How Ultra Naté's 'Free' became a dancefloor anthem for personal liberation

Ultra Naté’s house anthem ‘Free’ went from club anthem to international pop hit in the late 1990s. Broken by Louie Vega at the 1997 WMC, it was adopted by the LGBTQI+ community and elevated into charts worldwide. DJ Mag talks to Ultra about the genesis of this enduring dance classic

It's precisely 9am in Baltimore. Ultra Naté — her real name — is raring to go. “It's not super-early,” says the super-professional 53 year old. She is so immaculately turned out it's as if she's just about to step out on stage.

Behind her is the best Zoom background we have ever seen: a wall of framed gold discs, No.1 singles and Billboard Music Awards. “That's not even all of them,” she laughs. In fact, she has had at least one Top 10 single in each of the last three decades and isn't done yet. “I'm always working towards the ultimate goal. And my ultimate goal is my 10th album.”

Ultra is utterly engaging, infectiously upbeat and full of positivity. Even so, she admits there were “very scary aspects” to the last year, such as dealing with homeschooling her 15-year-old, health concerns and feeling like “there's this cloud outside your door that could make you extremely sick, or actually pass away”. She lost a lot of friends to Coronavirus, so she focused on creating a routine for herself in order to stay afloat. Part of that included continuing to host her own 18 year old Brown Sugar events — socially distanced, of course — in Baltimore. But she also worked out a lot.

“Even if I was just doing like a YouTube program, or a bar or HIT routine, or just something, even on my most non-motivated days. I knew that keeping some sort of fitness routine would get the endorphins kicking in and hopefully offset that really sad depressive energy that was going on,” she says. “I was doing a lot of hacks on myself."

In the last year, like the 30-odd before them, the American has also remained deeply immersed in music. “I've always been in some state of writing music, whether just individual songs or with a definitive project in mind, even if it hasn't fully crystallised.”

Watching the Deee-Lite-inspired, retrotastic, ’70s styled video for her latest single 'Supernatural,' you'd be hard pushed to know which decade it was made. Musically, it's a throwback to her early house sound. It's a devastatingly simple but effective track produced by the Funk Cartel with a dusty ‘90s groove, playful flute and trumpet hooks and, of course, Ultra Naté's trademark belting vocals. Interestingly, like her earliest hits, it has also been signed by a UK label, this time BMG/Skint.

Staying fit and healthy is something she has been conscious of for many years. As a young woman in the ‘80s, Ultra spent much of her free time dancing for hours on end in all the local Baltimore clubs. “All I was interested in was music and dancing, none of the other extracurricular activities that were going on,” she remembers. “But I fell in love with sound system culture, underground culture, with that setting.”

All that dancing kept her fit and healthy, but as soon as she had musical success and started touring, that changed. Suddenly she was snatching junk food on the road, not resting properly, too tired to exercise. "I gained weight by the time I was getting ready to start my second album," she says. “And at the time, I was on Warner Bros. They told my manager to have a conversation with me. Basically, he had to say I was getting too fat.”

It's unthinkable that would happen in 2021. As is being asked to change your name, which Warner also tried for a while. But as someone who grew up listening to the tightly stylised acts on Motown, Ultra understands why they did it back then. “My feelings were hurt in that moment. But I was signed to a major label, they have a certain look that they wanted me to have. And I was like, ‘OK, well, I can meet them in that place’. I hired a physical trainer and he taught me so many amazing things about nutrition and fitness that I've pretty much carried on throughout my life."

It’s on those pre-major label early dancefloors that Ultra befriended production trio the Basement Boys. They were already making music and persuaded her to get in the studio one day and start singing. At the time, she was actually studying medicine. She had long been listening to artists like Marvin Gaye and Boy George but had no plans to get into the industry. "I was working on music as a fun creative thing that I had never really tried before. But they kind of talked me into giving it a whirl. I really had nothing to lose. So I did it. There was no thought process like, ‘Oh, I'm going to be a singer. I'm going to be a songwriter’. It just happened.”

It happened because the Basement Boys already had links to A&R Cynthia Cherry, who had just joined Warner Bros UK. She liked what she heard and signed them all. Two albums followed — 1991's ‘Blue Notes In The Basement’ and 1993's 'One Woman's Insanity’. Listening back now, they perfectly fit in with the crossover house sounds that were dominating UK charts. But when Cherry moved back to the States, the garage house sound didn't translate as well so the label tried to steer Ultra towards a more commercial sound.

“The US system didn't get what we were doing as a dance act that came from garage, underground music culture. They wanted us to do pop-dance kind of music. We tried to meet them in the middle but we also didn't want to alienate our underground fan-base, so we came up with ‘One Woman's Insanity' as an album that suited both those places. But it wasn't enough, so we made the departure.”

