How Tidy Trax embodies the loud, proud spirit of Northern hard house

The Tidy Boys and their label Tidy Trax epitomised the early ‘00s hard house scene, at one point selling a million records a year. As they look ahead to their 25th anniversary next year, and as hard house is discovered by a different generation, they tell DJ Mag about how they coped through difficult times, how much the label means to people, and how they’re bringing through the new wave of talent

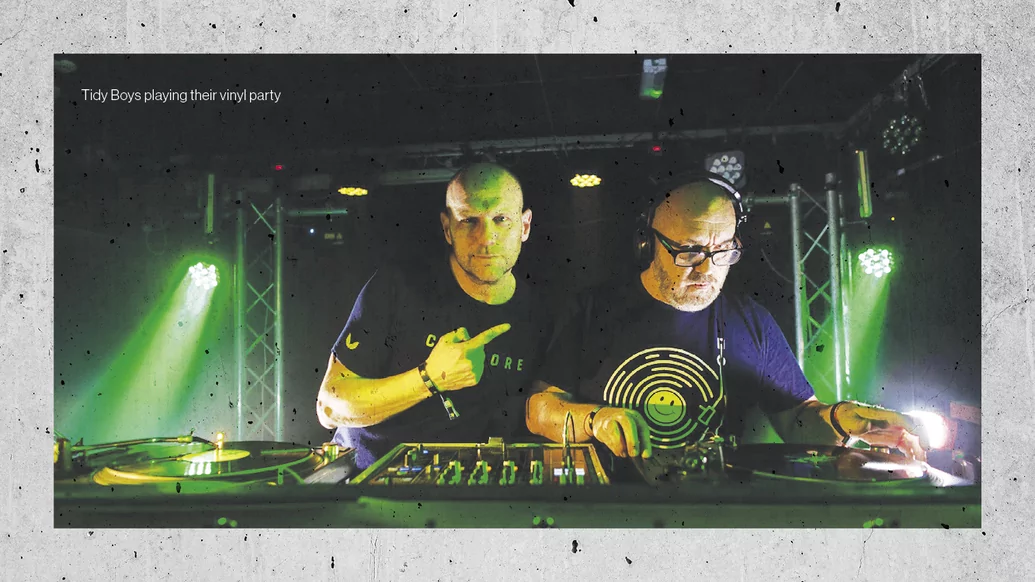

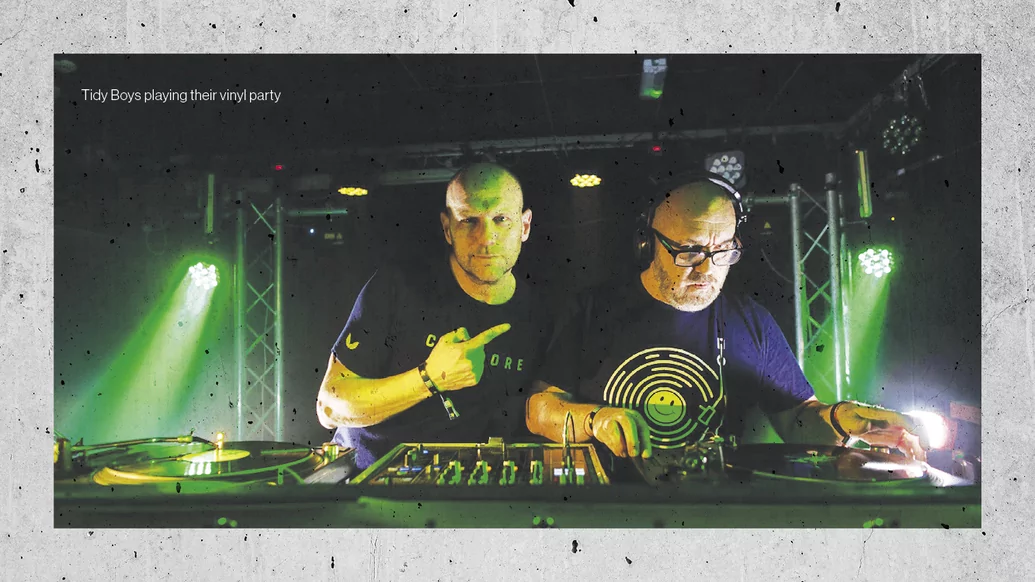

“From 1998 to 2005 we had seven years of glory, then nobody wanted to be a DJ in hard house,” admits Amadeus Mozart, one half of the Tidy Boys, when we catch up with him and Andy Pickles, the two men behind infamous Leeds-based label Tidy Trax. “Even The Beatles only lasted seven years.”

It’s a bold comparison, but then Tidy mania does mark a quarter of a century this year. This was supposed to be celebrated in July with Tidy 25: a three-day weekender in Pontins, Prestatyn, North Wales, home of their first weekender in 2002. Due to ongoing COVID-19 restrictions however, the event had to be postponed until 2022.

Putting out more than 350 records on a vast array of labels, today whittled down to a core of Tidy Trax, Tidy Two and Untidy, from its launch in 1995 the Tidy empire embodied the spirit of Northern hard house. Loud and proud, it soundtracked hugely successful clubs, such as Sundissential in Birmingham and Leeds, Storm in Coalville and Progress in Derby, and attracted thousands to the Tidy arena at Creamfields. But putting out everything from tough Todd Terry-style jackers to full-on emotional trancers, Tidy transcended its regional roots.

The label sold out events in the South, at venues such as Bournemouth’s Opera House and SE1 in London, and The Tidy Boys became international stars — once jetting into Tokyo for a single night because they were booked to play Sheffield the next. Then, after a decade on the rise, hard house went out of favour.

Despite its postponement, the initial announcement of Tidy 25 felt like a huge moment in the hard house renaissance, the genre following others such as breakbeat and jungle in being rediscovered and reassessed — old fans eager to recapture the euphoria of their golden youth, new ones digging into a hitherto unheard past.

