Who owns the night?: the complicated reality of the Night-Time Economy

The relationship between dance music and British politics has often been fraught and confrontational. But in the last five years, promoters and politicians have started to break down barriers, uniting around the “Night-Time Economy”. Has dance music benefited from embracing the concept, or is an emphasis on financial growth and political optics bleeding the life out of clubbing? Ed Gillett speaks to Night Czars, venue owners and artists to find out

Ever since the late 1980s, UK dance music’s interactions with politicians, police officers and mainstream public opinion have been defined by suspicion, misunderstanding or outright hostility. From the Criminal Justice Act to tabloid headlines, licensing laws to police tactics, those in power have repeatedly treated our collective need to dance as something to be feared and controlled, rather than celebrated or supported.

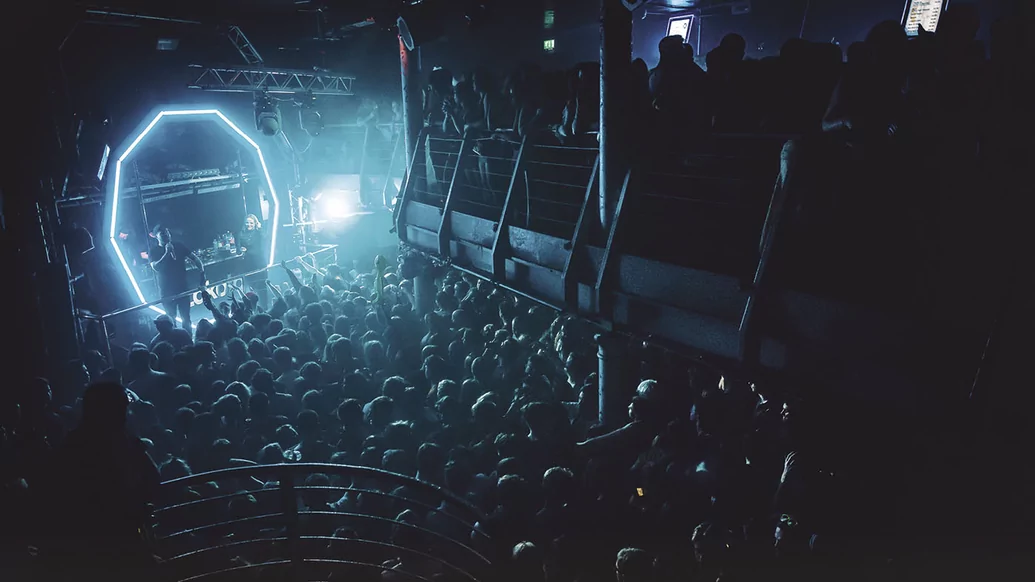

Slowly, though, things are changing. In the last five years, MPs have fallen over themselves to champion the Night-Time Economy — defined by the London Night Time Commission as anything taking place in the city between 6pm and 6am, affecting everyone from warehouse ravers to overnight carers. As part of this approach, public bodies at local and national level have recognised that late-night venues and workers deserve to be considered alongside the rest of the UK’s creative industries.

This shift can be traced back to New Labour, who came into power determined to position music and culture as essential parts of Britain’s economic and national branding. Music, theatre, art, even clubbing: these things don’t just matter because they make us feel good, Tony Blair and others told us, but because they employ people and spark investment. Recent conversations around the Night-Time Economy are an extension of that same ideology: an industry formerly dismissed as seedy and disreputable is now recognised as lucrative and culturally vital. By bringing nightlife into the political mainstream, politicians offer to make our late-night experiences bigger, better, safer and more successful.

In return, the dance music industry has shifted to meet these new priorities, refocus on economics rather than just culture, and make itself more palatable to mainstream political opinion. But this creates its own risks: of losing the radical, anti-establishment edge that makes dance music a creative force, and of shutting smaller venues and marginalised audiences out of the debate.

It feels like the right time to reassess what these trade-offs have meant for UK clubs: have we benefited from embracing the concept of the Night-Time Economy, or is an emphasis on financial growth and political optics bleeding the life out of dancefloors?

A critical starting point was Fabric’s closure in 2016, following an undercover police operation and the revocation of its license. Outrage focused not only on the closure itself, but the nakedly aggressive agendas behind it, like the Met Police naming their undercover sting Operation Lenor, a cheap pun on a brand of fabric softener, or Islington Council’s apparent disinterest in saving a venue it had lauded as industry-leading. If a club like Fabric could be bullied out of existence, what hope did anyone else have?