Turns out, it was the best thing that could have happened. After consulting with her manager, Bill Coleman, Ultra decided she wanted to carry on with music. “It was a fork in the road moment. Bill and I really sat down and had a lot of conversations about the next move. We decided it was time for me to move on in terms of style of production. It was time for me to be completely independent, as an artist and songwriter, to broaden the types of songs I was writing.”

After making that big decision to “jump off a cliff” and “re-bake the cake”, Ultra left the safety of the partnership with Basement Boys and started working with other writers and producers, working on the next album even though there was no deal in place. It was Bill who suggested Ultra worked with legendary house duo Mood II Swing, aka John Ciafone and Lem Springsteen. She admits she had no knowledge of their status at the time but soon came to love their sound. “It was so tight and concrete and sonically on-point,” she beams. “As well, they wrote beautiful songs that sound good on the radio, so when we got together it was just really love at first sight.”

A label deal with seminal New York label Strictly Rhythm, to which Mood II Swing was signed, followed. It was a perfect move that gave Ultra the freedom to do what she wanted. Going to another major didn't make sense at the time, but neither did going to an independent that didn't have brand recognition, didn't have the infrastructure to build a record quickly and blow it up. “Strictly had a history of working records, building them on the club level, then through radio and over to the mainstream. And most importantly, you know, paying people like they're supposed to be paid was a really big deal. All those things played into our decision to sign with Strictly."

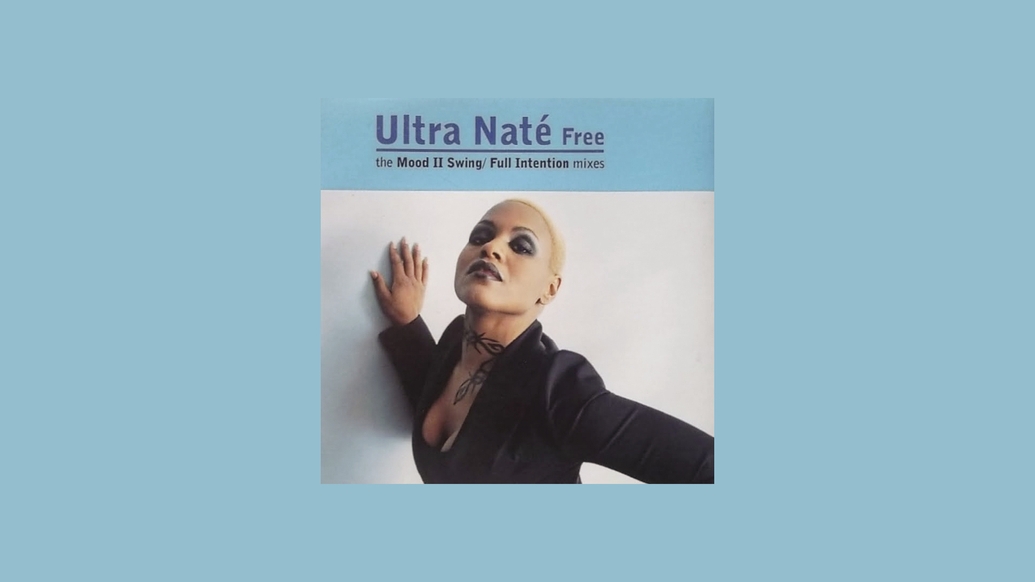

It quickly proved a perfect partnership, with Ultra's defining mega-hit 'Free' arriving in early 1997. At the time, female-fronted house acts were everywhere, but this track stood out. First of all because of her vocal performance — she doesn't just sing the chorus, she rockets it into the stratosphere with infectious passion and burning soul. Of course, the simple but empowering message to be yourself and “do what you want to do” is also relevant to everyone on the planet in some shape or form. And so it proved, as the tune became an anthem on the LGBTQI+ scene and even recently made it back in the headlines when Yousef and Fatboy Slim played it at the Circus Covid test-event in Liverpool.

“That was quite amazing,” smiles Ultra. “It was chills, it was literally chills, to see younger people reacting. And that's the beauty of it, how this music transcends generations and becomes a part of their lives. That's really for me the biggest power in this industry because it's a tough business to be in. You know, it's a rollercoaster, mentally, emotionally, physically, financially. You have to be able to roll with the punches, take the ups and the downs. But whenever you question what you are doing, and why you are here, having moments like that really reinforces it and speaks to the higher power. It's not just about yourself, it's about the thing you're putting out there that becomes empowering to other people.”

‘Free’ came about after another discussion with manager Bill. Dance and garage had changed since Ultra's early hits like ‘It's Over Now’ in 1989, ‘Joy' in 1993 and ‘Show Me’ in 1994. “We didn't really want to do what we had done before and do straight-forward house,” she says, adding: “The label trusted us, we had done major label albums before, so they gave us a blank cheque to do what we wanted." So, with Lem and John, the team drew on their other influences such as rock, alternative and gospel.

