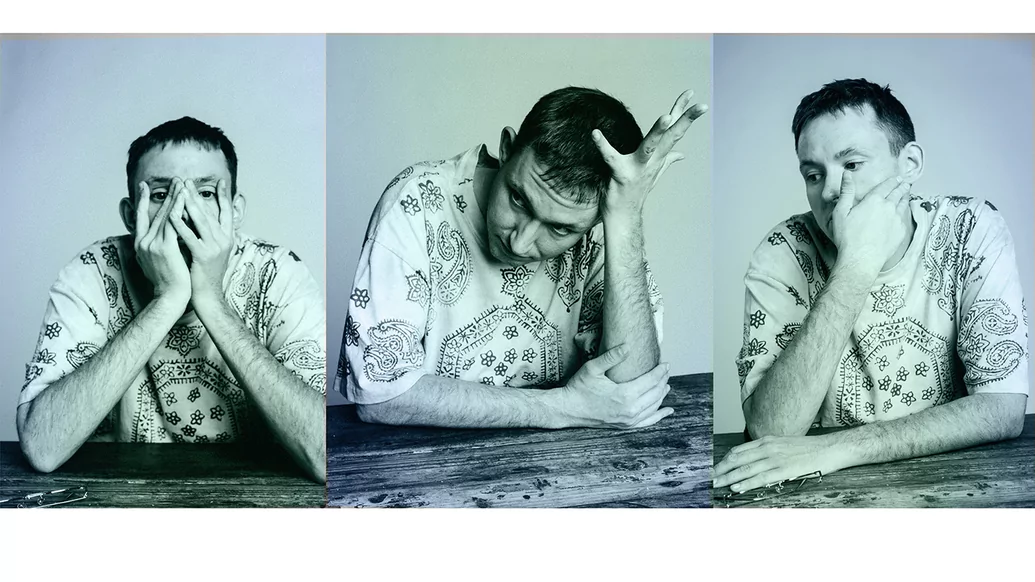

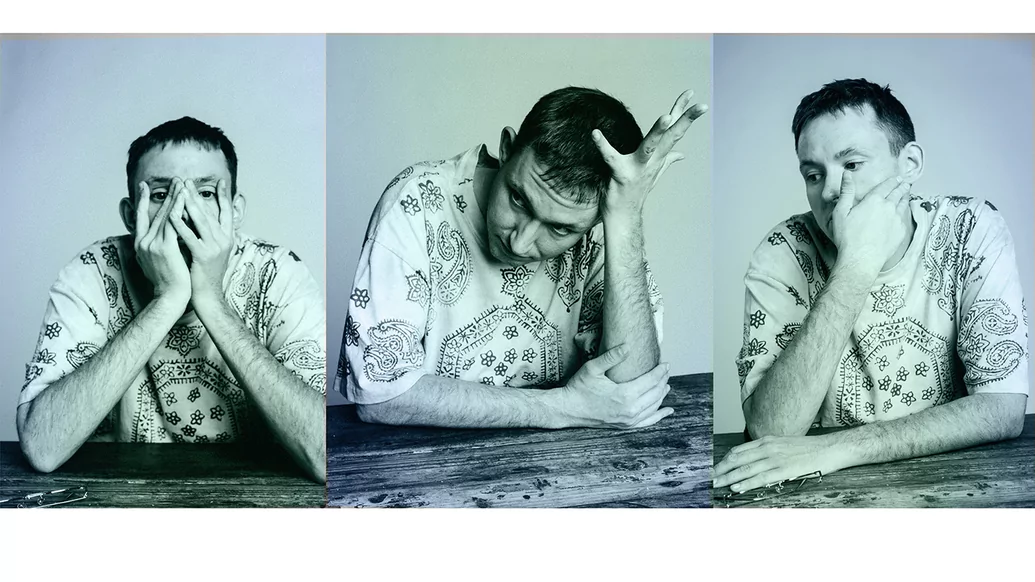

Hudson Mohawke: searching for euphoria

Hudson Mohawke is a mystery. The shy Glasgow-born, LA-dwelling producer and DJ has made boundary-breaking music and worked with superstars, but he scarcely does interviews, leaving his music to do the talking for him. But the pandemic lockdown has led to a shift in his consciousness of late — and a thrilling new archive album series for Warp Records. As Amy Fielding discovers, Hudson Mohawke is ready to tell his story, and share so much unreleased music with the world

It’s a hot August morning in Los Angeles, and the sun is beating through the open door of Ross Birchard’s home studio. He smiles and speaks animatedly, against a backdrop of wooden walls adorned in posters and surrounded by synths and cables. As we chat about our weekends, he sips an iced coffee. He looks younger than his 34 years and his laugh is infectious.