After weathering a decade of shrinking returns though, which saw The Tidy Boys step back from DJing around 2008, then decide to only play their own events from 2015 onwards, the year they celebrated their twentieth anniversary, 2020 threw one more spanner into the works. “Like every DJ across the land, it’s been difficult,” says Andy Pickles from their office, referring to the year we lost to Covid. Tidy 25 was meant to happen last summer,and has now been postponed twice. Amadeus, aka Amo, then caught coronavirus late last year, seeming to recover before it re-emerged as long Covid a few months later, leaving him breathless and requiring a trip to hospital with a suspected heart attack.

“It’s a genuine, serious thing,” he says, breaking his usual levity. “But I’m one of the lucky ones, still here to tell the tale.”

It’s this gratitude, counting what you have and making the best of it, that marks the hard graft and can-do attitude behind Tidy’s longevity. Both now 50-something, the duo has always maintained other businesses alongside Tidy. Amo works as a graphic designer and creative director. Andy’s businesses include U-Explore, an edtech company aimed at young people, and Music Factory Entertainment, the Rotherham company that brought the duo together in the ’90s. Back then Andy worked for the business, owned by his dad, as a sound engineer and remixer for their DJ record service. Amo, who had his own studio, would send in prospective remixes, then met Andy when he started delivering them in person.

This entrepreneurial spirit has seen them — and producers from the Tidy roster – through the lean times of the last year. Before lockdown, Andy was providing music to fitness instructors to use in gyms. When restrictions hit the UK, he realised Facebook classes would mute this. So he and Amo set up Pure Energy Go, recruiting producers they knew — Paul Maddox, Rob Tissera and Paul Chambers among them — to create bespoke tracks, from nu-disco to drum & bass. “Instead of sitting home all sad, we got them in the studio so that they could pay the bills,” says Amo.

“It’s been a raging success,’ says Andy proudly. “We’ve produced 75 brand new albums for fitness and had 25,000 downloads. We carved a niche out with 3,700 instructors using our music over lockdown, which has been great.”