Once it was decided they were going to experiment with a rock kind of vibe, Ultra gave the producers REM's ‘Losing My Religion’ as a reference. “I loved the way that the guitars really feel bittersweet, like melancholic when it starts. I love that when you hear that first guitar on ‘Free’, it immediately just grabs you. It's iconic in and of itself. And so that was what we started with as an idea.”

“We just wanted something that would speak to everyone's heart and soul. Because there's something every person wants to be emancipated from in their lives, whether it's out loud or on a personal level, whether it's an addiction, love for someone that's not reciprocating it, or just not feeling appreciated.”

The famous riff was played by Woody Pak, a friend of Springsteen, and the team spent “many hours in” and “a lot of money on” the studio to get it all right. As for the lyrics, Ultra just “vibed to the melodies” and came up with a sound, then worked backwards on crafting the chorus, the bridge and the verses, all building the story towards the huge moment of release.

She credits her “secret sauce” as being her long-time vocal producer Danny Madden, who she has worked with since the Warner Brothers days. “I wasn't a singer by trade, and I didn't really know my voice or what it could do, so I was just winging it a lot of time, but Danny taught me so many things.”

With a stadium-sized setting in mind, Ultra says, “I always remember Danny clearly saying, 'Let's go, just do what you want’. I liked that, so we just took that idea and really expanded on it. We didn't target anyone specifically with the lyrics. We just wanted something that would speak to everyone's heart and soul. Because there's something every person wants to be emancipated from in their lives, whether it's out loud or on a personal level, whether it's an addiction, love for someone that's not reciprocating it, or just not feeling appreciated. Hopefully, the track gives you that momentum, that push, baby bird, to just fly out of the nest, you know?"

Louie helped it become a club smash, and it was only a matter of months before it became a crossover radio hit and went on to truly global chart success. Now, it has made it into Best Dance Singles Ever — or thereabouts — lists by everyone from Rolling Stone to the Guardian, NME to DJ Mag. The UK, in particular, loved it, and Ultra performed a number of times on Top Of The Pops, and the video was played on a near hourly basis on MTV throughout the year.

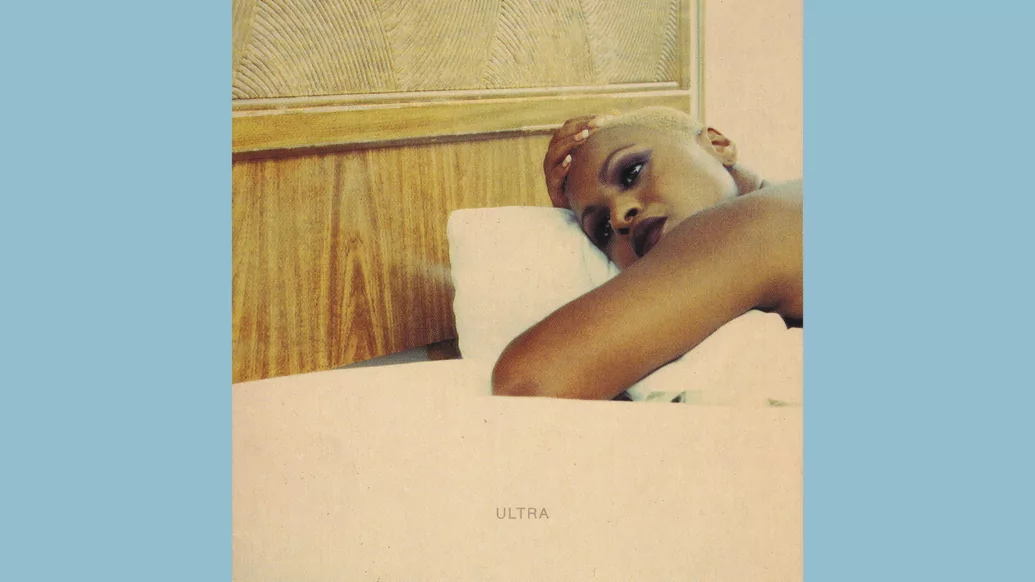

Back then, Ultra had shaved hair, dyed yellow. It was all part of the plan. “I cut it off intentionally and had it styled and coloured a specific way. I wanted everything to have a very minimalist look. I didn't want any of the message to be clouded by the flashing lights, the smoke and the mirrors. The whole design was to strip back all of the trappings that we use to cover our vulnerabilities.”

The track undoubtedly changed Ultra's life. She is still happy to play it each and every time she sings live, but has managed to have many more hits and albums in the years since. She's also grateful she had the major-label albums before the huge single success. “It gave me the foundation to be able to handle the transition that happened with ‘Free’. If everything just flipped in your universe immediately, I could see that being really bizarre, so I was very lucky in the way that happened.” Luck, of course, doesn't come into, but creative freedom surely does.