Motor Bass: how car culture influences electronic music

Cars and music have worked in tandem for a long time. With genres such as Miami bass and trap, cars have inspired the growth of scenes, while in hip-hop, gqom and synthwave, the connection is more nuanced. Ben Murphy explores the connections between car culture and music production

"Being in South Florida where the weather’s warm and the public transportation is not reliable, you had to have a car to get around,” author Dave Tompkins told WLRN Public Radio in 2016 — explaining the connection between Miami’s love of automobiles and its attendant music scene. “What better way to show off your car or your system than to have these booming sounds?”

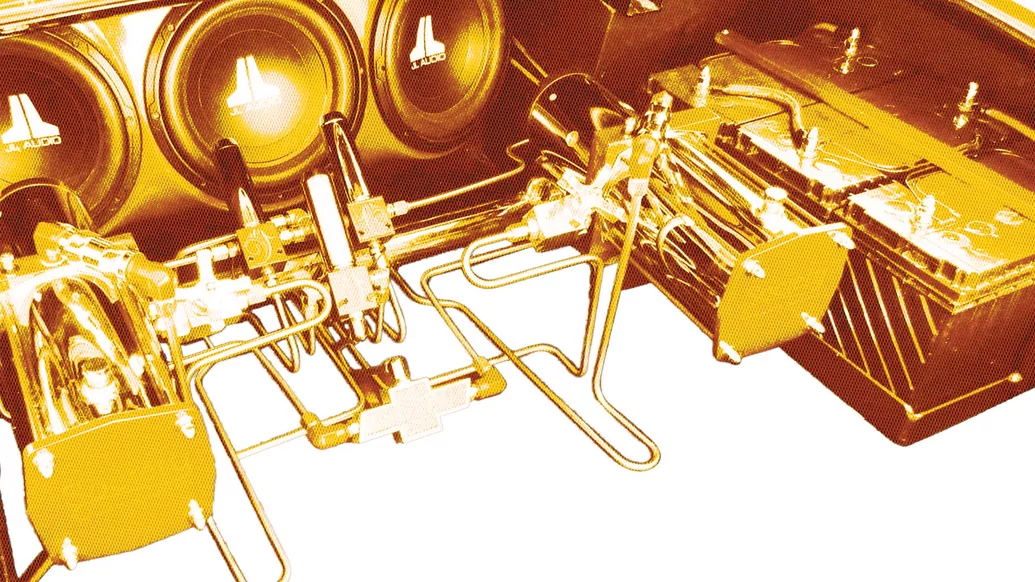

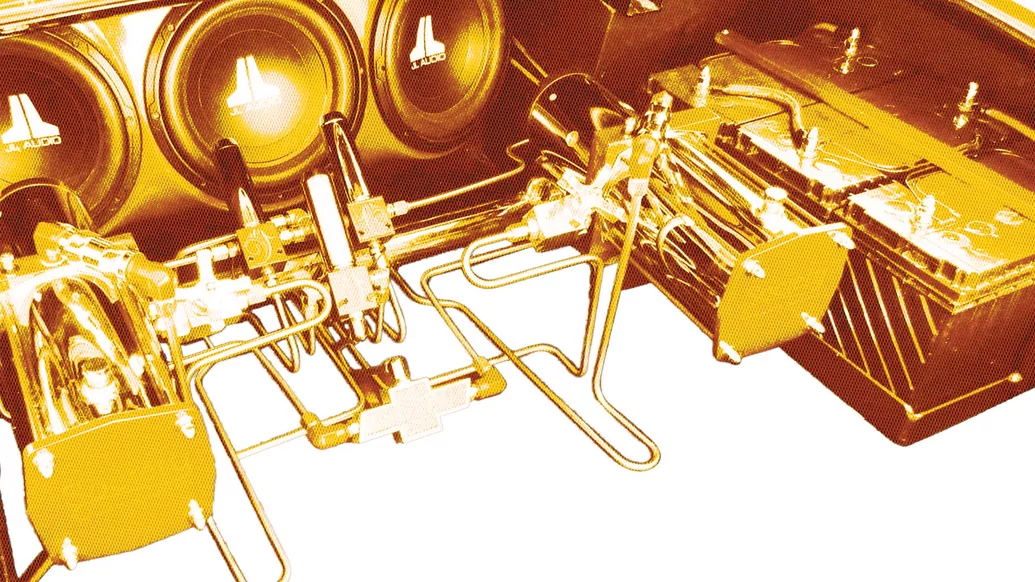

From Florida’s state capital in the 1980s, through to ’90s Los Angeles, Newark in the 2000s, and Durban, South Africa in the 2010s, cars have driven the development of many genres of dance music and styles of hip-hop. Think of the rippling sub waves of Miami bass, or the distended 808 kick-drum hits of trap; the thudding breakbeat rhythms of Baltimore club, the ‘Ridin’ Dirty’ rap of Houston’s UGK, or DJ Screw’s chopped and screwed, slow-as-molasses grooves. All these forms are designed for play on souped-up car soundsystems, with bass at the forefront to put automotive sub-woofers through their paces.

In an extension of the custom car culture that has owners personalising grilles, spoilers and tyre rims, investing in candy-hued paintwork, or adding hydraulic ‘low rider' systems to their rides, music has influenced how drivers modify their vehicles. In turn, how cars are used — not just for transportation, but for recreation also — has inspired the birth of whole music scenes.