Rolling off these well-rehearsed stats feels at odds with two men who’ve made their reputation in a scene notorious for its excesses and live-for-the-weekend mentality. But the Tidy Boys have always seen fun as their business, and they’re serious about it. At their peak, they would tour all weekend, then arrive at their offices at 9am on Monday morning to crack on with the label.

“A lot of people don’t believe it, but we’ve never taken drugs,” says Amo, the diagnosis of a possible heart murmur meaning he didn’t even try poppers when he started DJing in gay clubs in the ’80s.

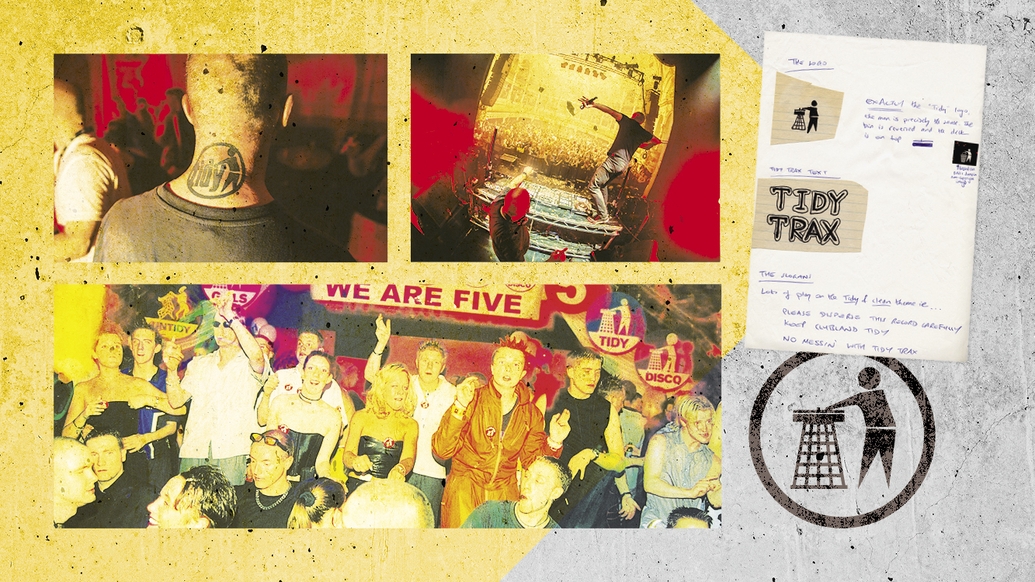

There was never a master plan, says Andy. Even their iconic logo — the no littering sign transformed into a figure DJing on an upturned bin — was just something sketched by a friend on the back of a napkin on a train down to London. But they’ve always had principles. “Have a laugh and don’t take yourselves too seriously. But whatever you do — whether it’s music, or events, or a website or a radio show — make it as good as it can possibly be.”

When it takes place next year, Amo says Tidy 25 will offer a rare opportunity for those who came to their first event, which he remembers as “a baptism of fire, very homemade”, to recapture that moment of their youth. “Pontins hasn’t changed in 50 years, let alone 20,” he chuckles. Many iconic clubs have lost their venues — Cream’s home was demolished, Turnmills where Trade was closed down, but Tidy 25 will feature “the same smell, the same dancefloor, the same euphoria”.

It will also boast, largely, the same DJs. Pulling in stars from across hardcore, hard house, trance and the tougher end of house. It’s a summation of the scene they were central to creating, an ecosystem of events that stretched from Leicester’s Storm to Insomniacz in Sheffield, and from Synergy and Goodgreef in Manchester to Promise in Newcastle. But it’s also a sign of how little those at the top have changed.

This is the impetus behind Tidy Pro, the label’s new production school. “Hard house became niche, so it became quite insular,” admits Amo. “Now we’re seeing that wheel turning again, so we have the chance to bring new talent through.” Offering mentoring and classes on components such as arrangement, composition, programming breakdowns and riffs, and mixing down, Tidy Pro aims to have the old guard help bring through a new generation.

