Joaquin “Joe” Claussell's spiritual vision

For New York DJ, artist and label boss Joaquin “Joe” Claussell, music is about spirituality and togetherness. With a new album, ‘Raw Tones’, released this month on Rekids, reflecting a new side of his production, DJ Mag talks to Claussell about his remarkable history with Body & Soul, his musical philosophy, and how he’s trying to create deeper connections with his record shop and community centre

“Here comes the hose!” On a sweltering August Saturday in 1999, the Body & Soul party packed New York City’s Grand Central Park for a SummerStage concert series appearance, showcasing club culture’s connection to Afro-Latin sounds. Caribbean rhythms from performers Los Muñequitos de Matanzas and Jephté Guillaume pounded through the speaker stacks. Some 12,000 dancers swooned from the tar-sticky heat.

Suddenly, a jet of water shot from the stage and moved across the crowd, which joyfully threw its hands up in the air. Someone on the mic, rumoured to be eccentric NYC Parks Commissioner Henry Sterns, shouted, “Who wants to get soaked?” to a multilingual roar. Behind the decks were the Body & Soul founders, disco and remix trailblazer François K and DJ Danny Krivit; veterans of the 1970s downtown scene, at clubs like The Loft, Paradise Garage and The Roxy. At the turntables was their younger partner, Joaquin “Joe” Claussell, a musician and DJ whom they’d coaxed from his East Village record store, Dance Tracks, to play with them.

Claussell cut a striking figure, working the EQs with the passion of someone channelling an urgent, cosmic message. The three had launched their weekly Sunday afternoon party at Tribeca’s Club Vinyl in 1996, an instantly popular affair dedicated to a “melting pot of sounds”, which reached beyond the all-styles-and-smiles cliché to embrace decades of globe-spanning releases. They’d soon expanded to outdoor extravaganzas like this, featuring live bands and diva singers.

As the water hose made one final swing, the calliope triplets of Aztec Mystic’s just-released ‘Knights Of The Jaguar’ floated from the booth, deliberately pitched down to a swing-funk tempo, almost salsa-like. The dripping crowd caught fire again. This was quintessential Body & Soul: a deep-roots treatment of a cutting-edge Detroit techno record, by Mexican-American Underground Resistance member DJ Rolando, played for a vibrantly diverse crowd. Just the kind of thing that caused the New York Times to call the Body & Soul ethos, in a way that would spur a cringe today, “ethnic-tinged”.

“The concept of Body & Soul is that everyone loves everyone, and anyone can join in,” Claussell says over the phone from his Manhattan home. “It’s an egoless situation, about placing music and connection as the foundation of every party. When you tap into that overwhelming force that connects all of us through music, no matter who or what you are, as a DJ, you gain the freedom to play almost anything.”

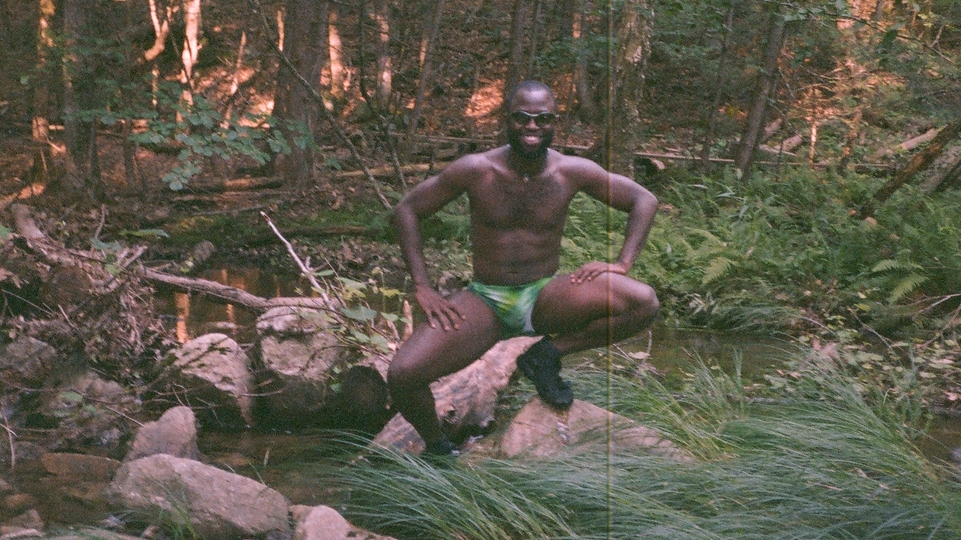

For Claussell, the SummerStage event was another divine step along a prolific creative path; one that equates music and dance to spirituality, drawing from an ancestral well of sounds. It’s been a fortune-starred journey, from a childhood immersed in his New York neighbourhood’s bustling music scene, to his latest album, ‘Raw Tones’; recorded on cassette tapes in pandemic isolation, and released this past month on the Rekids label.