This symbiosis between car culture and music production is represented most in the USA, where the vast distances make having a car practically essential. “Cars have always been a huge part of American culture,” says Jersey club pioneer and hip-hop/B-More producer DJ Tameil. “From as far back as I can remember, through the ’80s up to now, loud soundsystems with a lot of bass have been a must for many in their vehicles.”

The USA has a famous automotive industry (Ford, Chevrolet or Tesla just for starters), and cars have long been part of American popular culture, dating back to the 1950s iconography of drive-in movies or late-night diners. Car modification that changed the suspension of vehicles, allowing them to be raised or lowered hydraulically, and thus become ‘low riders’, started in LA’s Latino communities in the ’40s and ’50s, and subsequently became popular in African-American culture too. This customisation was celebrated in funk band War’s 1975 hit single ‘Low Rider’, and ever since, music has had an intrinsic bond to cars in Los Angeles.

Hip-hop especially made the link explicit in the city. Egyptian Lover’s 1984 electro rap cut ‘Egypt, Egypt’ had booming Roland TR-808 bass designed to test car woofers to their limits, while in the ’90s, tunes like Dr Dre’s ‘Let Me Ride’ boasted of having “16 switches” for operating a low rider, and a music video where the vehicles took centre stage. References to Chevrolet Impalas or Dayton wire tyre rims peppered the lyrics of Cali MCs, and the sound of West Coast gangsta rap had a slower, sunnier aspect than its gritty New York progenitor. This LA variant was propelled by wiggly keyboard lines, a laconic pace, and synth bass designed for playing at high volume in slow-moving vehicles.

"NY rapper Masta Ace, influenced by this car-connected sound, had hits with ‘Sittin’ On Chrome’ and electro synth-bass track ‘Born To Roll’, with its “I got the woofers in my jeep” lines and auto show music video. New York City, not to be outdone by its Californian rival, would popularise the idea of “jeep beats”, meaning rugged hip-hop tracks for bumping in your car while patrolling the streets.

