DJ Stingray is the future-focused selector at the helm of the electro renaissance

DJ Stingray is the Detroit electro pro whose razor-sharp mixing and production chops are the result of years of accumulated skill and knowledge. Now among the most respected underground players, he’s helped spearhead a fresh appetite for electro on dancefloors, while constantly challenging himself and his audiences. DJ Mag meets him to talk history, science, futurism and where his deadly abilities behind the decks come from...

There are many ways to frame the story of Sherard Ingram’s unique rise and stature as one of techno and electro’s most consistent, authentic and trustworthy DJs. He has limitless chapters entrenched in the entire lifetime of Detroit music culture; multiple aliases and collaborative projects that place him in the Venn overlap of so many genres, from electro to downtempo, even drum & bass. He has numerous personal interests and ideologies. There are countless curious and singular details; the fact he didn’t choose the name Stingray, but was bequeathed it by one of electro’s most forthright, and sadly missed, pioneers. There’s the fact that at 52, he’s recognised more for his art now than ever. He’s still peaking and becoming even more in demand. Most importantly, he still loves what he does.

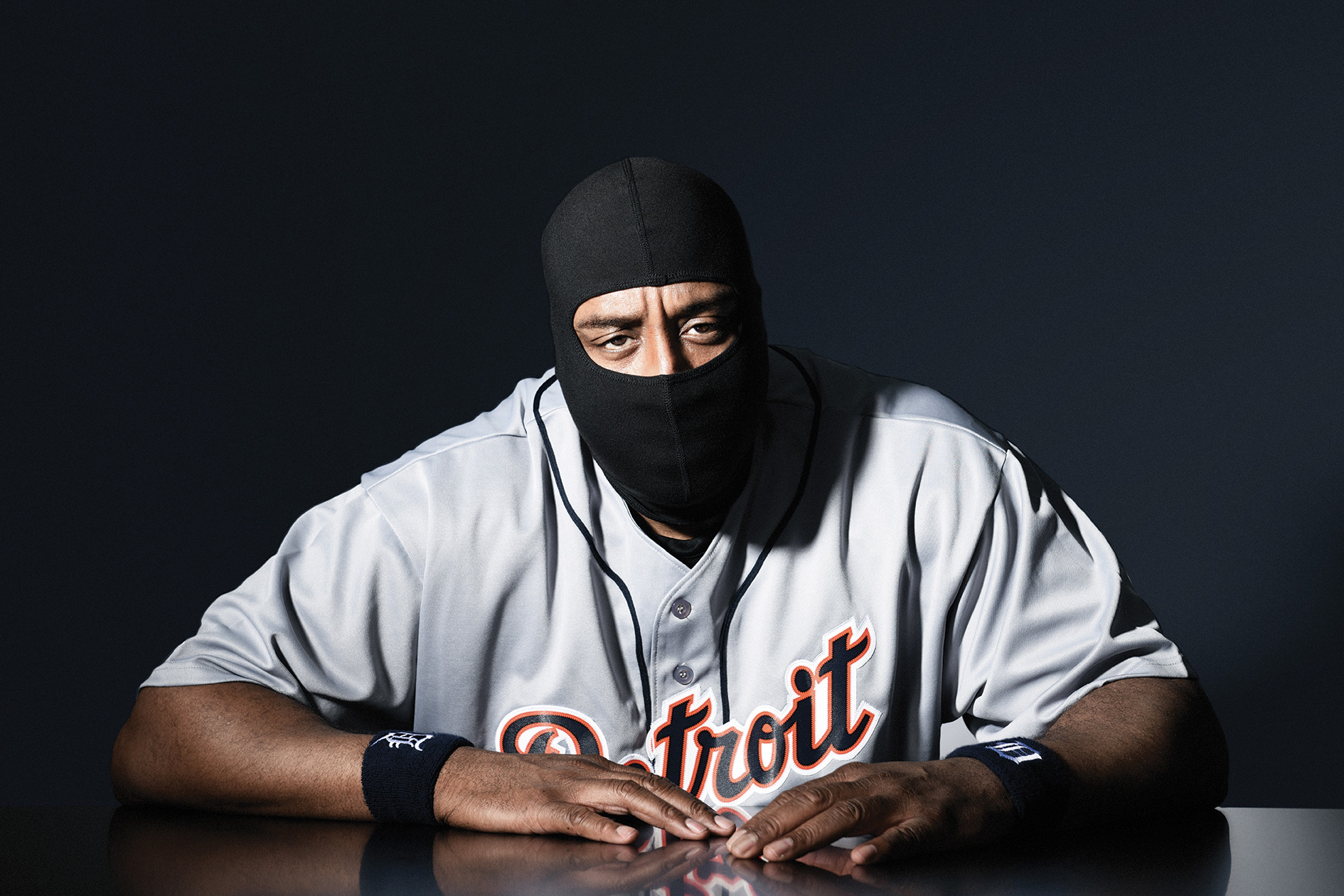

These are some of the myriad aspects of Sherard’s inimitable 30+-year career that fizz around my mind when we first meet one Sunday afternoon this summer. It’s an hour before we sit down for a lengthy interview that will touch on everything from religion to microbiology by way of futurism, hardware and his concerns about the current fascination with re-treading the paths of past techniques. We’re roaming the streets of Whitechapel looking for fittingly bleak metropolitan backdrops for a photo shoot that complements his unforgiving sonic signature. Stopping at a suitably shady car park, he begins to roll his signature SWAT mask down over his face. This writer considers how wearing a cap changes his mind-set and makes him feel as if my thoughts are kept inside his head. DJ Mag wonders if the mask has a similar effect for Sherard.

“This ain’t no comfort blanket, teddy bear type of thing, if that’s what you’re asking,” he grins, the mask now rolled over his eyes, leaving only his nose, mouth and salt-and-pepper stubble on show. “But I know where you’re coming from... when this goes on, it’s all business.”