Along the way, Claussell has become an avatar of soulful house: launching a storied label, reinventing the record store experience, and applying his organic, live-instrumentation production style to hundreds of records and remixes for the likes of Femi Kuti, Diana Ross and Herbie Hancock. “Everything I’ve done so far has happened naturally, as the result of someone — or something — suggesting or gently pulling me towards it. I never wanted to be a DJ or producer, I never considered that to be in my cards,” Claussell says. “For me, listening and dancing to music was enough. When I was out at Paradise Garage, I never looked up in the booth and thought, ‘Man, I really want to be a DJ’. It’s because of my deep love of, and trust in, music that any of this has happened. And that goes back to being raised in a home where music was considered sacred.”

A HOME FOR MUSIC

Claussell grew up in the Brooklyn neighbourhood of Park Slope, a name that’s now shorthand for upscale gentrification of the skinny latte and double-pram variety. In his youth, however, the brownstone-studded area was home to working-class Black and Latino families.

“It was a multicultural neighbourhood, so it had everything going on; even some things that were not accepted back then elsewhere, but are now. You could be gay or straight, whatever, it was beautiful,” he says.

Claussell’s Puerto Rican-French family — his mother and 10 siblings — trace their roots to the Yoruba people of Nigeria. Music, especially percussion, was a priority in their home. Joaquin’s older brother Larry was a drummer and leader of a Latin rock band, with a full Ludwig drum set and a state-of-the-art stereo system he brought back from an army stint in Japan. A metal aficionado, he got Joaquin hooked on Led Zeppelin, Jimi Hendrix, the Grateful Dead, Black Sabbath and Deep Purple. Claussell still has a soft spot for late ’60s and early ’70s psychedelic rock. Brother Jackie also had a stereo from army time overseas, and introduced Joaquin to American soul, spiritual jazz, and other, global sounds.

“My brothers weren’t just record collectors, they were record selectors,” Claussell insists. “They taught me how to discern music. We spent hours jamming or listening in our rooms. My mother played music constantly, too: Afro-Cuban, Afro-Latin, Top Forty, those classic Fania records.” Another brother, José, was a percussion prodigy who became the musical director of Puerto Rican legend Eddie Palmieri’s salsa orchestra.

From the hopping neighbourhood block parties led by brother Larry, it was a natural progression for teenage Joaquin to dive into the world of 1980s New York nightlife, moving to Manhattan where he soaked in different cultural scenes.

“New York was an incredible melting pot for nightlife then,” Claussell says. “I was a mod skinhead at the time, who went to CBGBs and the Mudd Club. I loved punk and the UK stuff coming out, like Depeche Mode and The Cure. I went to Paradise Garage for disco and house, and I would go to mainstream rock and pop clubs, too. I needed to fill my musical palette with every sound.” Claussell had dabbled in DJing, but after his main inspiration Paradise Garage closed in 1987, he hung it up. Walking home from his job as a high-end cabinet- maker a couple of years later, he happened upon the record store Dance Tracks, an East Village spot with a reputation for stocking rare house imports. Something drew him inside.

“I immediately got along with the owner, Stan Hatzakis,” Claussell remembers. “He left me in charge when he went to the bank, and when he came back, he saw that I had sold all these records. From that day we had a bond. I came on as the in-store DJ.”

Dance Tracks was a nexus of the New York DJ scene at the time, with greats like Frankie Knuckles, Deee-Lite, Larry Levan, Robert Owens and David Mancuso popping in to score future club anthems — as well as upstart youngsters angling to make a name for themselves in the burgeoning house and techno scenes. “I met some fantastic people, but unfortunately, I also witnessed egos and how the industry worked from behind my turntable,” Claussell says frankly. “I was happy just playing records. The rest of it didn’t appeal to me.”

Hatzakis had an artistic streak, and sparked what Claussell calls “the unexpected birth of my musical calling,” when he convinced Claussell to hop in a car to Long Island to visit one of his best customers, keyboardist Tony Confusione. Experimenting with “music collages”, their synergy quickly went beyond amateur fiddling; they produced two cult classics under the Instant House name, ‘Over’ and ‘Awade’.