Part of the wider renaissance, they point out, is that those who came to their first few weekenders, perhaps even meeting the person they married at a Tidy event, potentially now have teenage kids who have grown up around their music.

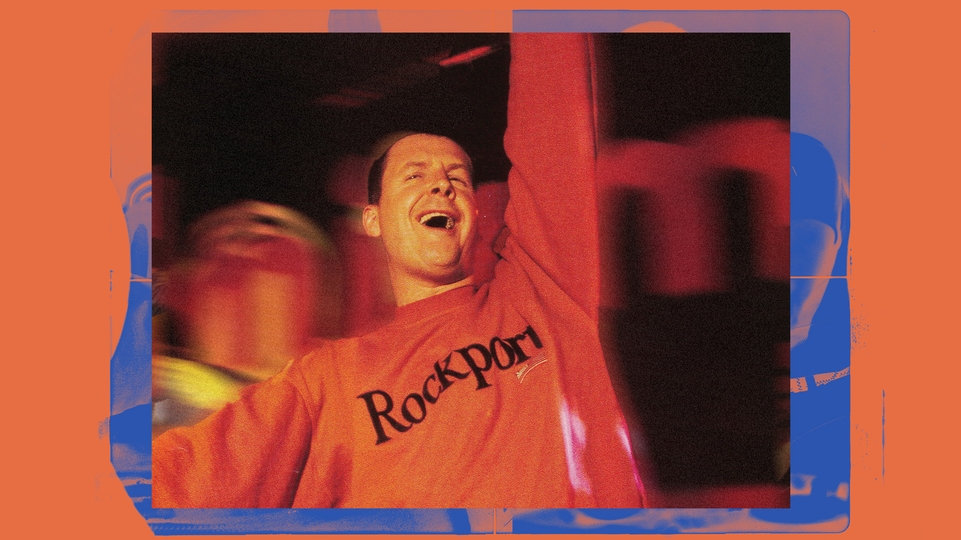

“I was influenced by my parents’ music when I was a kid and I still listen to it,” says Andy, who tells us his own 18-year-old son has absorbed a love of hard house from being around it. Hard house’s love of dressing up, from bright ’90s clubwear to full-on outré outfits, often proves mind-blowing to twenty-somethings, says Amo, “who’ve only ever been to a Defected party, where there’s one blue light and everyone is standing still. They come to a Tidy party and see people dressed as washing machines, jumping around and having the time of their life.”

The first time they saw a Tidy logo tattooed on someone’s back the size of a dinner plate, the pair began to realise the fanaticism behind hard house — and the strength of their brand. For Andy, Tidy’s weekenders have followed in the footsteps of Northern soul, the 1970s dance phenomenon that first turned UK holiday resorts into meccas for young dancers looking for hedonism. “The basis is a tribe of people coming together to celebrate their thing.”

Like Northern soul, Amo goes on, hard house is an entirely non-commercial music, barely represented on radio — so it’s built around a culture of going out and dancing. This created a close-knit community. “Hard house is the punk rock of dance music,” he says. Such is its emotional resonance, every week Tidy gets a request for the instrumental version of ‘’Til Tears Do Us Part’ by Heaven’s Cry, one of the label’s biggest releases, to play at a wedding or a funeral. “This is a culture that people have grown up with.”

If you want to run with hard house being the punk of electronic music, then Amadeus Celery Mozart, to give him his full name, is the perfect moniker for one of its main instigators. Amo was sponsored to change his name by deed poll back in 1986 while working for the charity Mind. How much did he raise? “A disappointing £250, there was a sponsored walk on the same week! But it raised awareness for Mind by getting in The Sun. Back then, nobody was talking about mental health.”

Dave Pearce, one of the few Radio 1 DJs to have repped Tidy on his Dance Anthems show, which ran until 2008, backs up this sentiment. “What I love about Tidy is its cheeky, no nonsense, two-fingers-up approach to snobby, chin-stroking, elitist clubbing. It has a real down-to- earth, working-class honesty about it.”

