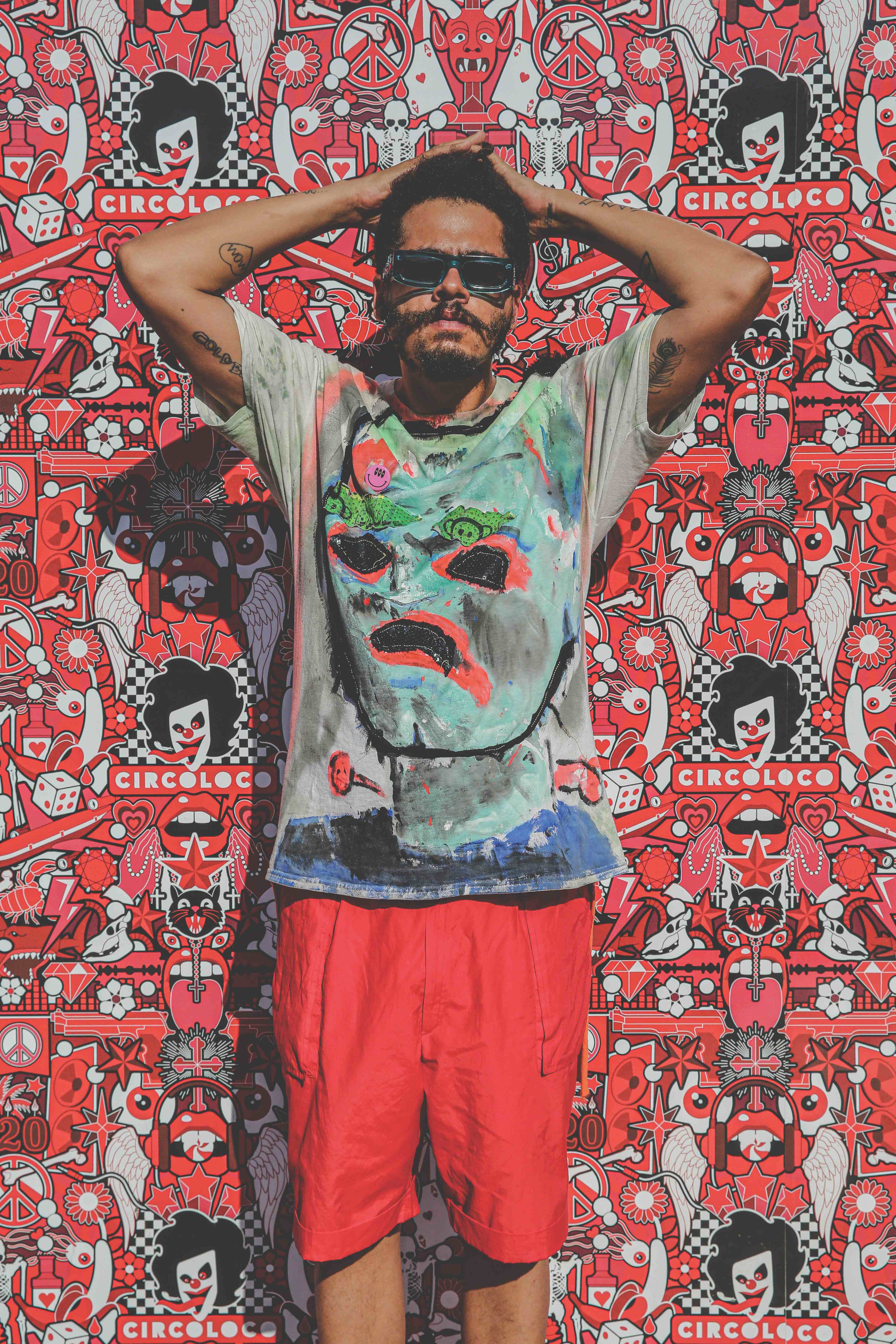

The many faces of Seth Troxler

One of dance music’s most recognisable characters is growing up. We talk to Seth about the repetitive party lifestyle, being a catalyst for change, and why electronic music culture means everything to him

Seth Troxler’s reputation is such that he’s on first-name basis with the whole of electronic music. He’s put himself out there — often literally — to the point that he feels like a cheeky pal, a symbol of the sesh, a rep of the party. We all know a ‘Seth’: the lovable rogue who’s the last to go to bed, the devil on our shoulder; the one who’s dragging out the afters, when there’s nothing in the tank.