“Those records magically emerged from our shared, deep love of house,” Claussell reminisces. “I had been watching how Tony and Stan were doing everything during that session, and they said, ‘Why don’t you do a version?’ I was nervous at first” — his production experience consisted of playing around on a Roland JX-8P keyboard and a Teac 3440A reel-to-reel — “but I had probably smoked a little weed, so I jumped in,” Claussell laughs.

That session was a harbinger of his future production style: tropical percussion over a driving beat, live instrumental solos tweaked with electronic effects, and wide-ranging samples that summoned global cultures. The Instant House tracks were released by New York’s Jungle Sounds Records in 1992; later that year, Claussell heard one of those tracks on the radio when he was in London visiting his girlfriend, and knew he was on to something.

But he wasn’t quite ready to devote himself to production. Instead, he concentrated on Dance Tracks, eventually taking over from Hatzakis and, along with partner Stefan Prescott, transforming the record store. Whereas most shops then were still barebones, aisle- oriented boxes, undecorated save for posters, Claussell looked to flip things into a lounge vibe. “We put in sofas, nice lighting and a full-blown system, so it felt like a club. It was, keep in mind, mostly men shopping in those days, so we had a nice place where their girlfriends and sometimes boyfriends could relax and hang out while the DJs did their thing. It made for a more family-like atmosphere. A lot of stores copied our model.”

The musical force guiding Claussell had plans for him beyond becoming a DJ’s DJ at a groovy record shop, though. He had noticed that, throughout the early ’90s, house music was becoming “harsher, more plastic, more pop”, and yearned for soulful sounds that celebrated individuality and history rather than collapsing cultural identities into a generic beat. And he had creative friends who would call on his talents for more ambitious projects.

“I don’t consider myself a DJ in the traditional sense... It’s not a performance or an act. I’m connecting to the voice of the Creator — whoever that may be — and feeding off the energy of the audience.”

BODY & SPIRIT

“Danny and François were regular Dance Tracks customers,” Claussell says of Krivit and Kevorkian, and the origins of Body & Soul. “It was always very humbling to speak with these DJs who had years more experience than me. I was actually shocked when they asked me to throw a party with them.” Claussell resisted at first. “I was content with what I had — turning people onto music, a dope soundsystem — but knowing then what I knew of François, his genius as a remixer, and that my first gig with them would be for a birthday party tribute event to Larry Levan, I recognised that this was a great opportunity that was not to be messed up,” Claussell laughs. “They convinced me. And it was beautiful, you know?”

This openness allowed the trio to create musical space for dub techno, Brazilian samba, Cabo Verdean morna, Punjabi folk, African-American gospel and extended odysseys like Nuyorican Soul’s ‘I Am The Black Gold Of The Sun’ and ‘It’s Alright I Feel It’. In the days before digital music streaming, Body & Soul sets and compilation CDs were messages in a bottle for an international queer, Black, and Brown audience that was eager to dance its way through the end of the grim AIDS era — and into a borderless club future that looked and sounded like their own histories and experiences. The compilations, released from 1998-2007, featured foundational Body & Soul tracks like Dubtribe Sound System’s ‘Equatorial’, Donna Allen’s ‘He Is The Joy’, and Cesaria Evora’s ‘Sangue De Beirona’.