"Did I feel like a stingray? Never. But I wasn't going to argue with James Stinson. I felt it and I understood what he wanted, because I understood the Drexciya legacy. I was Stingray from that day on."

Mask fully down, there’s an instant switch from Sherard to Stingray. He’s smiling underneath the mask, but you’d never tell. I didn’t ask him if he played poker, but he alludes to a game when we use a table as a prop in the photo shoot, and you get the canny feeling he’d clear the table with you if you did. His slightly hooded, watchful eyes give absolutely nothing away. Not his mood. Not his energy levels. And certainly not the fact that a little over six hours ago, he was tearing Fabric’s Room 2 a proverbial new one with his juggernaut blend of glacial electro, purring techno and bulbous booty bass.

313 AM

Not-so-full house: It’s 3am the night before, and Fabric is in a strange mood. Anastasia Kristensen and Saoirse are drawing deep and ploughing through fabric’s second room with rolling technoid sets, occasionally shattered by springy electro. Their selections are dynamic and forward thrusting, but the crowd don’t seem to be biting particularly hard. Little eye contact, limited cheer, a sense of languid energy. Possibly too many tourists, definitely too many lurkers looking for pickups, and just the very fact it’s the middle of summer. The UK is so loaded with events and festivals, even a premier league venue like fabric can’t pack out. Then, towards 4am, as Kristensen wraps up with a subtly ravey finale, there’s a tangible shift in the atmosphere. Tourists have left the building, lurkers luck out or fuck off, the room begins to harbour a different energy. Heads appear from nowhere through the smoke, knowing looks are beginning to be exchanged, everyone moves forward, closer to the room’s famous elevated deck pulpit. Stingray is stepping up for business. He’s about to flip the subdued, dry ice-drenched space into a ghetto ballroom and give us all a royal flushing. For the first time that night, Room 2 feels intimate. There’s a buzz, and everyone is there because they know what’s about to happen. We’re in it together, we’re ready for any destination Stingray takes us, and we’re here until 6am.

“Really? Wow. I didn’t see that,” says Sherard later when DJ Mag describes how he brought a change of mood and energy into the room. “I was in fog island! I couldn’t see a thing. Maybe that was better, though, it allowed me to focus on my DJ set. You know that was my first time at fabric, right? I wanted to bring something special.”

