Seeing sound: The audio-visual artists driving creative innovation in club culture

Audio-visual artists have always played a vital role in shaping the distinctive aesthetic identity of electronic music. In the evolution of analogue slide projectors to real-time optical light shows and machine-learning animations, technological progress has opened up boundless opportunities for visual innovation in club culture. From the visionary pioneers to the next generation of grassroots creatives, DJ Mag shines a light on some the artists in the game today: the animators, film directors, live AVs, and everything in between

Adam Smith & Marcus Lyall are the London based creative duo behind The Chemical Brothers’ live shows and music videos, combining digital methods with real-life performers to build unique theatrical narratives.

“It’s almost like taking play very seriously,” says Lyall, nodding to The Chemical Brothers’ giant on-stage robots and the Japanese sci-fi influences in the 2019 Eve of Destruction video. “What makes the shows is the use of performers,” says Smith. “You haven't got a lead singer or front man necessarily, so having some other human connection through the visuals has been something very important.”

Although the pandemic led to a domino of cancellations for The Chemical Brothers tour in 2020, the duo were able to see some of their work displayed at the Design Museum’s Electronic exhibition. “Because of where we’re at, it became a very significant moment and quite emotional,” says Smith, explaining that a lot of the archived material on display formed part of their own history. “You don't quite realise the significance of it when it's happening,” says Lyall. “And then suddenly you find yourself in a museum and being part of something that is celebrated.”

“Now we use the lighting like a piece of animation and insert visuals to interact with the lights,” says Smith. “It's a very different thing from three slide projectors and a couple of strobe lights, which is what the first Chemical Brothers gig was.”