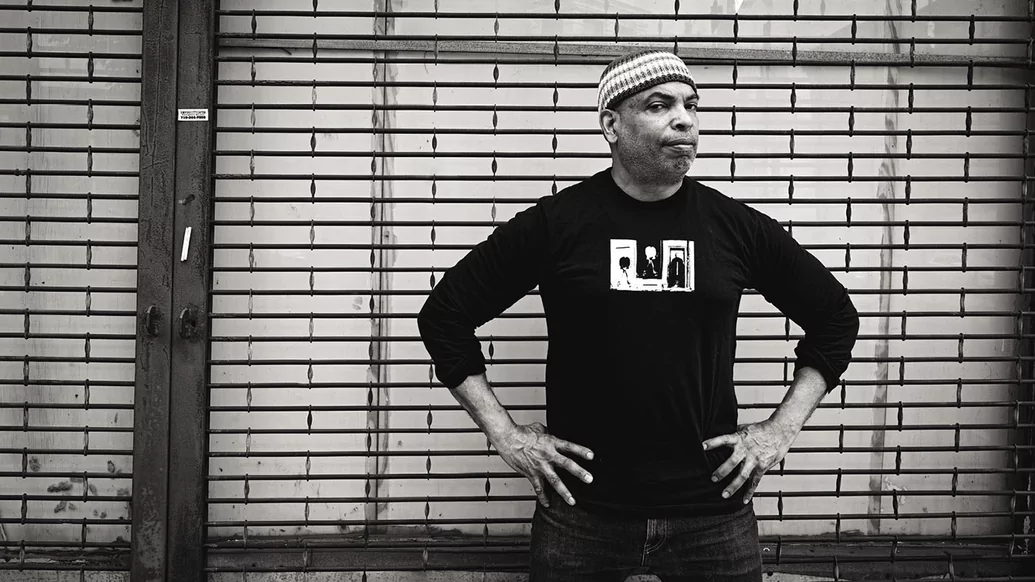

Claussell began attracting attention for his animated DJing, throwing his head back and riding the EQs, manipulating the music into something unique. For longtime house mavens, this is un-extraordinary, but as the internet has amplified his live sets to an unfamiliar audience, it has raised eyebrows (and comments).

“It’s a funny thing about my DJ style, I don’t consider myself a DJ in the traditional sense,” he says warmly. “It’s not a performance or an act. I’m connecting to the voice of the Creator — whoever that may be — and feeding off the energy of the audience.

“I think it has to do with how I grew up at home, where musicianship was held at a premium. When people are playing their instruments, they are speaking the language of music,” he continues. “I hear a lot of critiques of what I do out there, but it’s fine because being criticised is part of this whole thing. It empowers me. I know I’m sincere, and that there’s also a lot of people out there that really love what I do.”

Body & Soul launched Claussell’s public DJ career, and his production side was lighting up, too. “In the mid-’90s, it was getting harder to find records that reflected what I was doing as a DJ,” he says. Claussell started to lay the groundwork for his own label, Spiritual Life Music, which would focus on the organic feeling of house. But as the spirit would have it, he ended up launching two labels at once.

Claussell was planning to run his label out of the back of Dance Tracks when Jerome Sydenham, whom he had met when they DJ’d at chic downtown club Nell’s in the 1980s, approached him. Sydenham was hoping to start his own soulful house label, Ibadan, named after his hometown in Nigeria. He also worked as an A&R for Atlantic Records, which meant he had the “keys to the vault” when it came to the label’s artists. Would Claussell be interested in doing an “extracurricular” remix of one of Atlantic’s holdings?

Claussell jumped at the chance. The result was 1996’s ‘All Loved Out (Love Serenade)’ by Ten City, an exquisite 11-minute manifesto of Claussell’s production direction. “Ibadan wasn’t quite ready yet, and Spiritual Life Music was,” Claussell remembers, “so we released it there, and I thought, ‘Here we go!’” Ibadan was soon up-and- running; Claussell has released several records on the label. Spiritual Life Music has since put out more than 100 releases.

The early-to-mid 2000s saw changes for Claussell — the weekly Body & Soul parties ended in 2002 when Club Vinyl was sold, and he left Dance Tracks before it closed in 2007 — but he’s toured constantly since, and has released popular club records. His 2004 rework of Nina Simone’s ‘Feelin’ Good’ spawned a flurry of interest in the complicated idol, and 2018’s epic ‘Sacred Rhythm Mix’ of Cuban singer Daymé Arocena’s ‘Yambu’ chimes with his spiritual vision. On his ‘Africa Carribe’ series, he dives into the vaults of historic Latino music label Fania Records to “remix, remodel, and re-record” the music he heard growing up.

In 2010, Claussell opened a record store and community centre called Cosmic Arts, a hub for music, dance and art-making in Brooklyn’s Bushwick neighbourhood. Its purpose was to find deeper ways for people to connect over music than merely shopping for it. The centre usually hosts art exhibits, live music, healing drum circles and “cosmic dance workshops”, which hone “the practice of exchanging negative energy to positive energy, through movement and awareness”, Claussell says.

“We had to close our doors for a while, but we’re staying open as much as we can now. There are a lot of people that rely on Cosmic Arts. It’s a refuge, a place where people can go and call their home.” It’s been a natural outgrowth of Claussell’s vision of music’s power. But what happens to a creative life built on physical and spiritual connections when a pandemic forces you inside your apartment for months?