During his time presenting the Radio One weekend breakfast show, Pearce started sneaking hard house into the “dreary” official playlist, a tacit acknowledgment that his audience wasn’t just farmers but also “clubbers still on a mission having an after-party”. The listeners, he remembers, loved it, “the phone lines started going crazy”, but when BBC bosses found out, it was curtailed. This lack of wider recognition means that events such as the weekenders have galvanised Tidy’s barmy community.

“You can be watching Lisa Lashes on stage one minute, then bump into her in the Londis buying a pot noodle the next and ask for her autograph,” says Amo, illustrating that there are few airs and graces when it comes to hard house’s hierarchy. Pontins, by its very nature, is retro, so they’ve always run with this.

Their Prestatyn Pride event acknowledges the debt hard house, and Tidy in particular, owe to the sound’s origins in the gay scene. “For me, hard house came from Trade and the gay scene in London,” says Amo, he and Andy, both straight, regular visitors to the club where there was a network of producers, engineers and A&Rs. “Tony De Vit was the man who brought it from the gay scene, playing clubs such as Miss Moneypennys and Sundissential.”

In its earliest days, the dream for Tidy was to put out tracks that Tony would play — the pair delivering him acetates to see how they went down on the dancefloor. But as they absorbed the fluro, spiky-haired energy of local clubs such as Sundissential — which bore slogans such as ‘making Sunday holey again’, and where clubbers might turn up in an outfit made of bubble wrap and T-shirts incorporating the Special K logo — they began to create their own distinctive take. “What the North did was bring a fun element to it,” says Amo. “It was more of a party.”

“Their music was fresh and took the hard house sound up a few levels in terms of production and quality,” remembers Fergie, De Vit’s protégé, who first met Amo and Andy at one of his gigs in 1996. “Everything they did was on-point and far superior to anything else that was out there at the time, hence why Tony was a big champion of the label.”

“When Tony De Vit got offered a residency at Trade he was slotted in before me, so we had the job of bringing the place to a crescendo,” says Tall Paul, another of Trade’s DJs. “As a label, Tidy Trax was always part of those crazy last three hours taking us into Sunday afternoon.” ‘Untidy Dubs Volume One’ was one failsafe weapon for when it was lift-off.

Tony De Vit’s ‘Are You All Ready?’ started hard house’s association with the hoover, says Amo — a Juno sound that had first been popularised by Joey Beltram in the early-’90s rave days. But it was never meant to form its backbone, and may even have contributed to the sound’s demise when others began to copy it.

“Tony told me he made that as a 150bpm track he could play at the end of the night when everyone was sweating their tits off. It was almost a novelty track.”

Becoming solely associated with 150bpm — parties starting and ending at this speed — was another thing that went awry. “True hard house should progress,” says Amo, explaining at Trade it would always build to De Vit at the end of the night. “That’s what confuses people about hard house,” he says, telling us that at a Tidy event, there’ll be euphoric trance in one room, bouncy off-beat bassline in another and Patrick Topping-style grooves in yet another. “It’s everything from 128 to 158bpm and anything in-between. It’s a multi-genre genre, if that makes sense?”

“Apart from their tracks being fast and furious, nothing is off-limits genre-wise,” agrees Judge Jules, another long-time supporter, on the label’s broad and long-lasting appeal. “That’s why I love Tidy so much and why they’ve stood the test of time.”