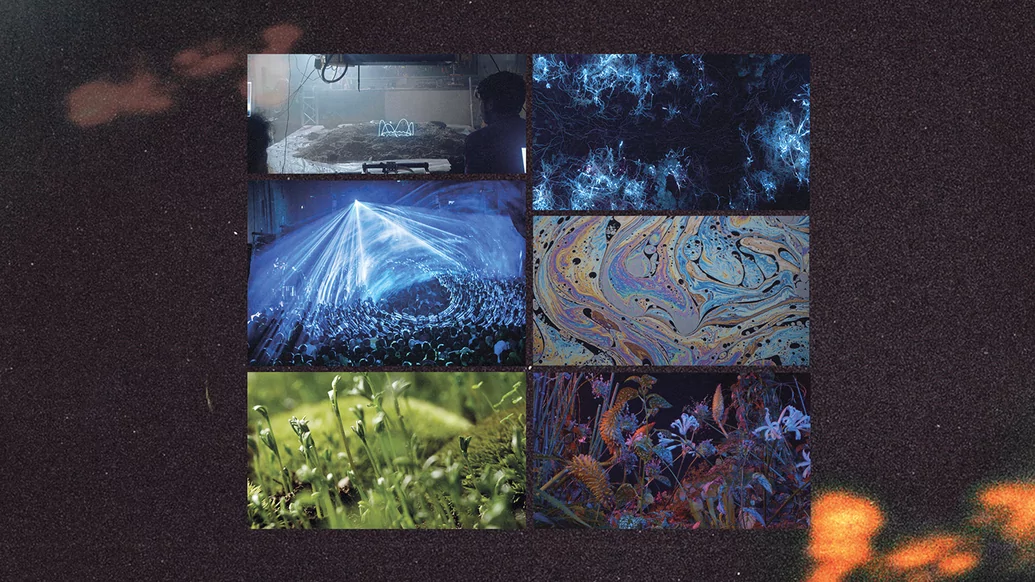

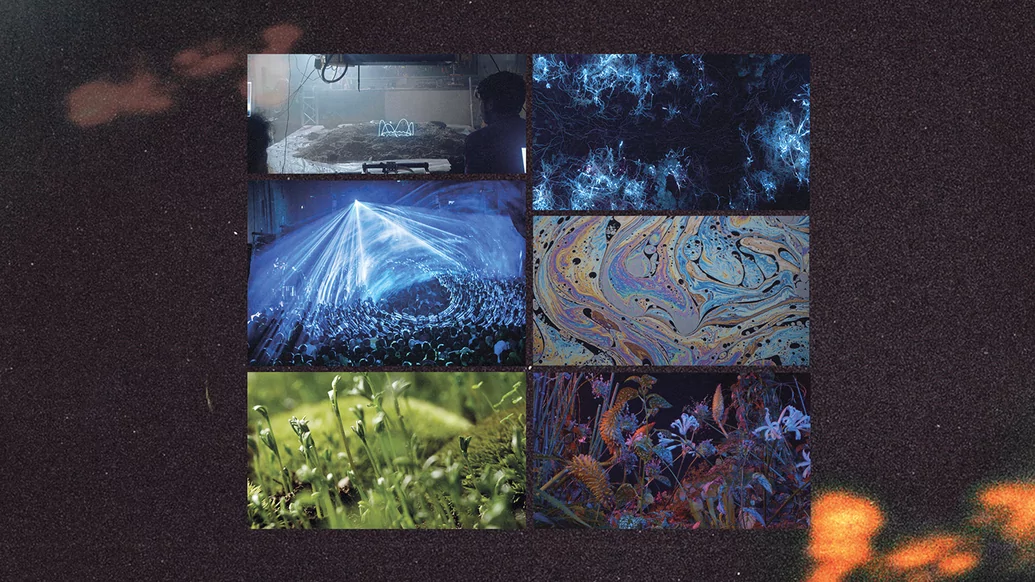

In their use of bubble oscilloscopes and neon vegetation, Anna Diaz and Pablo Barquín are the brains behind the ethereal aesthetics which defined Floating Points’ Crush LP in 2019.

Also known as Hamill Industries, the multi-disciplinary studio partnership is based in Barcelona. They interpret music from an emotional standpoint to envision an end result, experimenting with whatever means necessary to get there. “We’re not married to one type of technology,” said Diaz. “We cross reference different media a lot but are not experts on anything specific. These days, there's a lot of noise around artificial intelligence - which I like, because it makes it more accessible for everyone. I learnt how to code, and it’s liberating.”

Exercising digital techniques to translate the organic world into a visual accompaniment to music, they created the Last Bloom video using stop motion and time lapse methods. “We were interested in how plants interact with other species and how they create networks of communication,” says Diaz. For the Crush live show, they projected a display of real-time bubbles reacting to sound vibrations and musical stimuli. “The idea is that everything is generated live,” says Diaz. “The sound generates visuals, but those visuals react to the sound again. It's a whole circular process.”

AV and creative coding have a huge overlap with the tech sector, often leading to assumed gender roles within the field. “Although there’s been more space made recently, the scene for audio-visual artists is very male dominated,” says Diaz. “People think you are the girlfriend of the musician, or people assume that I’m the manager and Pablo is the creative guy,” says Diaz. “But Hamill is really fifty-fifty, we do everything together. We talk a lot about assumed roles and how we can tackle this in our own practice.”

Kerrie IRL is a multidisciplinary artist from Manchester, combining graphic design, illustration, and moving image. “If I had to describe it aesthetically, I’d go with immersive and textural,” she says. The 23-year-old creative made the CGI cover for Jossy Mitsu’s debut Planet J EP, released on Astral Black later this month. It’s a moody, high-res rendering of London’s skyline, creating a suitable hyper-industrial aesthetic for the bass-heavy production.

“I’m interested in combining newer technologies alongside more physical, off-screen methods of making,” says Kerrie. “I’m a massive nerd for obsolete technology too - the dream would be to raid eBay for super old laptops and PCs, and combine things created on those with stuff made using more cutting-edge software.”

When responding to music, Kerrie repeatedly listens to a track to isolate noises and conceptualise them visually. “Initially I jot down anything a sound reminds me of - a particular texture, material or light,” she says. “From there, I try to link my own experiences with those visual elements.”

As well as creating visuals for Sheffield based club night, Magnetic North, Kerrie has also had her work commissioned for display in Tate Britain - an animated landscape piece exploring the bias of predictive algorithms. “Once everything’s back open, I’m also hoping to put together an AV show with other designers and DJs in Manchester at some point,” she says.