Ross Birchard is better known by his artist name, Hudson Mohawke. A founding member of Glasgow’s LuckyMe collective, he’s spent the last 12 years producing experimental electronic music: largely on Warp Records, part of the roster alongside Aphex Twin, Boards of Canada and Squarepusher. In recent years, he’s broken into the world of commercial hip- hop and pop production, most prominently for Kanye West, but also for Pusha T, Drake, FKA twigs, A$AP Rocky, Frank Ocean and Anohni, among others.

While his work has become increasingly high profile, operating in a world of superstar hitmakers, Birchard remains a private and shy individual, who finds comfort in an Internet-dwelling gallows humour and a childlike love for shock and wonder. It’s a humour that, in large part, has inspired who we recognise as Hudson Mohawke.

It began with his mutual teenage obsessions with happy hardcore and ’90s hip-hop, devouring DJ mixtapes online. Through his PC screen, genres bled together and ideas were sparked for his own DJ sets, where he’d mix happy hardcore’s caustic melodic riffs with hip-hop’s rapid-fire, sample-fusing turntablism. His obsessing paid off, too. In 2003, at just 15 years old, Birchard was a finalist at the UK’s DMC Championship, then the youngest in its history.

Around the same time, he began producing his own, boundary-shifting music using Fruity Loops, the software he still uses today. Those years spent consuming electronic music online, with little in the way of lived context, fuelled the sparkling strangeness of his beats — as if made in a cocoon, with no outsiders to bother him with ideas about the “right” or “wrong” way to do it. And when it came to sharing those beats, he was using MySpace: uploading short, low-quality audio clips of experimental loops, and sketches of ideas, with fantastical names and silly jpegs as artwork placeholders; uploading directly to whoever cared to listen, whenever he felt like it.

The Internet was how Birchard built his early fanbase, and how he stays connected to many of those same listeners today. But in the mid ’00s heyday of MySpace, the Internet was also a vast plain for producers like Birchard; optimistic and freeing, blurring the lines between experimental underground music cultures and a youthful, file-sharing Internet culture.

This August, Birchard shared ‘B.B.H.E.’: a 14-track album of archive material, and the first release of an ongoing series for Warp; some of the oldest tracks on ‘B.B.H.E.’ were made in that early ’00s period. A few weeks later, he released another album, the 13-track ‘Poom Gems’, in the same spirit — and there’s still more to come.

The series sees Hudson Mohawke the producer at his Technicolor best, and it seems that his long-time fans are the most excited about it: once-lost and hitherto unidentified tracks, obsessed over on YouTube comments sections and Reddit subthreads, are finally being tracklisted. The series also reads as Hudson Mohawke’s final, most playful form: volumes that track his evolution as a producer, a Pokémon-style levelling up of characters, growing into their biggest, boldest selves.

"Music like happy hardcore is very direct and pure, an expression of joy. Who the fuck is anyone to say that something that evokes the human emotion of joy is cheesy, or not cool?”

Euphoria

While other great instrumentalists in his vein of experimental hip-hop have their own sonic signatures — The Neptunes’s inimitable drums, Darkchild’s sparkling strings — Hudson Mohawke’s signature seems less about technique or easily identifiable production motifs. It’s about euphoria, presented through fizzing synths and progressive percussion. In one breath, it’s music made for video games, neon cars in dark cities, and the garishly-painted Waltzers ride at the small town carnival. In the next, it’s the backbone for some of the decade’s best rap tracks, or an unforgettable moment on a club dancefloor, synapses snapping at lightning speed.

Birchard makes no secret of the fact that his aim, with all his music, is to invoke euphoria. “I’ve always tried to incorporate a sense of joy into what I do,” he says. “I think that, for one reason or another, a lot of people think that’s not a ‘cool’ thing to do in underground music, or something? Music like happy hardcore is very direct and pure, an expression of joy. Who the fuck is anyone to say that something that evokes the human emotion of joy is cheesy, or not cool?”