Miami, though, is the city where cars have become most interwoven with music culture. The Florida metropolis gave birth to Miami bass in the mid ’80s — a genre initially conceived as a response to the electro/hip-hop scenes in NYC and LA. Quickly, Miami bass took on its own distinctive characteristics. Artists like 2 Live Crew (and their producer, Dr ‘Mister Mix’ Hobbs), Maggotron. Dynamix II and MC ADE focused on a speedy, minimalist form of electronic dance music, with sexually suggestive lyrics, a plethora of familiar micro samples, and most of all, heavy drum machine beats. Most prominent was the bass component: the Roland TR-808’s unmistakable kick-drum boom was prized above all. In the simmering tropical climate, Miami bass could be heard pumping from automobiles around the city, as car owners competed for soundsystem supremacy. “When Miami bass appeared in the early ’80s,” local producer Bass Mekanik told Electronic Beats, “the whole bass experience was intensified by the faster, dance-oriented tempos. Immediately you had a party on wheels.”

Mixpak crew-member and New York resident Jubilee grew up in Miami, and vividly remembers the connection between music and cars there. “I knew more about speakers than the average 10-year-old thanks to song lyrics, and kids in my class being really into car magazines and having older brothers and sisters,” she says. “There were definitely a lot of next-level car set-ups and shows, but I personally think it was more important that there were a ton of regular Civics, Eclipses and Accords with systems in them, and a cool spoiler or rims. It was a total thing. I remember my boyfriend from middle school had an older brother, Rob Booke, that always used to pick him up from my house, and you could hear his car from a mile away. It was lowered and had neon on the bottom of it. I also think he introduced me to a lot of music and knowledge of bass, just from literally sitting on the phone with them all night because it was the ’90s. They used to play bass tapes with no lyrics that were specifically for his car. “When I turned 18, I bought myself my own little system for my tiny two-door Toyota Paseo. It was an amp and two Rockford 10-inch speakers. I have certain relationships with certain songs because of the way they sounded in my car.”

Soundclashes

The scene’s connection to vehicles was immortalised by rap duo L’Trimm’s hit record ‘Cars With The Boom’ in 1988, a tune that celebrated the 808 thump that reverberated around town. As some car owners began to outfit their entire trunks with elaborate sub woofer systems, a culture arose of soundclashes between cars in parking lots, with only the most enormous bass responses passing muster. From this, a more niche variant of Miami bass arose: car audio bass. Producers such as Jamaica-raised Bass Mekanik (Neil Case) and DJ Magic Mike made their tunes specifically with the car audio enthusiast in mind, with low-end so thick it could bust inferior speakers.

“All the stores that specialised in car stereos were selling and using my stuff in their installations,” Bass Mekanik told Electronic Beats. From the unofficial soundclashes evolved competitions organised by the International Auto Sound Challenge Association, and these skirmishes soon became a spectator sport in the city. “Contemporary hip-hop is now all about the bass, and even other genres like rock, country and R&B have far more low-end than they did 20 years ago,” Bass Mekanik said to Red Bull Music Academy. “This lust for bass comes first from car audio.”

Miami’s proximity to the Caribbean and history of immigration from the islands — especially Jamaica, with its plethora of bass-driven styles of music — may be one reason why such a strong bass culture has taken root there. Before moving to Miami, Bass Mekanik had his own reggae soundsystem, and still makes reggae stuff as well as car audio bass. The experience of growing up around the car culture in Miami still influences Jubilee’s approach to music. She needs to hear how her productions sound in the car before she’ll release them.

“Moving to NYC and not having a car completely changed the way I listen to music,” she says. “I can't listen to music the way I used to on the subway with headphones on. Every single thing I produce gets ‘the car test’ before it’s finished. I have rented so many cars in the past to listen to my own productions in over and over and over again while I drive around with the windows open.”

Slow, Loud & Banging

Around the rest of the US, the car culture helped galvanise local hip-hop scenes. In Houston, the ‘slab’ car phenomenon grew in tandem with the rap movement in the city. Slab, an acronym for ‘slow, loud and banging’, denoted both the style of beats played in the rides, and the slab car’s elaborate style. Custom-built from a variety of American luxury vehicles, with a low suspension, usually with rims that protruded from the tyres (known as ‘swangas’) and candy paint, slab cars were essential for bumping out the local variant of hip-hop. Made from leisurely beats and bass that marinated in the heat haze of the American South, tunes by gangsta rappers Geto Boys set the groundwork, while UGK — another popular Texan group — had a big hit with ‘Ridin’ Dirty’, their ode to avoiding overzealous cops while driving with contraband in the ride.