For London’s newly-elected Mayor Sadiq Khan, Fabric’s closure was a chance to live up to his manifesto pledges to support the Night-Time Economy. In November 2016, he appointed promoter, writer and DJ Amy Lamé as the UK’s first Night Czar. “The first thing Sadiq said to me when I started my role was, ‘You have to get Fabric reopened’,” Lamé tells us.

After five years in the job, it’s fair to say that Lamé still divides opinion, and has at times faced undeserved hostility. But she’s quick to defend her track record. “I’m proud that we were able to get Fabric reopened,” she says, “and to have helped stem the fall in numbers of grassroots music venues and LGBTQ+ venues, after years of decline. I was really proud to launch the Women’s Night Safety Charter, to work successfully with the Metropolitan Police to scrap Form 696, and to have created innovative ways of working with the police and music industry.”

Given the complex remit of Lamé’s role, these are sizable achievements, but they also reflect some of the limitations of Night-Time Economy thinking. Fabric’s reopening was important politically, financially, and symbolically, but the practical implications for other venues are less obvious: few, if any, would be able to mobilise hundreds of thousands of supporters to sign petitions, or crowdfund a quarter of a million pounds for legal fees, as Fabric did. Sadiq Khan’s decision to place Fabric at the top of the agenda is perhaps a reflection of the Night-Time Economy’s priorities: larger operators contribute more to that economy, so they inevitably occupy a more central place in discussions around it.

But public attention and political capital are finite resources: the energy spent on Fabric means less is available elsewhere. Similarly, Lamé is correct to note that the rate of venue closures in the capital has slowed or reversed, but information on which types of club are thriving or struggling is harder to come by. Anecdotally, it feels like many of the venues which have closed since Lamé’s appointment — like Ghost Notes, XXL or The Alibi — are noticeably different in scale, location or culture to the spaces replacing them, whether that’s Printworks, Glam Shoreditch or E1. A 2017 study into club closures across London revealed an increasing relocation of nightlife away from the centre of the city to its northern and eastern fringes: looking only at the overall numbers may risk missing these trends.

The closure of Southwark LGBTQ+ venue XXL in 2019 reflects similar themes. Here, the threat came not from licensing sub-committees but private developers building luxury flats, offices and a hotel, forcing out existing tenants in the process. In an interview with the Guardian, XXL co-owner James McNeil said: “It was the only LGBT bar or venue left in Southwark. It’s like we’ve been socially cleansed.”

Correspondence between City Hall and XXL, published under freedom of information legislation, makes for interesting reading, and suggests the limits of the Night-Time Economy’s influence. Lamé and her team take XXL’s plight seriously, and do their best to get the warring parties around the table, but unlike Fabric, this is not an area where political pressure has a decisive effect. Ultimately, her role isn’t designed to challenge global corporate demand for valuable London real estate. “We asked the Mayor’s office for help over two years ago and something should have been done then,” reads one email from McNeill, “before XXL becomes just another statistic.”

Complexity around issues of physical space, ownership and the relationship between landlords and tenants recur repeatedly within the Night-Time Economy. When Covid-19 hit the UK, the Night-Time Industries Association (NTIA) — the leading industry body for nightclubs and promoters, and one of the key voices pushing Night-Time Economy rhetoric up the political agenda — wrote to the government demanding urgent support for nightlife.

However, this wasn’t a call for direct funding for promoters, DJs or venue managers, but a mortgage holiday for venue owners, with the letter’s signatories made up primarily of property developers and corporate landlords. Those financial benefits would have trickled down to people on the frontlines, the NTIA argued, but their decision about whose voices and needs to prioritise feels telling: when cultural and business interests pull in different directions, the Night-Time Economy sometimes instinctively sides with the latter. (It has to be said, though, that since this the NTIA has done a lot of fine grassroots work during the pandemic).

Other structural limitations are visible with the 2018 decision by Hackney Council to effectively ban all new venues from opening past midnight. Amy Lamé’s response to the subsequent outrage — that her role has no control over licensing, so there’s nothing she could do — was factually correct but felt underwhelming, and was met with derision. If the Night Czar’s consolidation of soft power couldn’t prevent such an indiscriminate clampdown from such a key borough, people asked, then what was it for?