Even in the early days, he was determined to find a way to bring this unabashed attitude towards euphoria into a commercial production sphere. He loved the sample-based loops and grooves of Four Tet and Madlib, and the heady MPC patterns of Just Blaze, but his favourite producer was Timbaland. “On the face of it, Timbaland’s stuff is commercial music, but it’s also very intricate and well-produced, just genuinely great music,” he reflects.

“I was really interested in how you could re- contextualise that production mindset by bringing in weirder influences and sounds [from electronic music]: playing with the sentiment, ‘Well, on paper, this is super commercial’, but when you frame it with different reference points it becomes an entirely different thing; like how an instrumental loop can also be a great club record, depending on the party. That was a big inspiration for me. I’m always trying to find that sweet spot.”

Birchard has DJ’d for longer than he’s produced. When LuckyMe started, micro-scenes of electronic music were taking off in Scotland, but specifically in Glasgow, where line-ups at smaller, DIY parties weren’t necessarily restricted by genre. “Whether it was myself, Rustie, Jackmaster or the Hessle Audio guys, when they were breaking through, we were all doing different stuff but playing at the same parties, and you could see this throughline in having us all together,” he remembers. “I know every UK city has their own little club-nights which are super grassroots, but ours were good fucking parties with minimal bullshit.”

“The first hour of an Optimo party would be weird soundtrack records, poetry and other shit, into punk and techno — and then it’s fucking super party mode. By the end they’re playing Johnny Cash and everyone is crying."

Optimo

His attitude comes from his time on the dancefloor as much as his time in the booth. He cites Optimo’s fearless approach as an influence. “I don’t even think that Optimo are an influence in the sense of ‘I love everything they play’,” he says, “but their approach to DJing and how to put together a party — to this day, I’ve never experienced anything like it.” He describes the flow of a quintessential Optimo night as “unhinged”. “It’s the thought process of, ‘I’m gonna play a punk 7-inch, then a gabber record, then a 78rpm opera record from the 1920s’,” he explains.

“The first hour of an Optimo party would be weird soundtrack records, poetry and other shit, into punk and techno — and then it’s fucking super party mode. By the end they’re playing Johnny Cash and everyone is crying. You feel the full spectrum of human emotions.” He laughs and shakes his head. “And to host it on a Sunday night, when people have work the next morning? It was this intense sense of community. I don’t know the PC way of phrasing this, but it was very anti-c*nt. If you’re a c*nt, you can just fuck off.”

After becoming a regular on the Glasgow club circuit and releasing a string of EPs on LuckyMe, Birchard was accepted into the Red Bull Music Academy in 2007. He flew to Toronto to take part, where he also met Steve Beckett of Warp Records. He signed to the label as Hudson Mohawke the following year and, in 2009, released his debut solo album, ‘Butter’.

The album is considered a game-changer: 18-tracks of euphoric melodies, glittering synths and licks of ’90s R&B, with hints of EDM and trap. Birchard knew when he released it that ‘Butter’ was ahead of its time. Even the ’80s-inspired, thrash-rave artwork, designed by Glaswegian visual artist and producer Konx-Om-Pax, is a statement in itself.

“It’s a strange experience to make a debut on Warp, and to be honest, it’s the same with a lot of things I’ve done. A song comes out and people are like, ‘This is alright’, but then four or five years later they’re like, ‘Shit, I really like this!’ There were obviously people who liked that record when it came out, but people didn’t start talking about it in a wider sense until much later.”

The album did get interest from commercial artists, with Rihanna’s team reportedly looking to take on album highlight ‘Fuse’. But despite the attention, Birchard kept all of the tracks intended for ‘Butter’ to himself. Maybe he knew that such offers were an early sign that his search for that sweet spot was moving steadily forward.

Birchard’s subsequent release, 2011’s ‘Satin Panthers’ EP, saw him praised by Jay-Z’s long-time producer and one of his heroes, Just Blaze. ‘Satin Panthers’ vaults between tempos and genres at breakneck speed, and even samples British pop singer David Grant’s 1983 hit track ‘You Are All’ at one point. It’s ‘Thunder Bay’, though, that leaves the lasting impression. DJ Mag recounts a moment when, at last year’s Sulta Selects party at Printworks in London, Denis Sulta shook the walls with its gargantuan basslines. Nearly a decade after release, tracks like ‘Thunder Bay’ still have an immense, visceral power.