In 2019, it’s a reputation he’s keen to leave behind. Nine years on from topping the Resident Advisor DJ poll, he’s found himself living in Ibiza all year round. He’s a resident at one of the world’s most respected club-nights, DC-10, recently featured at the Saatchi Gallery’s Sweet Harmony exhibition, and is about to host a free party at DC-10 with legend Tony Humphries on September 24th — all while relentlessly and articulately contemplating electronic music’s trajectory, and his role within it. When Seth talks, he means what he says, often tripping over himself with passion, his mouth unable to keep up with his darting thought process. But he rarely stumbles, somehow finding a way to deliver a succinct soundbite on almost any topic.

Time has also brought with it a less dismissive, more considered Seth. He’s slower to judge or name-and-shame, two things he admits he’s been guilty of in the past. Maybe it’s the siestas, or the Ibizan way of life — maybe it’s the natural curve of time — but Troxler has calmed, and with it, a sense of pensive purpose has emerged. As we sit down to lunch — the ceviche was excellent — we start by addressing the reputation he now feels he’s surpassed.

Does it bother you when people just think of you as ‘Seth the Brand’, or have expectations of you when they meet you?

“It’s slightly annoying when I’m doing other things like the Saatchi Gallery exhibition, or the Lost Souls Of Saturn project. A lot of the things people know me for I was doing when I was much younger, like anyone who’s 25, except mine were documented. There was a time when my personality overplayed the music — even though the music was really good, people always remembered me more for the personality. Now I want my lasting memory to be about the music, or things that I contributed, that really changed things.

“As a whole, those hedonistic days have changed, and a lot of the scene is a lot more cautious and healthy. A lot of that behaviour isn’t acceptable anymore, and that’s cool. I’m happy I aged with it in the right way and changed kinda naturally.

“I think I’ve expanded my mind to the point now where it’s time to use it. I think some pretty far out things, so let’s create them! At the Saatchi Gallery I was talking to some people, and so many of them are the biggest people in the creative industry in the world — huge art directors, musical directors — and all these people used to just be rave cases. Electronic music is such a great petri-dish for arts and culture. The people who come up with all the ideas of tomorrow. I and many of my friends are all part of that petri-dish. Now it’s come to the point where it’s our time to create the ideas we’ve had from that brave playbook.

“I’m in my mature years of DJing where it’s more like a seasoned pro, rather than a fresh new kid. I’m older and it’s a different thing I want out of electronic music, and it’s a different thing I’m contributing to electronic music.”

Was there one moment that triggered that change?

“Well, the famous DJ Mag interview [“Bats!”] in Miami to now — I’m still the same person, and musically, more than ever, I’ve zeroed in on what I’m trying to do and say. At that time I was 25 — y’know? — a young kid. The year before, I got the Resident Advisor number one, and it was really the start of my career. That interview took me to the next stratosphere. Now, a lot of artists are part of the internet age, but I was one of the first sensations, off the back of Resident Advisor and all these things. Now I’ve got to a more mature point in my career. My demographic’s changed, my focus has changed, creating more culturally important parties. It’s cool to feel revitalised.”

Was it boring you?

“Yeah, in my ways — and I hate to say this — that repetition of party culture did get a little boring. I love electronic music and the culture around it. That’s what excites me. I love the hedonism of electronic music, but at some point the hedonism became decadence, and that’s when I stepped out. I like hanging out with people who are partying and being mad-with-it based on their expression of freedom, but I don’t like being around a bunch of rich people who just wanna party and get on it. That’s not really my scene. So I’ve taken a step out of the party culture to an extent.

“Even the party culture here in Ibiza [has gone in that direction]. It turned from being a culture of the people, where everyone’s excited, to something more gregarious and something for the rich. And often, rich people aren’t really cool, y’know? They haven’t got good chat. They got a lot of money but they don’t got a lot of chat. It’s the same with beauty. You have to be geeky and ugly at some point in life just to be ridiculed — braces in school, move from a different place. Tragedy has to happen to you in your younger years to be cool later. Ibiza was like a home for all those people, we made a family for the black sheep.

“But now electronic music has become middle-class or upper-middle-class, it doesn’t have that edge anymore. Often, I get ridiculed on the internet for trying to be too political — people are like, ‘Leave the music to the music’, and they don’t wanna be challenged. That’s a very middle-class response, rather than something based on people who like being challenged. I got into electronic music because I wanted to be ‘other’ — it challenged me and it challenged the people around me, it shaped me into the person I’ve become today. Now, I want to create ideas for people to have those same situations, for people to have those same challenges that I had.