Mission accomplished. But you get the sense that every set Sherard plays is something special. This man is a diligent craftsman and an absolute monster on the wheels. Quick chops, flash mixes, sudden switches, and a rising sense of tension and momentum. He rips through upwards of 100 tracks across two hours on two 1210s and two CDJs. Even without the dry ice blocking his view, he doesn’t have much time to look up from the decks. But it turns out his fabric debut was special. This was a chance for him to acknowledge how London, and the UK’s heritage has inspired him, so at the zenith of his white-knuckle blend, he closed with a heavy UK bass twist and a sharp chaser of grime cuts by artists such as Rudekid. “The UK is always pushing it forward with bass and innovative sounds, and I have to respect that,” he proffers as we sit down in a bustling Turkish restaurant for the interview.

DJ Mag is interested in his thoughts on how the club has had to adopt such strict security procedures to retain its licence. Even without any knowledge of Sherard’s interests, his track title references alone suggest he’ll have an opinion: ‘Image Search’, ‘Fullbodyscan’, ‘Psyops For Dummies’, ‘Electronic Countermeasures’. To use the term ‘woke’ would be disingenuous; Sherard is acutely well read and deeply interested in science, technology, politics and the psychology and ulterior motives behind them. And he encourages friends and fans to research the topics and clue themselves up, too.

“The club’s got to find a way to maintain their security obligations but be less invasive,” he considers. “People want fun. We don’t go to the airport to have fun. Photos, fingerprints, it’s hard. I understand their challenge. It’s tough on clubbing worldwide, but fabric has been forced to take things to another level. And if you personally want to try and fight that, then you’re going to have to get politically active. The disconnected councils don’t care for culture, they don’t care for us at all, and they will stamp out what we have with gentrification.”

Lead From The Shadows

Activism is a dominant strand in the Stingray DNA. The same can be said for any of his peers making beats in Detroit during the ’80s, from one of his oldest friends Kenny ‘Moodymann’ Dixon Jr (who taught him to mix in 1983), to Belleville professor Juan Atkins (whose studio was where Sherard mixed his first single as one half of NASA in 1987), all of them fighting the commercial and exploitative framework rigidly set in place by the monolithic Motown machine.

“It was a vast commercial machine,” Sherard affirms, raising his eyebrows to full beam arch to give a sense of scale. Far from the suspicious, moody, ice-cold artist techno folklore sometimes portrays him as, Sherard seems warm, engaging, upbeat and animated. Albeit a little tired. Fabric was the latest in a long line of summer shows: 36 hours before our interview, he played his debut in Jordan; 12 hours later, he’ll be flying back to his home in Berlin, before jetting to another string of festivals three days later. There’s no sense of jadedness, or even exhaustion. There’s an energy, focus and passion.

“We were total outcasts doing something so far away from the norm that we couldn’t possibly fit in. We were constantly told, ‘You’re not even making proper music. What is this?’. Of course, now they see the impact we’ve had on the world. That’s okay, but it was painful. It was a struggle. It was a trial by fire and it kept us innovating, kept us moving and, for lack of a better term, kept us raging against the machine.”

What galvanised Sherard and his peers’ outcast status even more was how their sound wasn’t even that popular in the city. While the world looked to Detroit as a techno idyll, a haven of innovation, its protagonists were often driven by feelings of seclusion and anger. “Most of the love came from overseas and a handful of people in the city,” he admits. “Radio, club owners, promoters didn’t understand it. It was tough. Some clubs didn’t want you to throw a party, because you couldn’t make any money, not enough people were coming. The music came from isolation, frustration, wanting to see a change in the city, in the people, in the thinking.”

One infamous venue that comes up often in interviews with Sherard was fittingly called The Outcast Club. An unforgiving basement bar, home to various black motorcycle gangs, it’s here where Sherard and Dixon would play throughout the late ’80s and early ’90s. Not only did Sherard feel it was where he did make an early influence and introduce the futuristic aesthetic to people, dropping early Richie Hawtin and Ecstasy Club tracks between NWA and Public Enemy records, it’s also where he defined his signature cutlass sharp DJ style.

“How I play now is how a lot of DJs played back then,” he explains. “I inherited that style from the culture and my own experiences. That’s how we had to play. We had to keep people dancing, so if we wanted to change minds, we had to tease and sneak things in. And that felt like a universal force. I don’t care what side of the city you were from, we all agreed as DJs that we wanted to change the course of the music.”