Birchard nods warmly — he still loves ‘Thunder Bay’ — and reaffirms his keenness for keeping versatility and diversity at the forefront of his beatmaking. “I always want to try a lot of different shit, keep learning and stay open-minded,” he explains, “and not making shit just from templates, or within the parameters of what that genre allows — ‘rules’ in that particular scene, you know? If you have your own MO, you can play around with it.”

Collaborative

Among all this solo work, Birchard established another alias — the collaborative side-project TNGHT, alongside Canadian producer Lunice, which they debuted in 2012 with a self-titled EP. TNGHT tore through the clubs with a bombastic swagger, loudly enough for the mainstream to hear it. ‘Higher Ground’, from the self- titled EP, was used to soundtrack adverts from Under Armour and Adidas, introduce NBA teams in stadiums and embellish a freestyle by Kendrick Lamar.

In the heat of this moment, Birchard got an email from a then-unknown Virgil Abloh, who was acquiring behind-the-scenes production talent for Kanye West’s G.O.O.D Music label. “I remember getting the email and thinking it was bullshit: ‘This looks like spam’,” he laughs. Virgil was legitimate, though, and soon after, Birchard started working in the studio for Kanye West, with production credits alongside names like Mike Dean and Mike Will Made It on Kanye West’s Grammy- nominated 2012 track, ‘Mercy’.

Aside from his work with Lunice as TNGHT, up until this point, all of Birchard’s productions had been solo efforts. Now, he was working alongside dozens of other musicians, songwriters and producers, navigating a totally new music-making domain. Past collaborators have hinted that the studio experience within G.O.O.D. Music is eccentric and nonlinear, with a hands-on, magpie-esque approach to selecting the best moments for each track. For the first time, Birchard’s ideas were being picked apart and fine- tuned not just by himself, but by a like-minded team of creatives.

Ultimately, he worked with West on his 2013 album ‘Yeezus’, and is credited as one of several producers on tracks ‘I Am A God’ and ‘Blood On The Leaves’; the latter samples TNGHT’s cacophonous ‘R U Ready’, from that first, self-titled EP. “Working with those guys was when I found that sweet spot between what’s commercial and what can be more interesting on the production side,” he says. “I saw that it is possible to do that on the highest level.”

Before being in the studio with rap titans, despite his affection for producers like Just Blaze and Timbaland, Birchard admits that he had no idea about the commercial production process. But he was determined. “It’s really important for me to stay in the mindset of feeling like you’re the least experienced person in the room,” he says candidly.

“Within that world, it’s very easy to get full of yourself, and often when that happens — and I've been guilty of this at points — you become less open to trying new things. In embracing this notion of ‘I’m a big fucking deal’, you're limiting yourself. You stop absorbing, stop learning new things, and that’s just not specific to music. When there’s a lot of people blowing smoke up your arse, that’s where you’re like, ‘I don't need to keep learning, fuck that’.”

Imposter Syndrome

Along with new studio practises and creative challenges, there’s the human element, too. When Birchard became immersed in this new world, somewhat inevitably, it became overwhelming. Although he wanted to live as closely to the music as possible, the lifestyle that came with it was an unknown territory, far removed from his comfort zones of DJing in dark basements and diving into Internet wormholes for laughs. Imposter syndrome started to kick in, hard.

“There’s only so long you can pretend you’re that kind of person, and I’m seriously not at all,” he says, laughing and holding his hands up in confession. “I’m shy and reserved, that’s who I am — until I’d have a bottle of Hennessy, that is.”

“A little bit after that period, I decided to go sober,” he says candidly. “Although I had some pretty gnarly experiences, I’m going to preface that by saying that everybody’s heard the sobriety sob story. It’s not something that I shy away from or try to hide. It’s a part of me. But there’s also nothing special about it, and a lot of people deal with that shit. It’s not fucking glamorous and it’s not a big news story — it’s just pretty sad.”

Birchard was busy touring with Lunice as TNGHT, and under pressure working in the studio producing for other artists. After a pause, his tone becomes sombre again. “I feel like if I had been still going during lockdown, then fuck-knows what would have happened to me. That’s the exact time in your life when you’d just be like, ‘Fuck it, let’s go’.”