“Ibiza wasn’t just about the outsiders; it was just for people who had an open mind. It was cool because the rich, the poor, everyone met on the same dancefloor. Over the past few years the island has admittedly taken towards catering to the bottle-service crowd. That’s happening globally; they go to Mykonos, they wanna show off. That’s not really culturally what we’re about.”

How did you end up making your way to Ibiza in the first place?

“I first came here to start my residency at DC-10. I’d never come before that. During the time the club was shut down, they were looking for some new residents. I had met Antonio [Carbonaro, DC-10 and Circoloco co-founder] in Salerno [Italy], where he’s from, and they asked me to join them. The two new people they asked to be residents were Jamie [Jones] and I. The rest is kind of history. I was just starting up then, and I came here and met lots of cool people, young people who just wanted to have fun and make parties from all different parts of the world, but our cultural ideals were the same. Everyone was up for it. I think now, what the island is missing and why certain things have gone towards the rich is that those certain young people couldn’t afford it today. The people who create the after-parties, who create the general buzz, who wanna go out and make things happen. It’s not people in their 40s. You need that buzz of youth to create that real underground, fun, dance-forever culture.”

Tell us more about the party with Tony Humphries. Why did you decide to make it free?

“I was in Chicago with Michael Serafini at Gramaphone Records, and he was telling me that there was a Tony Humphries record collection up for sale. I was like, ‘Fuck! I really want to purchase these records’. By the time I got a contact the collection was gone — later, I found out it had gone to Gerd Janson, so at least somebody good got it. Through that I met Tony’s manager, and she told me he was coming to Europe this summer and asked if we wanted to do some dates. It turned out he was on the island a few weeks in September, so I went to Antonio and said, ‘I really wanna do a free party at the club, a day party like the old times’, and they agreed. With the surging prices in Ibiza, it’s nice to build something that hopefully lasts and that the whole community can enjoy together, and where there are no differences between people — it’s a cool thing to do. I had the most fun in the daytime here, so I wanna bring back that idea. If I want kids to keep coming back — to have the experiences that changed my life and gave me so many great friendships — I wanna give them those same opportunities to make those connections, friends, and incredible memories. That was the idea behind it. You don’t have to wait till five-o-clock to do something, come down early! I’ll be playing from the beginning, the music will be great, there’s nothing else to do — stop getting high in your house and at least take a pill in a garden.”

You should put that on the poster...

[Laughs] “Yeah, that’s a good slogan for the island: ‘Ibiza: Get High, Outside’.”

But your party is the exception, right? Everywhere is expensive to get in, DC-10 is expensive to get in, and once you’re inside, it’s still expensive. I guess the question is, if the kids stop coming now, what happens when the current party-goers have grown out of it?

“Exactly. It’s not self-sustaining. I wanna be the catalyst for change. Let’s say it goes really well, and loads of people turn up, then maybe it’s showing these other people or other clubs that opening in the daytime brings back that fun party vibe, and for free. You make a killing on the drinks anyway, and free parties are cool.”

Whose responsibility is it to ‘save’ Ibiza, if it indeed needs saving? Is it the DJs? The promoters? The clubs? The visitors?

“It’s a mix of everyone. It’s down to the DJs, promoters and the clubs to leave people with experiences they remember forever. Those were the experiences that brought us back, the great friendships we made, that’s our responsibility. If clubbers are choosing to come here and experience this, and we’re ambassadors — me especially as a resident at DC-10 — of this island. Creating experiences for people is really everything. I live here all year round. I love it. My friends live here — this is my community. When I was throwing parties in Detroit as a kid until now, I’ve always wanted fun things for me to do around me, and now I feel there’s less and less nights that I personally would like to go to. There’s real culture happening in electronic music that’s so rich, and there’s no excuse for one of the homes of electronic music, and one of the inspirations for it, to not be at the forefront of that culture.”

Does Ibiza still have a role in the global scene? Are DJs and records still broken here?

“I think it does, yes. There’s a lot of representation here, because you’re able to reach just a vast crowd of electronic music fans. It’s not totally over here yet, but it’s up to us to keep it relevant. If you have the star power here, you need to do things revolving around the culture and bring back the influence of Ibiza.

“Right now we’re in a transition phase. Every 10 years it goes through this gentrifying period, and then the underground comes back. Kind of like fascism. The Tories come back to the island, everything goes to shit, eventually they leave and go to Mykonos — or hell — and then you’re left with people trying to take back the island and return it to what they originally had that was really cool.”

