UK funky isn’t back — it never left

Over a decade since UK funky's initial peak, the growing popularity of percussive styles like gqom, kuduro and amapiano has sparked the interest of those who remember its mid-noughties heyday. As more and more artists begin to readopt the UK funky tag, some are declaring the sound as as ‘back’. But did it ever really leave? Or did it simply evolve? Sam Davies charts the genre’s history, and its enduring relevance to Afro-Caribbean music in the UK

Funky was that most intangible of British microscenes, built from a mesh of influences combining briefly to create something — a vibe, a beat — worthy of its own name. With catchy drum patterns placing emphasis on the offbeat, funky began in underground clubs and on pirate radio stations in the UK around 2006. From there, it tentatively entered mainstream culture, with a chart hit, a series of playground dance crazes, and even a few naff parodies on TV.

Yet funky’s mainstream lifespan was even shorter than grime and garage before it. As early as 2009 it was declared ‘over’, its peak so fleeting that some of its most vital figureheads now deny it ever really existed. (Funky’s originators initially christened the sound funky house, which stuck until someone pointed out that the name was already taken, by a ’90s house scene largely based on disco and funk samples.) Though it may feel like yesterday, funky nostalgia burns strongly enough that some have decreed a revival upon us.

Some of the last year’s most striking dance tracks bear the “UK funky” tag on Bandcamp, including records from DJ Plead, Logic 1000, Bamz, Tailor Jae & Traces, Hagan, Anz and Laksa. Clubland — both irl and url — has nurtured a growing fascination with rhythmic syncopation through scenes like gqom, kuduro, hard drum and amapiano. Released on labels like NAAFI, Gqom Oh! Príncipe, ETS, More Time and Nervous Horizon, these sounds have piqued the ears of those who danced to funky in its formative years. But is funky back? Or has it been with us ever since? To understand that properly, we need to trace its story from then to now.

“There’s been times when people’s booked me, and I’ve gone, and they’ve said ‘Oh, so you really exist!’” — Apple

It’s 2005: garage is out, grime is still breaking through, and dubstep hasn’t spread far beyond FWD>> and Plastic People yet. London needs a new sound it can dance to. That Boxing Day, a 20-year-old producer from Tottenham, North London fired up Fruity Loops on his new Sony Vaio. Inspired by hearing Bugz In The Attic play broken beat tunes at Soho’s Velvet Rooms, he programmed a simple snare beat and a four-note organ riff, looped it and called it ‘Dutty Dance’. As though pre-empting the Google age, he named himself Apple, an unsearchable moniker that would only compound his enigma.

“There’s been times when people’s booked me, and I’ve gone, and they’ve said ‘Oh, so you really exist!’” Apple says, sitting in a pub in North London. “I didn’t mean to be a ghost. That’s just how it happened.” He gave ‘Dutty Dance’ to Supa D, a friend with a regular slot DJing on Sundays at a club in Aldgate called Departure Lounge. Three weeks later the tune was getting rewound every time it dropped.

Apple felt enthused, and quickly made tracks ‘Mr Bean’ and ‘De Siegalizer’ (also variously known as ‘Segalizer’ and ‘Sieqaliser’), both as ridiculously simple and effective as ‘Dutty Dance’. “The scene at that time... Everyone was playing house,” Apple says. “Like a mixture of soulful, broken beats, but we didn't have our own identity, our own sounds.”

As well as house and broken beat, Apple grew up listening to his mum play Ghanaian highlife and his older cousins playing hardcore. He went to his first rave at 14, a jungle event called Telepathy MC’d by Stevie Hyper D. He also listened to rap — producers like Pete Rock, Alchemist, Premier — and started out making hip-hop beats of his own, including for Frisco, a childhood friend. “Thanks to Apple for supplying the beat,” raps Frisco on ‘God Blessed’, one of four Apple-produced cuts on the MC’s debut mixtape, ‘Back to Da Lab Vol. 1’.