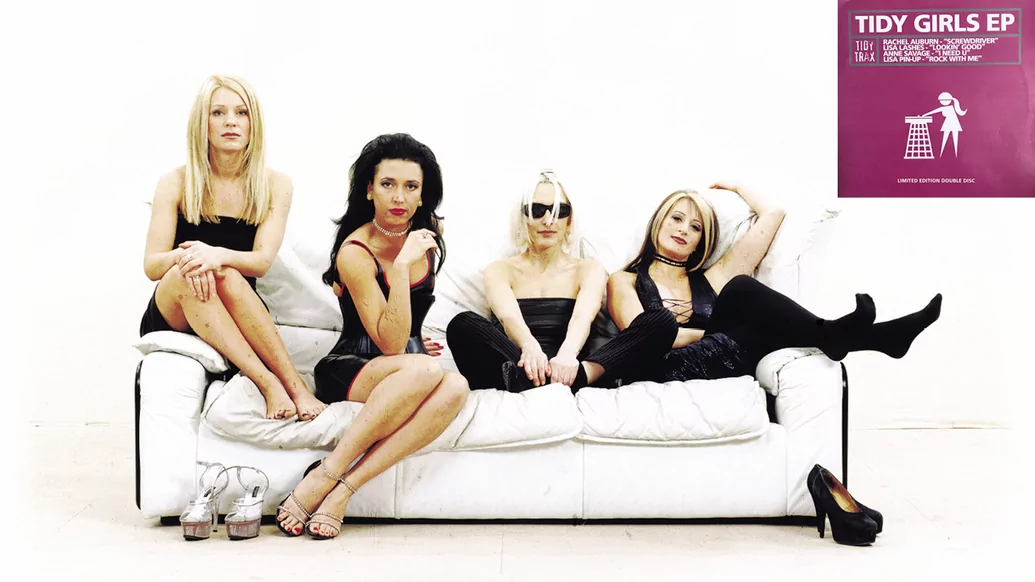

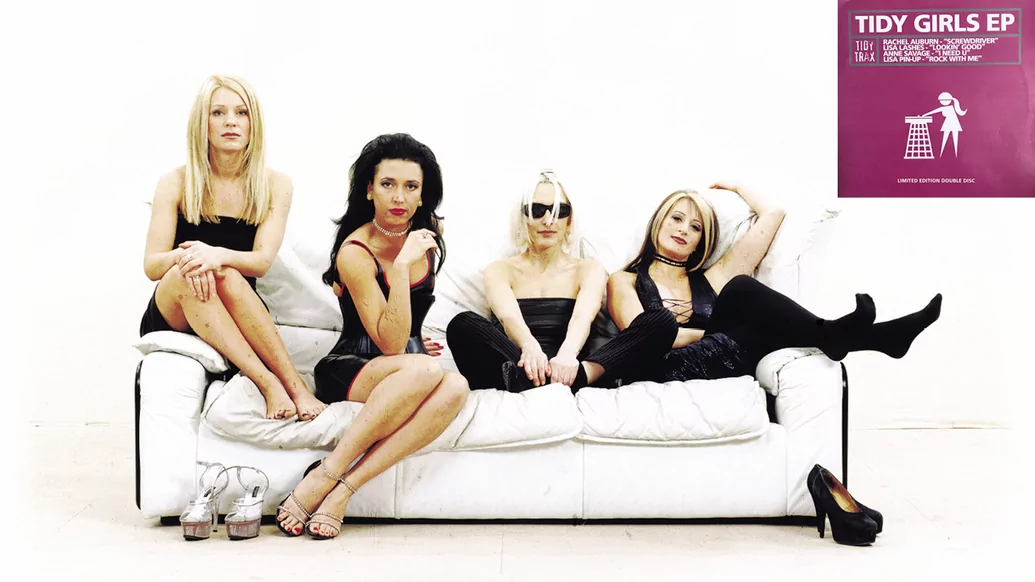

If hard house has kept evolving, then its most modern incarnations are bounce and donk, the latter a sound voyeuristically made fun of by London-centric media when it was first discovered. Amo has his own strong, personal opinion. “We made a couple of the very first bounce tracks,” he says, referencing 1999’s ‘Tidy Girls’ EP, which they wrote with Lisa Lashes and Rachel Auburn. “If you play one or two tracks a night, it’s brilliant, it’s fun, it’s fairground. But some clever dick came along and said, ‘Wouldn’t it be a great idea to create a whole scene with the same off-beat bassline?’ No, it wouldn’t.”