In a recent panel during IMS Ibiza, you asked a question and said that when you started getting big money for bigger gigs, the crowd became a lot worse and you ended up taking less money so that you could play better parties again. Do DJs have a responsibility to promoters and to the scene generally to reject the higher fees to sustain underground clubbing culture?

“It just makes you feel like shit! I’m from the Midwest. We pride ourselves on our morals and beliefs and if you can’t stick to what you believe in because you’re getting paid a bit more money, it’s pretty bad.”

It’s not that simple though, is it? There’s agents, managers, who all profit from your fees increasing and it might be more subtle than how you describe it...

“I can’t be all high and mighty. I put a price on my morals to play in Dubai and when someone met that price, I went. I like Dubai now! But I thought, ‘If I’m gonna morally take a step back, it’s gonna cost you’.”

You’ve said the word ‘culture’ about 100 times since we met this morning. I don’t think that’s a coincidence. What is it that makes you feel so strongly about the cultural aspects of electronic music?

“It’s not a coincidence. I was very fortunate when I was growing up. My mom invested a lot of time making sure I went to cultural experiences, taking me to museums, taking me to a Degas show when I was five, enrolling me in art classes. It gave me a real globalised view of what the arts, music and culture was — the whole Detroit electronic music scene was always about concepts. Over the years, all the curation of all the labels I’ve done, it’s always been about creating some kind of idea and being immersed in culture.

“Now that I’ve gotten a bit older, and maybe have a bit more money, I’ve gotten more into the arts, because I can afford to be. It’s quite a middle-class hobby to collect art or to go to museums, but at some point through the years I just got to a point, especially with electronic music, where I thought, ‘I’ve accomplished so much, so what else is there for me to do except play raves?’ I feel great playing underground clubs and raves every weekend, but when I look at what else is out there culturally, where we’re pushing the limits of electronic music, I felt there’s space to grow.There’s space for us all to push more. There’s also a whole set of ideas from the arts world that a lot of people in electronic music, especially younger people, would find to be really interesting. And I started looking at all the clubs, places like Trouw where I was a resident, or PIP in Holland; they’re all based on these high-end art backgrounds. Holland and Germany have looked at club culture as high art for a long time, the same way you’d look at dance or contemporary art.

“If we want to expand the culture of dance music, we need to look at who we really are. It’s not about ‘branding’ or ‘me, me, me’. I think I’m at the point in my career where that stuff doesn’t matter to me anymore. It’s not about looking like a star, it’s about ‘After I’m done, what will people look back and think?. What did I actually add to the overall, long arch of electronic music culture? What can I say to myself? Was it worth it? I spent my whole life doing this — what did I give to people?’ I made a lot of sacrifices, too, but at the end of sacrifice you wanna see the worth of it.

“Yeah, I took some jets, I had fun with my friends but I wanna see what’s different. Electronic music’s also at a place of legitimacy, or taking the next step in legitimacy and the Saatchi show is a great example of that [Saatchi Gallery, London is running an exhibition on the history of rave culture called Sweet Harmony]. Rave culture is the last great pure human movement. We’re too connected now to have anything like that ever happen again. Dance music is the final human musical movement to be created organically, in terms of a mass movement of people. I like talking about these cultural things because I think electronic music could take a step into the academic world, and stop being so superficial. Be more legitimate with its reviews, be more legitimate with its critiques of itself. That’s important to me.”

You bought Dave Haslam’s record collection, right?

“Yeah, it’s about half my collection. I have about 9,000 of his.”

Do you ever feel overwhelmed by choice when DJing, and just find yourself reaching for the same records ‘cause you know they work or go together?

“Not at all. Stagnancy is my greatest fear. To do the same thing too many times, if I had to do something like that, there’s a high probability of suicide. I’m crazy like that, it sucks the soul out of me so much.”

You can see how it happens, though — you know tracks that are in the same key, it worked last night, you’re on tour, crowd goes crazy...

“I don’t even make playlists. Half the time I don’t even know what I’m doing up there. That’s why it sounds kind of surprising, because it’s surprising to me. There’s a lot of people in our scene who do become complacent, and I know some of my peers who’ll be like, ‘I’m just gonna play the same set as last night’ and I’m thinking, ‘I can’t even play the same music two nights in a row’. But that’s the changing tide. I can’t think there’s something wrong with the new generation thinking like that, coming from an entertainment background. But coming back to the word culture, I want to express things with a different cultural sphere and I want to preserve that idea.”