In clubs like Supreme’s in Vauxhall and Turnmills in Farringdon, and on pirate stations like Rinse and Deja Vu, DJs like Supa, Marcus Nasty, MA-1, Kismet, Pioneer, Angie B, NG and Wigman started dropping ‘Siegalizer’ among the broken beat and house tracks of the time. Tunes like Wookie’s ‘Gallium’ and DJ Gregory’s ‘Attend’ were retroactively fitted with the funky tag, while similar instrumentals such as Roska’s ‘Feeline’ and Lil Silva’s ‘Seasons’ became staple selections.

“I get that a lot. People go, ‘You were the funky queen!’ and I’m like, ‘I so wasn’t’” — Kyla

Apple is now unequivocal about the scene’s genesis, however. “For the record I wanna say this: I was the first person to make... so to speak, that bullshit flipping ‘UK funky’, whatever they wanna call it. I was the first, man. I don’t wanna hear nothing else. I don’t wanna sound like I’m blowing my own trumpet, but I just wanna put that out there because I’ve seen people chat rubbish and say ‘Ah, that’s when the scene started’. No. The first tune was ‘Dutty Dance’.”

Next to grime and dubstep’s grit, this new sound was seen as a slight return to garage’s sheen of sophisticated fun. Club nights were given names like Red Carpet and punters dressed in shirts and heels. “It’s what all the girls want to go to,” said Wigman to RWD at the time. “It’s not a bunch of people standing about with moody faces, it’s people dancing and having a party.” Funky was bubbling; it just needed a star.

“I get that a lot,” says Kyla. “People go, ‘You were the funky queen!’ and I’m like, ‘I so wasn’t’.” Regardless, with her song ‘Do You Mind’, Kyla became the face of funky, an ersatz pop star. Born in Germany to a Jamaican dad and an American mum, Kyla and her family moved to Huntingdon, northwest of Cambridge, where she grew up listening to Motown and trying to sing like Mariah Carey. Her moment came after meeting a DJ and producer from North London called Paleface, who introduced Kyla to house music through Masters At Work, DJ Kent, Reel Soul and Kentphonik.

In 2007, Paleface and Kyla made ‘Do You Mind’, which many remember as being funky’s defining moment. Sort of. “Obviously ‘Do You Mind’ wasn't initially a funky tune,” Kyla says. “It was a bassline tune.” Paleface would rather be remembered for his contributions to bassline than for what he did in funky. Before answering the phone, he insists he’s not the right person to talk to about funky. “I literally only made about four tunes that came out,” he writes on WhatsApp.

The version of ‘Do You Mind’ people remember is a remix, produced by Paleface’s cousin Flukes under the name Crazy Cousinz (Paleface was once in Crazy Cousinz, along with two other producers, but Flukes is the only remaining member). Flukes used to watch hip-hop turntablist competitions on DMC World DJ Championships tapes as a kid. “One of the main reasons why I got into funky is because it had so much of a diverse sound,” he says, noting the presence of reggaeton, bashment, soca and broken beat in funky’s melting pot.

The Crazy Cousinz mix of ‘Do You Mind’ was officially released in 2008 and, for two years, funky was the sound of the summer. Vocals entered the mix, with tracks like Donae’o’s ‘Party Hard’, iLL BLU and Princess Nyah’s ‘Frontline’ and Crazy Cousinz’ ‘Bongo Jam’ emulating Kyla’s flirty singing style. It even began to spread beyond London, the scene’s pseudo-luxurious vibe a hit in Essex and a natural substitute for UK garage in Ayia Napa. DJs would mix pop tracks together using instrumentals by the likes of Apple, Geeneus, Scratcha DVA, Cooly G and Roska.

Funky was everywhere. Outsiders started looking in. As grime continued to flounder in the charts, Boy Better Know released the catchy ‘Too Many Man’ with a UK funky beat. One-hitters KIG dropped the briefly inescapable ‘Head, Shoulders, Kneez & Toez’. Grime rapper and P Money associate Funky Dee penned ‘Are You Gonna Bang Doe’, a crude pop hit built over ‘Chantes’, an Apple instrumental.