RAW TONES

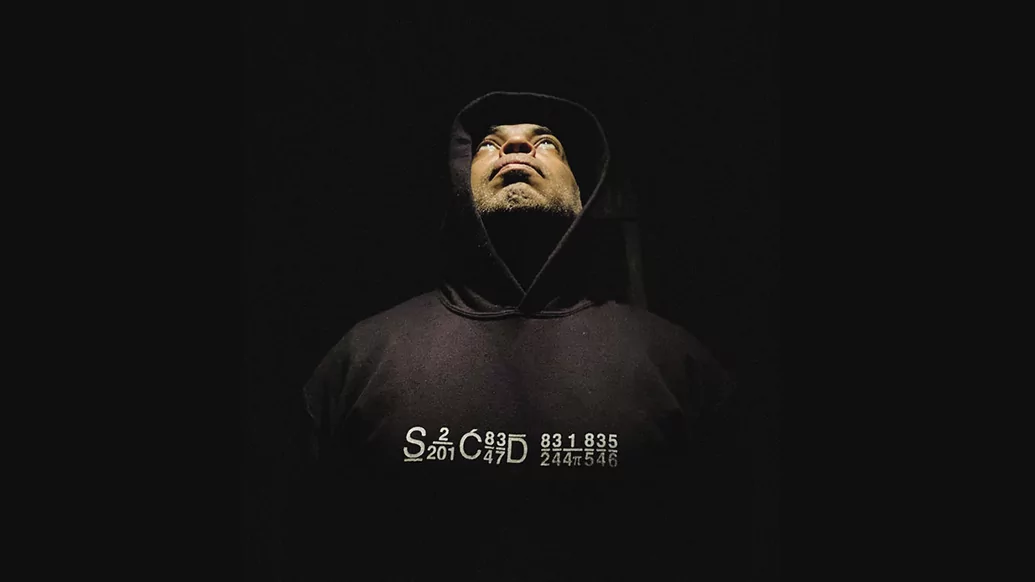

When Claussell was bored and angry during the lockdown, he dusted off his Tascam Portastudio and a case of Maxell XL-II cassettes, and recorded 50 tracks. Some of those tracks were released in 2020 through a cassette series on Sacred Rhythm Music, with screen-printed sleeves by Akemi Shimada — little sonic paper boats launched into the Bandcamp stream.

They caught the ear of Rekids label owner Radio Slave, who convinced Claussell to put nine of them out as ‘Raw Tones’. The album title is apt, but not because of production value — considering Claussell’s studio consisted of a four-track tape recorder, a drum-sequencer, a midi controller and a microphone set up in his living room, the quality of the compositions is astonishing. The tracks sound contemporary, with stretches of lo-fi charm and a stripped-down, electro-soul feel. The rawness is reflected more in the album’s directness.

“That had to do with what was in the air at that time,” Claussell says. “It was very dark, a lot of chaos and uncertainty; a very angry period during an unprecedented situation. To be honest, I’m still not at 100%. I don’t know anyone who is. I needed to put my head down and get into my creative process. On a track like ‘Break Free’, I wanted to obviously break free — this was some bullshit,” he continues. “On top of everything [with the pandemic], there was all this racism and craziness going on. My reaction is in those tracks.”

‘Break Free’ and ‘Mutha Fucka’ rear up with invigorating, tough-talk samples. But they’re still artful in a way that’s recognisably Claussell, if leagues away from polyglot calls for dancefloor unity. ‘Lock Down’ builds a blunt tension into the clangy beats, hovering synths and dissonant piano clusters, but a cosmic beauty peers through towards the end. ‘Blame Game (Table Top Idea)’ is politically engaged, sampling news reports of civil unrest and environmental devastation. Over it all, Claussell chants for us to “live a day without war”.

“You see on the news everyone blaming each other. Stop pointing fingers. Let’s ask ourselves: what are our roles in spreading negativity?” Claussell asks. “Let’s wake up to what we can do as individuals to change what’s going on out there. We never look at ourselves for things, we’re always blaming the other person. But we have a role in everything that happens to us.”

The album ends on a surprisingly lovely note with ‘Hallucinations Ejaculations’, which calls to mind early tracks from The Orb, invoking the group’s sincere, endearingly clunky optimism about Gaia, technology and the future. Could there be hope? At a time when we could use a global shot of positivity and a rush of spiritual connection, is the dance music industry equipped to provide?

“The crisis we’re having in the industry, and the world, is in the way we connect,” Claussell says. “Music is about spirituality and togetherness. I won’t say it’s been abandoned, because I don’t believe a lot of people recognised it was there in the first place. And I think the industry prefers to keep it that way. But we are spiritual beings. DJs like myself, Theo Parrish, Ron Trent, Jenifer Mayanja, to name a few — we thrive off connecting to the spiritual aspects of this music. That’s why I continue doing it in the way that I do it. I stay true to myself and my beliefs in all of this. And we need more of that. Especially right now.”