He didn’t let it all go, though. While working on his sobriety he continued to produce for other big names, and a slew of new music that reframed him as a solo producer. In 2015, he dropped his second album, ‘Lantern’, on Warp Records. A refreshing sugar rush with booming kick-drums and uplifting chords, it showcased a newly refined, hi-resolution version of Hudson Mohawke. Digitalising tracks from the ’70s like D.J. Rogers ‘Watch Out For The Riders’, and nodding to happy hardcore with a Darren Styles sample, the time he’d spent with G.O.O.D. Music shines through on ‘Lantern’, while holding onto the tongue-in-cheek, euphoric energy of ‘Butter’. In the five years between ‘Lantern’ and ‘B.B.H.E.’, Birchard remixed and produced for a string of award- winning names, soundtracked the PlayStation game Watch Dogs 2, and rekindled his work with Lunice as TNGHT, with their 2019 album, ‘II’. The TNGHT comeback set the Internet ablaze, and they announced the return of their live show in 2020.

With renewed momentum behind them, 2020 looked set to be a bright year for TNGHT, and for Hudson Mohawke. That all changed with the COVID-19 pandemic. After mentally readying himself for a year of travelling and performing, Birchard found himself at home, in an intense period of reflection; looking to his past and spending time in the studio, and on the Internet. Birchard’s tone becomes more serious when we inevitably talk about the upheaval the pandemic has caused.

“I’m always grateful for that [focus],” he says, about being stuck at home, “but this is a weird situation and everybody’s going through some serious shit. Even if, on the surface, it seems like things are somewhat stable, deep down it’s still a pretty traumatic experience for everybody.”

“There’s nothing insanely wrong with me hoarding tunes, but when you’re faced with something like a pandemic, where we’re at home thinking that we all might die, keeping old tunes just pales in significance."

Pandemic

The pandemic has made people nostalgic, pining for a sense of comfort and familiarity. While listeners are scrolling through social media and streaming platforms, seeking out moments of joy in new releases, mixes and live-streams, artists are also trying to find ways to reconnect with their audience in new, exciting ways.

Birchard wants to give his fans those moments of joy: those bursts of intense, euphoric nostalgia, that in turn guide his music-making. He recounts a rare highlight from lockdown, laughing in near disbelief. “Lunice and I actually played a virtual Minecraft festival,” he says, explaining that it was the perfect backdrop for TNGHT’s weird, abrasive beats. “It was so strange and funny. You’re literally standing in a virtual DJ booth, looking down at the CDJs, thinking, ‘What the fuck is going on?’ When you’d ‘teleport’ to the ‘green room’, and go to a bar to buy drinks, it made your screen shake. It was great, it was such a good concept.”

Tapping into that playful spirit, and with the fans in mind, the archive album series for Warp, then, feels like Bichard’s most personal project to date. The process of collating tracks for the series has been a happy distraction. “It’s been one of the slight silver linings of lockdown, getting to spend more time here than I would normally,” he says, gesturing to the studio. For the track selection process, he spent much of his time recovering files from lost or battered hard-drives — each rare find and recovered snippet a precious gem — and deciding which of his long-secret files to let go of.

“I’ve had this music sitting around for a long time — thinking that too much time has passed, or that it’s not worth doing this kind of release,” he says. Much of it came down to a snobbery around identifying unreleased material, he admits, “a little culture of ‘You don’t get to have this, and you only get to hear that if you come to a show, because no-one else gets to have this or play that’.”

He laughs at himself, thinking about how he held onto this attitude for so long. “There’s nothing insanely wrong with me hoarding tunes,” he says, “but when you’re faced with something like a pandemic, where we’re at home thinking that we all might die, keeping old tunes just pales in significance. I asked myself, ‘What am I gaining from sitting on material that people clearly have been asking to hear properly for years, and are being forced to listen to bad YouTube rips of?’”

‘B.B.H.E’, by the way, stands for Big Booty Hiking Expedition. It’s a nod to his love for meme humour, with ludicrous cut-and-paste artwork and screamingly loud colours. The music is full of moments of ludicrous and loud moments, too: of light and dark, darting between tempos; enchanting melodies conjured from the depths of his adolescent bedroom. ‘B.B.H.E.’ sees Birchard finally open the doors to a tightly-locked vault.

The series isn’t structured chronologically, and the track selections span nearly two decades. One unheard, Four Tet-esque contribution, ‘Tar’, was made back in 2005, and ‘100HM’ has been doing the rounds on YouTube since 2013, after being featured on Grand Theft Auto V through one of the in-game radio stations, FlyLo FM. One track in particular, ‘Monte Fisto’, has been eagerly anticipated by fans for years. Featured on an Adidas television advert with Lionel Messi in 2013, the larger-than-life anthem was never officially released, instead passed around online in low-quality, two-minute MP3 files.