But it was the production of the late DJ Screw that really changed this iteration of the Southern sound. Slowing the beats and raps of popular hip-hop songs down to a languorous crawl, his “chopped and screwed” mixtapes, which began to gain traction around 1995, sounded like wading through a sea of treacle, and instantly became the soundtrack for car owners to roll slowly to in their slabs — sometimes intoxicated by the potent codeine syrup, aka ‘purple drank’, also associated with the scene. Hit tunes influenced by this sluggish groove emerged, taking it into the mainstream, such as Mike Jones’ ‘Still Tippin’’: another ode to cruising in cars around Houston.

A variety of other mutations (or evolutions) of hip-hop occurred around the US as these Houston forms sprang up, always assisted by the prevalent car culture. In Memphis, the crunk style of Three Six Mafia, driven by gaudy keyboard riffs and 808 drums, got popular in strip clubs but soon was heard emanating from cars across the US. New Orleans bounce artists like the late Magnolia Shorty and Big Freedia mixed upbeat electronic rhythms with call and response shouts and raps, with one of the biggest ever nationwide hits in the genre, Choppa’s ‘Choppa Style’, featuring the MC driving around and performing in front of candy-painted trucks.

Arguably the most car-friendly form of hip-hop to arise in recent years, though, is trap. Born in Atlanta and quickly adopted around the South, this form of rap slowed down the drums to 70bpm, with hi-hats double the speed; a sheen of synths, raps doused in AutoTune FX and, most importantly of all, 808 kick drums with slow decay, creating a super bass-heavy style of music where rhyme style prowess was less important than sub-wave pressure.

Now the dominant form of hip-hop production across the US (and the rest of the world), trap beats are calibrated to make whole cars — and streets — vibrate. Trap is part of the lineage of programmed beats that sound so good in a car, but which are miles away from the original New York hip-hop sound. As Simon Reynolds points out in his trap feature for The Face: “When the party-oriented, shake-that-ass sounds of Miami bass and New Orleans bounce fused with gangsta rap lyrics, trap was born”.

Trap producers, such as new breed hotshots WondaGurl, JetsonMade and Kenny Beats, have fine-tuned the art of bass production, while the videos of trap artists frequently feature futuristic rides — Migos’ 2017 hit ‘MotorSport’ featured not only ridiculously expensive autos like the Ferrari Testarossa and several types of Lamborghini, but a prototype Lyft flying car.

“When I produce tracks, not only do I EQ and master the bass just right for my monitors, but I take it out to test it in my truck and then also on my own soundsystem or at a club when I DJ before releasing it” — DJ Tameil

Whereas hip-hop has slowed down its tempo considerably in the last 20 years, other local, bass-heavy dance music forms in the US have maintained more frenetic pace. Baltimore club and its musical cousin, Jersey club, are styles that sprang from the dancefloors of Maryland and New Jersey, mixing chopped-up breakbeats, samples from rave, house and rap, and again a thumping bass drum that works equally effectively on dancefloors and in a set of wheels. Illustrating the connection between cars and Jersey club was UNIIQU3’s music video for the track ‘Trunk’: filmed in an auto shop surrounded by car rims, the track featured a distended b-line and a lyric extolling the virtues of a “Badonkadonk / Bangin’ like some bass in a trunk”.

One of the pioneers of Jersey club, DJ Tameil, part of the Brick Bandits crew in Newark, has also made Baltimore club tracks, and has been an active DJ and producer on the scene for many years. In the city, he says, Jersey club will frequently be heard thumping from passing trucks.

