica sounds like now might sound different in the next 10 years and the man that recorded that just for his own fulfil- ment or joy... they might even end up in the national library one day.”

There is of course considerable precedent to this experimental use of atmosphere and found sound in Jamaican music. The late Lee “Scratch” Perry was renowned for his innovative studio desk manipulations, also using samples of cows mooing, thunderclaps and babies crying to add another mystical layer to his production, while another genius of dub, Joe Gibbs, liked to add snippets of racing cars and running water to his versions. Equiknoxx acknowledge this history: in an interview with the Carhartt website, Blair said: “Coming from a culture with traditions in dub techniques, longform dub poetry, Nyabinghi and Kumina... ambience, time and space feel like second nature”.

These artists, each in their own way, show the breadth of possibilities that field recordings have. Far from the pristine academic nature of some sound art, they’ve used these snapshots to add depth and texture to their rhythmic dance tracks, in the process commenting on their surroundings, and putting some of the real world into what can sometimes feel a little rigid. More importantly, they’re challenging the proposition that field recordings are a Western tradition, by making some of the most vital and original creations in existence.

Velocity Press will publish Ears To The Ground: Adventures in Field Recording and Electronic Music on 10th May. Pre-order it via the Velocity Press website.