‘Are You Gonna Bang Doe’ got so big it was parodied by The Sun for a bingo ad, with the refrain changed to ‘Are You Gonna Bingo’. Apple never liked the tune, but has no hard feelings: he made more money off that track than anything else he ever produced (he hasn’t seen a penny from The Sun, though).

Funky’s shark-jump — its Bo Selecta moment — came in September 2009, with Gracious K’s ‘Migraine Skank’, another infectious bop which spawned dozens of copycat dance moves, or skanks. “I associate ‘UK funky’ with erm...” Apple chooses his words carefully. “I think it got big when people started doing all them flipping... dances. It started getting gimmicky, people doing all them vocals. And all them... skanks.”

“Funky got a big massive surge,” says Paleface. “Every Oceana was playing ‘Migraine Skank’. Everyone was playing the same standard tunes. I think when it gets to the same set of standard tunes, that’s when the scene crashes.”

And it did. Soon funky’s top proprietors moved on. Producers like Scratcha DVA and Cooly G were snapped up by Hyperdub for full-length albums. DJs and producers once reliant on funky moved on. Kyla and Paleface had a kid. Apple disappeared. Of its key players, only Roska truly stayed the course, consistently releasing records broadly classifiable as funky throughout the next decade.

Did funky die? “I think it’s been with us in an evolved guise,” says James from production duo iLL BLU. He and his production partner Darius effectively stopped releasing funky around 2012, after releasing records on Numbers and Hyperdub, but retained some of the sound’s DNA as they moved into working with rappers. James mentions MoStack’s ‘Murder’, which iLL BLU produced in 2016. “I remember turning to Darius when we were making it, ‘this feels like funky’, like the vibe we had when we were making tunes in our bedroom.”

iLL BLU have recently worked with drill artists like OFB, Unknown T and M24, notably with the latter two for the Vybz Kartel-sampling banger ‘Dumpa’. “Even on drill now you’re hearing more dancehall,” James reflects. “On ‘Dumpa’, we wanted to highlight that more.” He lists key pop moments like Major Lazer’s ‘Lean On’ and Drake’s ‘One Dance’ as proof that the rhythmic lineage, which began with dancehall and they say continued through funky, continues today. “It never really died: the genetics of the sound is in a lot of the music that we’re hearing now, just in a slightly different way.”

“[Uk funky has] led me to discover a lot of different types of music from around the world as well. It gave me a reference point” — Ahadadream

Drake’s first US Billboard number one was 2016’s ‘One Dance’, a sidestepping pop smash built around a sample of Crazy Cousinz’ ‘Do You Mind’ remix. Paleface remembers being in bed when his phone started ringing, eventually hearing Sony’s representatives play the song down the phone to him before the track was released the following Monday, going to number one in 15 countries.

Donae’o has stayed relevant with funky-ish collaborations like the collosal ‘Lock Doh’ with Giggs and the recent ‘I Wish You Loved You As Much As You Loved Him’ with The Streets. Jorja Smith has moved between garage and funky beats on hits like ‘On My Mind’, ‘Be Honest’ and ‘Come Over’. Jamaican music has always been a vital influence on British rap (see London Posse’s 1988 ragga rap hit ‘Money Mad’), but when ‘Too Many Man’ hit, it had an exciting, novel feel. Now, the proud embrace of Afro-Caribbean beats is commonplace, heard last year on tracks like Pa Salieu’s ‘Frontline’, Headie One’s ‘Mainstream’, Abra Cadabra’s ‘On Deck’ and Loski’s ‘Avengers’. Meanwhile Jamaican and diasporic artists like Popcaan have become household names in the UK