“I’m currently waiting for things to get a bit calmer with the pandemic so I can shop for a new system to put in my 2019 Nissan Pathfinder to shake the block!” he says. “Loud, rumbling systems are still a thing here, and daily you can still catch people riding around with souped-up soundsystems, blasting Jersey club and more. Cars with loud systems are here to stay.”

Like Jubilee, Tameil needs to test-drive his tunes before he releases them. If they don’t sound good in the car, it’s back to the drawing board. “When I produce tracks, not only do I EQ and master the bass just right for my monitors, but I take it out to test it in my truck and then also on my own soundsystem or at a club when I DJ before releasing it,” Tameil says. “Everything has to hit just right, otherwise it doesn't sit well with me. I can say that, for many producers in the Jersey and Baltimore club genres, the kicks, basslines and all have to hit heavy.”

Both B-More and Jersey club have spawned local dance crazes, and the moves in Newark in particular serve to show how much the culture is influenced by automobiles. “The dances are one thing in Jersey that spread back much further before even establishing this particular style of club music and branding it ‘Jersey club music’,” says Tameil. “Back in the ’90s, we had popular dance moves like ‘The Stolen Car Dance’ or — as we called it in the Brickz (Newark) — ‘The Lock It Up’. That term came from locking the brakes on a stolen car to do donuts, which, not proudly, was a huge thing. We were labelled ‘The Stolen Car Capital of The World’ back then, because either your car may be stolen or you might be carjacked.”

Taxis

In other parts of the world, car culture meets music in more unexpected ways. In South Africa, where house and a regional variant, kwaito, have long been popular genres, tunes are often popularised by local taxi services. In Johannesburg, kwaito became big after getting played by cab drivers. Spurned by the radio stations, kwaito producers turned to the taxis to get exposure for their tracks. With cabs a primary source of transport for many of the population who didn’t own a car, passengers were exposed to four-four rhythms. House eventually became the dominant style of music in South Africa, with taxis playing an important part in its rise.

In Durban, the taxi phenomenon has helped to raise the profile of another newer SA electronic genre: gqom. Characterised by its broken beat rhythm, kick-drum thump and swelling, sinister synth strings, gqom is a more minimalist and mechanistic form that has accumulated a big following in South Africa and in clubs around the world since it started to emerge around 2012. As in Johannesburg, producers from the Durban townships — such as Citizen Boy, DJ Lag and DJ Mabheko — couldn’t get their sound played in clubs, so asked local taxi drivers to play their tunes. Soon, a rivalry came into play as the taxis realised they could capitalise on having the hottest gqom tunes.

“The taxis used to have these big subs,” says gqom pioneer and producer Menzi. “They all wanted to show off that my car is louder than yours. They wanted to compete with each other, but they didn’t have the right sound — music that’s gonna pump, that’s gonna have minimal sounds, that is gonna be loud enough, ’cause house is sort of soft music. We started sending the music to taxis and they started playing gqom. Taxis started asking us for songs, and it was a platform for us. People from other cities would know about you, that there’s a guy who is doing this music in Durban.” The only other place gqom could be heard in public in Durban was at house parties, so the local taxis used the hottest tracks to drum up business, pumping the tunes loud from their souped-up soundsystems, creating another notable symbiosis between cars and music.

“If you’re playing the most popular sound, people will want to ride in your taxi,” Menzi says. They are attracting people by playing gqom music.” Still, he points out that taxi drivers can be fickle when it comes to genre, and another style of South African deep house, amapiano, is becoming the new taxi sound in Johannesburg and Pretoria. “Some genres are moving in. Now there’s a genre called amapiano, so they’re saying gqom is dead. We want to have a sound that can beat amapiano, and bring back gqom.”