If this is just one example of how Tidy’s DNA has infiltrated culture, then it’s also made its presence felt via today’s new stars of house and techno. Earlier in the year Josh Butler remixed Trauma’s 1998 ‘Higher’ for Untidy, the label pushing slower, groovier sounds. His history with hard house goes way back, attending various events in his early twenties and dreaming of getting signed to Tidy.

“I’ll never forget once frisbeeing one of my demos over the barrier to Andy Pickles as they were mid-set,” Butler says. “In the North-East, where I lived at the time, hard house was just what most kids grew up listening to,” says Jackie, who became a huge Tidy fan and recently remixed Hyperlogic’s ‘U Got The Love’ for Untidy. “Tidy Trax is one of those special labels that never swayed with popular trends. I always admired that.”

“I was a huge fan of the Tidy Girls back in the day,” Sam Divine tells us, highlighting the visibility of female DJs in the scene. “As a young up-and-coming artist, Lisa Lashes and Lisa Pin-Up were a huge inspiration to me.” It’s been like coming full circle, she says, to be asked to remix Lashes’ 1999 pumper ‘Lookin’ Good’. Between 1998 to 2002, Tidy “were selling a million records a year”, says Amo, a figure that speaks of lucrative times for labels like them and their biggest hard house competitor, Nukleuz — who also appear at Tidy 25.

“The bottom really fell out of the hard house market in conjunction with vinyl in 2004 or 2005.” It led, naturally, to a scaling back of their output, but this year sees the return of a busy schedule. With Sam Divine’s remix next on Untidy, the trance-focused Tidy Two is putting out ‘Free’, a vinyl/USB release from Nicolson. And Tidy is also back on the vinyl train with ‘Resonate’ by Bryn Whiting and Adam Dixon, plenty more coming later in the year including Untidy’s 50th release, ‘Boogie Monster’ by Sam Townend.

“People ask, haven’t the Tidy Boys retired every year since 2001?” jokes Amo on the precarious times they’ve been through. “We say, always treat a Tidy Boys gig like the last time you’ll ever see them. One day it will be.” He’s old enough, he says, “to remember drum & bass being dead 15 times”. Everybody fights to be popular, he tells us, but inevitably you become unpopular. After that, it’s about waiting until you become “so cult and dated”, you’re popular again. “I’m very much about enjoying the moment,” says Andy, a level-headed attitude to success that reflects it not being his first time around.

In 1989, aged just 19, he had three UK No.1 singles as Jive Bunny & The Mastermixers, selling 10 million records. Cutting up popular rock & roll hits, despite the project’s huge commercial success, “it was slagged off for nicking other people’s music”, says Andy. The irony, he notes, was that he was knocked off the top of the charts by Black Box’s ‘Ride On Time’, a record that, unbeknown to most people, sampled Loleatta Holloway. “But one was a really cool record from Italy, and the other was a rabbit from Rotherham nicking Elvis Presley.”

It was the success of Jive Bunny that bankrolled Tidy, launching a scene and sound that has had a similarly polarising effect, rampantly successful, yet also looked down on by some. For those involved, it encompassed an entire identity, lifestyle and look. The reverberations of hard house have infiltrated mainstream house and techno, bringing with them the sparks of the relentless energy that once powered 24-hour club weekenders.

Having worked its influence largely unseen, Tidy 25 will eventually provide a cypher for the re-emergence of hard house — accompanied by a hope that it won’t just appeal to those who lived through the glory days, but can capture the attention of a new generation, too. They’re not the only ones reaching a milestone. Storm celebrates its 20th anniversary on 30th October, with Andy Whitby, The Tidy DJs and The Sharp Boys among the line-up, while Goodgreef also marks two decades on 6th November, with Eddie Halliwell, Alex Kidd and Kutski among those playing.

“I’m a strong believer in not trying to create a new sound and pander to what is popular,” says Amo on the journey they’ve been on, stepping out of the limelight for a while rather than alter their course. “We’ve always been leaders, not followers.” And they’ve got 25 years of Tidy mania to prove it.