The difficulty of finding common ground between London’s competing cultural and political priorities are underlined when we speak to Dan Beaumont, owner of venues Dalston Superstore and Dance Tunnel, the latter until its closure in 2016, a decision Beaumont linked explicitly to the licensing climate in Hackney. “I’ve seen Amy work with the Culture At Risk team,” Beaumont says, “and there’s a lot of work going into protecting venues, growing their infrastructure and supporting start- ups, producing important data that demonstrates the importance of the sector. So I think with the powers available to her, I see a lot of good work being done.” For Beaumont, the problem isn’t with Lamé or her work as Night Czar, but the wider political context in which the Night-Time Economy sits.

“I do think nightlife has become more valued over the last five years, but there are still a lot of concerning barriers,” he says. “The whole structure around licenses is geared towards stopping bad things happening, when the reality is that licensed venues are generators of culture, and can be economically regenerative. None of these big ideas can ever be reflected in licensing decisions, though — which come down to the minutiae of things like people pissing in doorways — because they can’t deviate from existing policies on economic, cultural, or social grounds.

“Council elections across London invariably have very low turnout,” continues Beaumont, “so you have local politicians, who get voted in by a very small number of local residents, making huge decisions about the cultural fabric of our cities. Councillors have a huge amount of discretionary power to make decisions about what they think is appropriate for their area, but the most politically engaged people at a local level are not necessarily the people you see on dancefloors.”

London’s problems are complicated by the fact that each of its 32 local authorities set their own licensing priorities and have, in Beaumont’s words, “largely pursued policies around trying to shift late-night activity away, so you have a real race to the bottom, with no pan-London policy on licensing”.

Or, as CEO of the Night-Time Industries Association, Michael Kill, put it, when speaking to DJ Mag for our May issue: “The government has a really long way to go in terms of grasping contemporary music culture. Given that the average age of a local councillor is somewhere between 60 and 65, there’s a lot of education that needs to be put in place.”

The formation of a Night Time Borough Champions Network, bringing together local authorities from across London to share good practice, is both a tacit acceptance that things aren’t as consistent as they should be, and an example of the Night-Time Economy working positively to address these shortcomings.

“There’s a huge gap between the people that are creating this culture, and the people saying ‘We are culture’" - Carly Heath, Night Time Economy Advisor for Bristol

Carly Heath, who was appointed Night Time Economy Advisor for Bristol in March 2021, agrees that this disconnect between dance music scenes and the people making political decisions about them is critically important. Influenced by her background in “venues you don’t wear your good shoes to”, as she puts it, she focuses on how these imbalances affect more marginalised communities. “There’s a huge gap between the people that are creating this culture, and the people saying ‘We are culture’,” she explains. “I think part of that’s because the nature of underground cultures is that they don’t necessarily want anybody turning up, they want their own space. We shouldn’t pretend that all music, all of those cultures, are for all people. But we need to protect them properly, and not create policies that inhibit them from being able to do what they do.

“That connectivity in Bristol is embedded into the fabric of the city,” she continues, “but whether those people are in decision-making places is a question that’s still open. With promoters, the ones that tend to come into Bristol come here as students, put on a night for their mates because they can’t get gigs elsewhere, and the next thing you know they’ve been here 10 years and they’re big promoters. That’s fantastic, but we need to make sure that they’re not bastardising the work that’s gone before. My priority is to unpick stuff like this.”

That conflict between large and small promoters crops up noticeably in Manchester. Sacha Lord, Heath and Lamé’s Mancunian counterpart, combines his formal role as the city’s pre-eminent political voice on nightlife issues with his informal position as its most powerful promoter, through his ownership of the Warehouse Project and Parklife. Indeed, the scale of his economic interest in Manchester’s Night-Time Economy meant that he was one of the main voices calling for the creation of a Manchester Night Czar, a year before he ended up getting the job himself.

Since his appointment, Lord has been extremely visible in media and political circles. Rather than Lamé’s internal focus on improving London’s decision-making, or Heath’s emphasis on excluded voices, Lord has banged the drum aggressively from his position at the top of the industry. His profile has helped win some notable victories, like convincing the Arts Council to expand the scope of last year’s Culture Recovery Fund to more fully cover clubs and nightlife venues, but it also raises questions about perspective and priorities.

When DJ Mag spoke to Lord a few weeks ago, alongside Michael Kill of the NTIA, we asked about larger promoters using exclusivity clauses to prevent DJs playing rival venues in the same city, effectively barring these artists from smaller venues for months at a time. What lobbying efforts have they undertaken to protect grassroots operators from being squeezed out by bigger competitors?