It’s tracks like this that Birchard feels he needs to share with fans directly. It’s telling that the series hasn’t had a formal album release campaign led by Warp. Instead, each album is uploaded by Birchard to Bandcamp, and tweeted out from his own account, with accompanying, suitably silly artwork. “I think it’s because I’m coming originally from that era of Myspace, or to some extent even SoundCloud, where you’re very connected to the release,” he says.

Directness

That affinity for digital directness finds some common ground between Birchard and how other, big electronic names have operated in recent years. In early 2015, Aphex Twin uploaded over 100 unreleased tracks and demos to a SoundCloud page for “user48736353001”, with little warning or fanfare — the news spread online like wildfire, with fans of the pioneer scrambling to share and talk about each new upload in real-time. When it comes to more contemporary work, established producers like Four Tet and Actress have been sharing their new music directly with fans, tweeting out links for releases and artwork with a refreshing unfussiness.

Though Birchard’s archive album series is on a legacy label like Warp Records, it seems to fit happily with this style of self-publishing. “When I started this project one of the things I said to Warp was: ‘Yes, we’ll do this as a Warp release, but I want it to really feel like it’s directly coming from me’. I don’t like to be too removed from that process.” Speaking about what the series must mean to his fans, Birchard scoffs at himself, shaking his head. “I love that people would take the time to make some compilation of weird rips [of my tracks] from who knows where,” he says. “That’s amazing, but the only reason they need to do that is because I’m being a c*nt about it and not releasing them. So why not just fucking have them?”

The second album, ‘Poom Gems’, or as he recently tweeted, “more unreleased shit that it’s about fucking time was available properly”, is another, euphoric 13-tracker. There are nods to hardcore rave on effervescent closer ‘Things You Do’, and another YouTube favourite in the form of ‘Solstice Izo’, all twinkling piano runs and rippling thumps of bass. There’s also a flurry of tracks across both albums that feature in his 2019 mix for Warp’s 30th anniversary, and the scrapbook mentality of the series reflects his more recent mixes and sets, which largely consist of his own, unreleased material, sequenced in bursts as short and sweet as the tracks themselves.

As much as the series is a way for Birchard to give back to his fans, it’s also a way for him to clear the air, and his hard-drives, before trying something brand new. “Part of my thinking is that I have a lot more music that’s going to be released next year,” he says. “These albums are of music that I’ve played on various radio shows, in mixes, or that people have ripped from YouTube, so it’s all floating around out there, but there’s not been a very clear lineage of what I’ve been working on lately that people can clearly follow; to see throughlines between this,” he says, threading his fingers together in a web, “and that. It’s important to have a throughline in my albums, and it’s something that I would have never sat down with, and really thought about, without this year, without lockdown.”

Just before this year of change, he released a single with Turbo Recordings boss Tiga, ‘Love Minus Zero’, which saw him tap into happy hardcore again: “just unashamed, honest stuff that feels nostalgic without being retro, and captures that naïve, joyous energy, you know?” That same feeling bolts through other recent releases — ‘Black Cherry’, a sought-after banger from EA’s FIFA20 soundtrack, and ‘Heart Of The Night’, an EP of dreamy R&B bootlegs.

Now that lockdown restrictions have eased in Los Angeles, he’s back in the studio collaborating with vocalists, too — ‘Rooted’, the latest single from US R&B powerhouse Ciara, came out in August, and he’s been working with flamboyant rapper Azealia Banks. Even with this new momentum, and with years of star-studded work to his name, Birchard is still shy and private. “There’s an element of Scottishness to it for me,” he says, “where you’re very reluctant to blow your own trumpet, you know?

“If there’s something like that I’m not comfortable with, I just won’t do it. It’s not even necessarily that I hate the concept of being famous. It’s that it’s just not me, it’s even to my detriment. I’m not screaming about the stuff that I’m working on because of it. It may sound naïve, even now, but I genuinely believe that if you’re making good shit, it finds the right people.”

As the archive album series rolls on, we can agree — when it comes down to it, great work speaks louder and clearer than anything else.

The latest edition of DJ Mag is on shelves now, and available to buy online here.