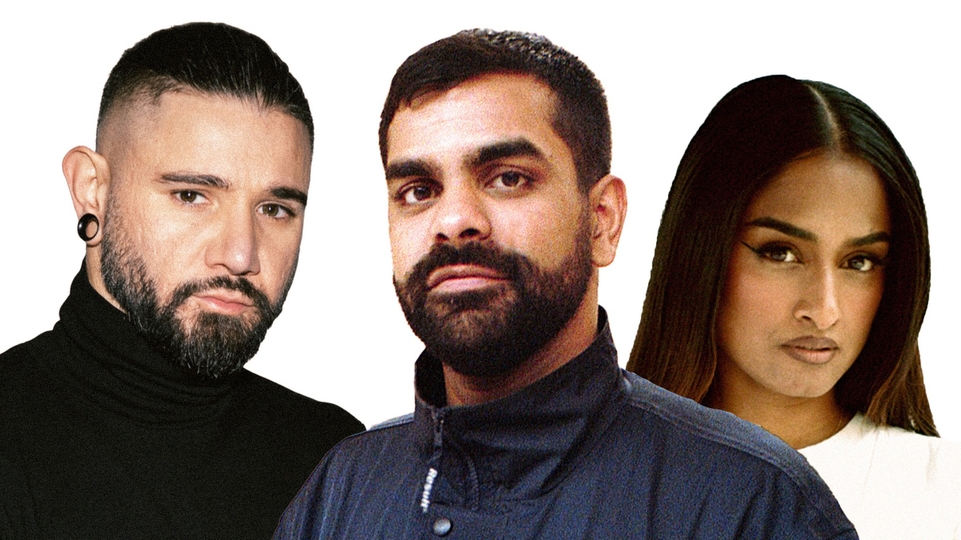

More Time Records, a label that’s been putting out rhythmic club records since 2017, was founded by Ahadadream and Sam Interface as a way of keeping the UK funky torch lit. Ahadadream remembers hearing Roska on BBC Radio 1’s Essential Mix when he was at university in 2011. “Since that — what, so nine years? — I’ve been consistently pushing that sound,” he says. Touchstone More Time releases like Mina and Bryte’s ‘Make Money’ and Interface’s ‘Yeke Yeke’ proudly bear the funky tag on Bandcamp. “It’s led me to discover a lot of different types of music from around the world as well. It gave me a reference point.”

Ahadadream, who has also hosted funky parties on Boiler Room and who previously held down a residency on the BBC Asian Network, talks about funky as a gateway genre for younger DJs today. “Although I would say I’m a UK funky DJ, because that was my first entry point to percussive club music, it led me onto things like gqom and kuduro... and the reason I like them is because they remind me of funky.”

He compares talk of a funky comeback with that of another, recently revived sound. “I think one of the reasons it hasn’t been able to gain the momentum of UK garage is because garage has got one name — it’s UK garage, but in our scene there’s like five, six, seven percussive club genres that get played,” says Ahadadream. Meshing under those genres are tracks like Off the Meds’ ‘Belter’ and LSDXOXO’s ‘Death Rattle’, releases on Príncipe and Hakuna Kulala played by DJs like Joy Orbison, Laurel Halo and Jamz Supernova. “You could put a blanket umbrella term on it that says ‘UK funky’, but that wouldn’t be accurate.”

Apple is more circumspect: “I would never say ‘UK funky’s back’... We’re on a different wave now.” He made his new ‘Bongoclart’ EP on that same Sony Vaio from 2005, this time inspired by a new sound. “The boys over South Africa, the amapiano producers... I’ve just got that feeling of 2006 again.”

Perhaps changing public attitudes have also contributed to a reappraisal of the funky sound, which was once heard with scepticism. “At one stage, Africans weren’t really proud to say where they were from, but now there’s pride there, more tapping into your culture through the rhythms, the slang, the content,” says James from iLL BLU. “I feel like Afro-Caribbean music is here to stay. It’s a big part of being a Black person in Britain — and even if you're not Black, you’ve now grown up with at least five, six years of UK artists that make Afro-Caribbean music being in the forefront: on TV, winning awards, in the charts. From whatever walk of life, if you’ve grown up in the UK, that’s our sound now.”