“I’m not a serious kind of guy,” says Weirdcore, the anonymous AV mastermind behind Aphex Twin’s music videos and live shows. “You could probably describe my style as punk and unapologetic... with a bit of tongue and cheek.”

Weirdcore’s visuals are surrealist fantasies, dabbling in British humour and playful real-life references. Be it live projected face-mappings or codified landscapes in the T-69 collapse music video, he skilfully distorts familiar scenes into visions which are infinitely futuristic. “By sharing things that are recognisable, you have more communication with the audience,” he says.

Weirdcore started using Max/MSP as the main software to create his visuals in the early two-thousands. “It’s a bit like a game engine,” he says. “When it’s live, I have loads of local presets and mock modular setups because Aphex never tells us what he’s doing. That's a major difference from any other artists that I've worked with - when you do visuals, you roughly know what they're going to play. But with Richard’s shows, you have to be ready for anything.”

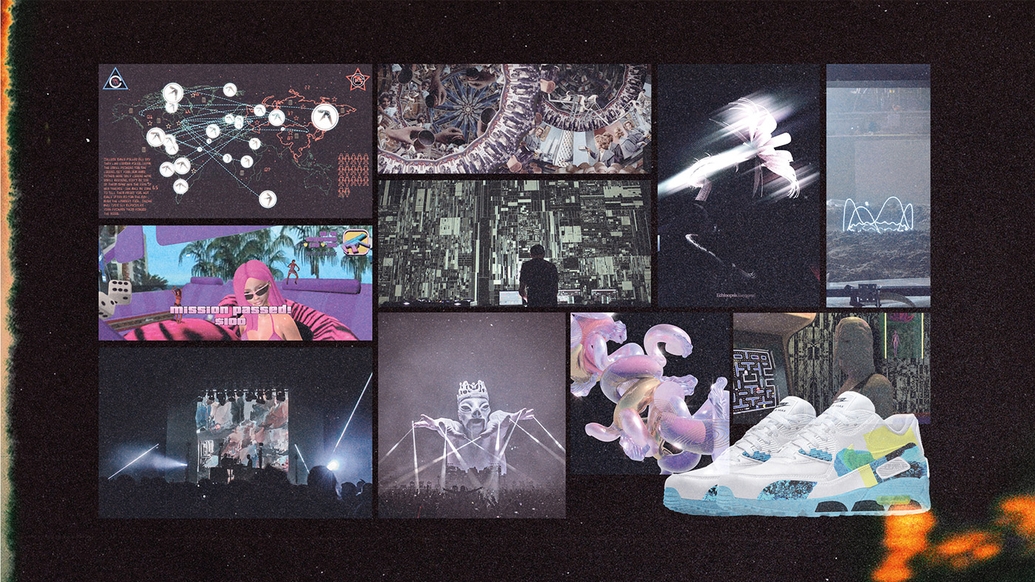

Weirdcore has worked with other major artists including Gwen Stefani and M.I.A, and was involved in the visuals for the 2019 indie rave film, ‘Beats’. “I’m also in the very privileged position to have worked with many of the artists I really admire - like Arca, Slikback, Overmono, and Le Dom,” he says. “At the moment, I’m working on something for Yaeji, commissioned by Bandai Namco who do Pac-Man.”

Weirdcore recently launched his own airport-themed exhibition, Orient Flux, in Beijing’s SKP-S department store: a hyper-futuristic world of interactive installations and multi-sensory artwork. And although it’s still uncertain when live music will return, it hasn’t stopped Weirdcore from generating ideas about how it could. “I recently got a VR headset,” he says. “I think it’s maybe the way forward, if we can't go back into crowds anytime soon. A lot of people are having all kinds of parties on VR - and I’m discussing that idea with certain artists. Definitely on the cards...”

“I’m really drawn to those original grainy flyers from the first illegal raves in the nineties,” says Lawrence Abbott, the London based creative who started out by designing flyers for his brother’s first DJ gigs. “They tend to strike the right balance between ambiguity and promotion.”