Drive

While these different styles of dance music and hip-hop have a physical, real world bond to automobiles, there’s another genre that celebrates them in a more abstract way. Synthwave — a type of melodic electropop rooted in 1980s culture that references everything from the soundtracks of John Carpenter and Goblin to 8-bit video games, bands like The Human League and Visage, andsci-fi and horror films — also fetishizes certain cars and driving as a whole. Netflix programme Stranger Things and its score by S U R V I V E helped bring synthwave into the spotlight, but synthwave’s first moment in the mainstream came with Nicolas Winding Refn’s film Drive.

Focusing on the heroic redemption of a criminal gang’s getaway driver, the assortment of glossy, hip synthpop songs on its soundtrack made plain the link between slick wheels and sounds. Since, the iconography of upscale vehicles can be seen in the videos of many synthwave bands and artists dabbling with the genre, like pop megastar The Weeknd, whose ‘Blinding Lights’ song taps into the sound and has the singer burning around in a slick Mercedes AMG GT in the visual.

Welsh group Taurus 1984 feature a DeLorean in the video for their song ‘Dream Warriors’, the futuristic car made famous for travelling through time in the Back To The Future fi lms. For Alastair Jenkins from the band, vintage cars tap into the same sense of nostalgia that synthwave itself hints at: that idea of an unattainable past that maybe never really existed in the fi rst place. “I think the two elements of synthwave and retro cars are a perfect match together,” he says. “Aesthetically they both play off each other. I feel it really taps into the idea of a form of retro fetishism or the persuasion of a golden-age thinker: a feeling that another time was more pleasing visually or audibly certainly comes into it. Vehicles from that period of time were really pushing boundaries with their appearances, and were so heavily influenced by futurism. It plays into the whole ‘fantasy’ aspect of the genre of creating this other world, something more futuristic, yet simplistic and aesthetically pleasing. Neon, arpeggiated basses and beautiful cars. Say no more.”

Jenkins reckons that fi lm and TV, and the way they used popular music during the ’80s, has resulted in synthwave’s inevitable marriage of retro imagery and sound. “Drive did huge things for the genre and really exploded it into mainstream consciousness. It was really my (and no doubt a lot of other producers’) first experience of that sound. Some of those scenes are so iconic now. It really helped solidify the marriage of the two elements; modern synth music and the car aesthetic together as one package. Films such as Risky Business, which features a wonderful score by Tangerine Dream, also play a big part of this relationship of synth and gorgeous cars (that Porsche 928). Miami Vice (the scene featuring ‘In The Air Tonight’ by Phil Collins could be the first true example of the meeting of synths and cool cars) can certainly be cited as another factor in the development of the appreciation too.

“If you watch a lot of films or TV shows from the 1980s, you’ll notice that cars play large roles in many classics from the era, almost as much as some of the main characters do,” he continues. “Look at examples such as Back To The Future, Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, Christine, The Wraith and Knight Rider to name just a few. There would be great driving shots in these movies accompanied by cool synth-led music to create this incredible and enticing atmosphere, that I suppose many of us are trying to reference and elaborate on.”

A less glamorous but nonetheless notable iteration of the connection between cars and tunes is in how rave tape-packs were voraciously consumed by young drivers in the UK in the early ’90s. Bumping a Helter Skelter or Dreamscape mixtape or a ‘Bonkers’ compilation in your own car was a seductive prospect for many prospective motorists, giving an added edge of prestige for those getting behind the wheel for the first time. A fair proportion of drum & bass and UK garage producers would also test out their new tunes in their motors, too. Ultimately, the reason cars and music go together so well is the sense of freedom each impart: a sense of motion and escapism are present in driving or dancing, or even just listening to music. With COVID-19 showing no signs of going away, mooted drive-in gigs or dance events point to yet another new way that cars and tunes go together — and may even help the music survive despite the current crisis.

“Right now no one can go anywhere because of the pandemic,” says Jubilee. “But if you fi nd the right little pocket in NYC on the weekends, you will witness the most wild car sound-offs. Cars with speakers on top blasting reggaeton, and hookahs everywhere, just somewhere under a random bridge. It’s still bringing everyone together over music right now.”