“People need to understand that if you’re spending a lot of money on a particular artist, you don’t want that artist playing in a venue in the same city the week before,” Lord said. “It doesn’t make any sense. It’s like: I used to sell leather jackets on a market stall, so if I wanted to open a shop that sells leather jackets, okay, I’ll have my store, but I don’t want another leather jacket shop right next door to me. Fine if it’s around the corner, that’s no problem at all. So that’s all it is." Of course, this is a reasonable argument to make. But, just like the NTIA’s gravitation towards landlords and developers at the beginning of the pandemic, it suggests that Lord’s approach to these issues is invariably shaped by his own interests, connections and background. Even if subconsciously, the danger is that the Night-Time Economy ends up reflecting the needs of those who already have the biggest financial interests and the largest platforms.

Alternative visions of the Night-Time Economy do exist, though. One of Heath’s closest collaborators in Bristol is Marti Burgess. She’s owned the venue Lakota for 30-odd years, while also working as a lawyer, and has chaired the city’s Night-Time Panel, which helped establish the vital local networks and support systems which Heath is building on. “The whole thing is that politics has never been out of he dance music industry,” Burgess tells us.

“We opened Lakota in 1994, against the backdrop of the Criminal Justice Act, so we were fortunate in the sense that people weren’t able to go raving in fields or warehouses or under motorways. But it’s always been quite an adversarial relationship: we were one of the first venues in the UK to get a 24-hour license, but it was a real battle,” she says. “The police objected on the grounds that we were a place where children would get corrupted.”

Burgess sees problems of representation and mutual understanding within the political and legal system as comparable to those within the music industry. “As a Black British woman, both in my day job as a lawyer and owning a nightclub, neither of those spaces are friendly towards people of colour, particularly towards Black women,” she continues. “The funny and slightly dark thing is that I work in the legal industry, which is heavily regulated around discrimination, and I’d say it’s actually easier than music.”

Burgess agrees with Heath’s concerns that the benefits accruing from increased political engagement in dance music aren’t being distributed equally. “They’re not, because those who have access and knowledge and connections will always do better than the organisations which are struggling to survive, and aren’t part of the political or societal mainstream,” she says. And yet, as with any form of inequality, being able to name the problems in this way can start the process of dismantling them.

“One of the reasons I got involved with politics,” Burgess explains, “is because we’ve had to put up with so much strife from the local authority and the police. And I thought, ‘Yeah, I’m going to get involved in this, because it’s an opportunity for someone to really focus on these issues’.”

Parallels to Burgess’s experience can be found in the work of Belfast- based DJ Holly Lester. With licensing powers devolved from Westminster, Northern Ireland retains arguably the most draconian restrictions on dancing anywhere in Europe, with clubs unable to open past 3am and drinking banned after 1am.

When a recent review of licensing laws by the government failed to deal with the issue, Holly and others decided to form a campaign group called Free The Night. “The last time any of these rules were properly discussed was 25 years ago, and sadly the outcome of this recent amendment is just not the progressive approach we’d been hoping for,” Lester says. “What we’re asking for as Free The Night is that entertainment licenses can be extended by one hour, meaning that if venues choose to, we can keep drinking until 2am and dancing until 4am. We don’t think that’s a lot to ask for.”

What’s fascinating about Free The Night is that it’s being led by young dancers and DJs, not political operators. When Free The Night meets with Assembly members at Stormont to put their case forward, it’s Lester relating her own direct experiences as a DJ, not refracting those arguments through the priorities of others. “Almost everyone involved is under 30,” she explains.

“The pandemic has given creatives the space to find our voices politically, and some of the older generation of ravers in Northern Ireland are jaded, for want of a better word. The way politics works here is exhausting, and people here are really tired. I think that’s partly why it’s come together the way that it has.

“We’ve had really positive responses from every member of the Assembly that we’ve spoken to,” continues Lester. “What I want to see, in five years’ time, is that young people can live here and have all their creative, social and career needs met. This licensing part is the first step, but there are so many other issues that we want to target.” Lester’s approach is a bracing reminder that different approaches to the Night-Time Economy, which broaden and deepen the work already being done, remain entirely possible.

The work of Amy Lamé, Sacha Lord, the NTIA and others has successfully shifted the conversation away from viewing clubs as dens of iniquity, and towards a fuller recognition of their economic and cultural value. But club culture is fundamentally rooted in youth culture, and the cultures of communities excluded from the political mainstream: its vitality stems ultimately from those groups imagining and creating utopian alternatives to existing power structures, not replicating them. When we think about where these conversations might go next, perhaps the answer is for those on the front lines of dance music to seize this debate for ourselves, instead of outsourcing it to landlords, career politicians or baby boomers.