Coming from a performance and fine art background, Abbott now works in 3D motion graphics and typography - often animating posters to amplify static designs. “I like to mutate traditional graphics into something more dynamic and bodily,” he says. “Basically, I’m embracing styles from the original acid house era but interpreting them using the technologies of our time.”

As well as collaborating with artists like Kelly Lee Owens and Sherelle, Abbott worked on the creative direction for DJ Bone’s FURTHER event series in Amsterdam before the pandemic. “He gave me a track list of the music he was discussing, and I would re-imagine it digitally,” he says. “I also tried to visually encapsulate some of his experiences from Detroit techno.”

Abbott is looking to revisit some of his previous artistic practice and try out more 3-D modelling. “I do try to harness new technologies as much as possible,” he says. “But the technological period we are in can be overwhelming. I’d like to utilise more performative algorithmic art and poetry, and focus on using accessible technologies but in a different way.”

“I literally just try to make DJs look like the pop-stars they deserve to be,” says Kirsty Sorley, also known as polar fantasy. The London based digital artist taught herself to animate a year ago and has been creating pink fantasylands soundtracked to techno ever since. Using lo-fi graphics and glitchy game footage, Sorley’s main inspiration comes from Y2K-era music videos and early PC virtual chat rooms. “I’m glad all those years as a teenager making avatars on Stardoll, IMVU and Habbo Hotel came into use,” she says.

Although her AV debut was cut short because of the pandemic, Sorley has worked on an animation project for Six Figure Gang’s Yazzus and recently finished the BACK2BACK music video for DJ MELL G and Destroy. Resembling an old school computer game re-imagined in her signature pink pixel aesthetic, Sorley transformed the artists into Tekken avatars for “the ultimate ghettotech dance off.” “Filming a traditional music video doesn’t really match the technology we have at our disposal,” she says. “Music has no boundaries to where it can take you, so why do music videos have to be constrained by the limitations of the physical world?”

The DIGI-GXL online community is playing an essential role in providing a voice for female, trans and non-binary people in the animation scene. “It addresses the issues that have come with software that have been made by men, for men,” says Sorley. “It's no secret that there’s not many girls making videos in dance music - it’s always been a boys club, and it’s only been recently that there’s big and influential DJs who aren’t men. If I hadn’t found the female 3D artists on Instagram that I did, I would have thought I was the only girl animator out there.”

Ezra Miller is a creative coder and generative artist based in Brooklyn. “My interests in art practice and music tastes have always been intertwined,” says Miller. “The main part I find compelling is creating a system which I can control in a very fine-tuned way.”

In 2019, he collaborated with Objekt for his first ever live AV show, pairing glaringly vivid visuals with club-heavy soundscapes. “Visualising the music is actually really difficult,” says Miller. “It’s not an intuitive thing for me. Sometimes it’s just a feeling - you hear something and can see what will compliment that sound straight away. Sometimes it takes a lot of repeated listening sessions while thinking about certain things.”

Although the increased availability of design software has helped to democratise digital art, the implementation of live AV technology in venues still has a lot of catching up to do. “For a lot of venues, it’s expensive and difficult to show visuals in their best form,” says Miller. “But if they are treated with the same kind of technical respect as the sound, it can have a better effect at enhancing the audio.”

Miller created the full album visualiser for DJ Python’s Mas Amable LP and recently shared his own mixes for a FACT magazine residency. At the moment, he’s working on a live streamed AV project to combine both sides of his craft. “I’m personally a huge music fan, and I really want to keep exploring that part of my world,” he says.

“I try to recreate my version of the club atmosphere - be it human or sometimes alien,” says Stacie Ant, the Russian-Canadian artist who builds non-confirming fictional worlds through 3D animation.

“I’m inspired by Berlin’s versatile nightlife,’ she says. “My work is very sex-positive, queer, fetish, and humorous. My inspiration also comes from art-house cinema and alternative fashion, as well as from everyday life - the way I see the world or the way I want to see the world.” In November, DJ Hell revealed Ant’s music video for his Out of Control single: a chromatic fetish fantasy using CGI rendered models of his head.

Ant also made the music video for Tornado Wallace’s Midnight Mania single released on Optimo Music last year: an extremely abstract storyline following distinctive hallucinatory characters. “I want to contribute to shaping the future in some way,” she says, hoping to push her creative practice further by exploring immersive works and public installations.

“There are a lot of visual artists who I admire - but I try to be very careful about what I expose myself to,” says Ant. “It’s important for me not to be too influenced by other 3D artists as I don’t want to subconsciously repeat their ideas or let my style be bent towards what is currently popular or trending.”

Like living organisms morphing into successions of life forms, Max Cooper’s visual narratives follow a beautiful logic: evolving from microscopic structures into sprawling cityscapes and geometric abstractions. Although most widely known for his electronica and techno production, for Cooper, visuals and audio go hand in hand.

“I'm generally always working with visual concepts first, and then making music to fit those,” says Cooper. “The primary focus of my work is creating things which evoke an emotive response.”

Hailing from Belfast, Cooper has a scientific background and holds a Ph.D. in computational biology. “I use a lot of science and philosophy themes in my work, and visualisations of natural systems as my content,” he says. “I need to keep that part of my brain stimulated.”

Cooper collaborates with key visual artists to create pre-rendered stock content which he controls during live performances. Following his major Yearning for the Infinite show at the Barbican in 2019, he took over Belfast’s Carlisle Memorial Church for AVA last November - using the unique interior as a canvas for live AV. “That performance drew on a lot of my content from over the years,” says Cooper. “I focussed on using the structure of the space itself as part of the show.”

Cooper has been working on a new album coming later this year, and also has a couple of machine learning projects in the works. “Machine learning will open up so many doors in terms of composition and sound design,” he says. “The music writing process becomes like interacting with a living thing which has a mind of its own, but is under your control as well.”

Cyriak Harris is something of an animation veteran in the weird and wonderful corners of the blogosphere. Close to amassing 2 million subscribers on YouTube, Cyriak transforms imagery from the banal everyday into complex and bizarre animation overloads. He’s also made the music videos for Bonobo’s Cirrus and Flying Lotus’ Putty Boy Strut, with his most recent project being the video for Sparks’ Existential Threat.

“When it comes to making a music video, the first part of the creative process is to come up with a concept that fits the music,” says Cyriak. “The song acts as a storyboard. Once I have the idea, I start sourcing material to use in the animation, whether its photos or video footage.” He explains that the animation process can be “quite tedious”, with a three or four minute video taking a couple of months or more to produce.

Cyriak also indulges in his own musical production which has become intertwined with his video making: characterised by bouncy, computerised bleeps and dizzy de-tuned melodies. “I started making music as a hobby back in the early 2000s using Fruity Loops, which eventually became FL Studio,” he says.

“The music I make is hard to describe, it's like an electronic LSD fairground nightmare. There was a club night in Brighton called Wrong Music which I used to go to a lot, you can probably imagine the kind of weird stuff they used to play. I guess all that stuff filtered into my own musical creations.”

“I’ve always had an interest in making art that exists in a similar way to music,” says Rachel Noble, a London based virtual artist working in the underground dance music circuit. “More primal, instinctual and intuitive, than conceptual or intellectual.” Noble stopped DJing on NTS to focus on her visual work, creating videos for Australia’s Pitch Music and Arts Festival and collaborating with the likes of Boiler Room and Just Jam.

“I have often used textures from videos or scans of objects and photographs of interesting surfaces into 3D spaces,” she says. Applying collaged visuals to create her animations, Noble’s style is fluid, sparkling with iridescence and cosmic-like plasticity. “My ideas are quite intrinsic - often resulting from emotional reactions to beautiful things I see in the world,” she says. “There is often a theme of anti-gravity and weightlessness - I like to bring that ecstatic feeling to the forefront when it comes to club visuals.”

Noble turned to music in an attempt to bring a sense of freedom back to her work after art college. “The creative industries are undervalued by society in general - so I think that really causes problems for those who may be from a less privileged background to take the risk to follow a creative career,” says Noble. “I really feel that changing the way that society values art and music will enable a more diverse group of people to follow a creative path, whether that be in visual art or music and club culture.”