The Strategy Of Tension

Sherard considers the parallels between the political climate of that seminal period of creative incubation that did indeed change the course of music, and now. Heavy-handed policing, severe lack of support for those on, or under, the poverty line, Reagan’s Star Wars and Trump’s Space Force; the similarities are strong. The two starkest differences now, he observes, are apathy and an innate distrust of both right and left sides of the political system among black voters and Trump’s “unabashed naked capitalism and control”.

“America voted Obama two straight terms. That was no coincidence,” he considers. “But during that time, the right wing media worked their hardest to stir up hate and populist sentiment. Trump came in at the right time. He saw what other politicians couldn’t see. For years you’ve had guys like Rush Limbaugh whipping up rhetoric, and people were ready to install order when there was no disorder. America is a very controlled society, whether people want to see it or not.”

For perspective, Sherard doesn’t think we’re living the most Draconian period in recent American history. That chapter was actually under a Democrat government with Clinton and his Three Strikes bill. “He made the drug war even more acute and intense,” sighs Sherard. “But the political climate is always tense.”

It was to this tense backdrop that Sherard wrote his first influential, breakthrough records as the main producer behind Urban Tribe (a fluid collective of which Sherard was the only mainstay, Urban Tribe comprised sporadic members such as Carl Craig, Kenny Dixon Jr and Anthony Shakir). Early releases such as ‘Covert Action’ first emerged in 1990, but Urban Tribe truly dented the hazy sub-consciousness of trip-hop in the mid ’90s when they signed to James Lavelle’s cult beat stable Mo’ Wax, complementing the label’s influential smoky signature with inner city sleaze, grit and hip-hop. As with almost every record Sherard has ever been involved in, the title of their debut album ‘The Collapse Of Modern Culture’ came from a dark and wary place.

“During that time I was reading a lot of, and became open to, COINTELPRO,” he explains. “A hugely invasive programme used to supress any type of activism. I was reading about that, and also reading various revelation prophecies like Nostradamus, and I saw the sky falling. I was young, I was relatively naïve. The sky was falling. Plus I was raised as a Christian, you always look at the sky for the return of the redeemer, so there was always this state of alert. Between political reading and indoctrination, the title came from a culmination of things.”

Later Urban Tribe records, released during the mid-2000s on Aphex Twin’s Rephlex, were even more explicit in their references. ‘Authorized Clinical Trials’ and ‘Acceptable Side Effects’ left you under no illusion as to the dangers Sherard was warning you of. By now, the sky had well-and-truly fallen. The albums marked a new chapter for Urban Tribe, and added to his consistent theme of awareness, reading and effectively knowing your enemy. Sonically these records reflected this, too. The tempo, tension and textures of these albums were raised to the wily, roughened highs more associated with his signature as Stingray. Because by then, that’s who he’d become...

Hydro Doorway

One of the most intriguing chapters of Sherard’s story is how he actually became DJ Stingray. This story’s been told many times but is impossible to overlook — Sherard’s life changed immeasurably when he was invited to join one of the most mystifying, folklore fuelled and vastly influential collectives in Detroit techno history, Drexciya. The moment the anonymous collective’s gravely secretive ringleader James Stinson gave him his trademark Underground Resistance mask (it was a woolly one which Sherard quickly replaced for his SWAT mask), and named him Drexciyan DJ Stingray, Sherard, by now in his mid thirties, entered a whole new paradigm.

It’s a neatly ironic tableau; Sherard had the rare luxury of not having to pick his own DJ name himself and instead was precision christened by one of techno’s most famously anonymous, nameless (yet multi aliased) men, who debunked any spotlight or attention and only became truly identifiable after his passing in 2002. “Did I feel like a stingray? Never,” Sherard smiles. “But I wasn’t going to argue with that man. I felt it and I understood what he wanted, because I understood the Drexciya legacy. We’d had conversations about his philosophy, so I thought, ‘Okay, I’m Stingray’. I was Stingray from that day on.”

The Drexciya philosophy is based on an Afro-futurist narrative concept around the perpetual movement of a voyage, and an underwater Drexciyan race who’ve descended from pregnant slave women, thrown overboard during their own voyage of deportation. The name Stingray added to their consistent aquatic tropes, but also acutely embodied his slippery, killer attitude behind the decks. With the full Drexciyan affiliation, Sherard was propelled from a largely studio-based career in the ’90s to a global stage in the 2000s, as Stinson and partner Gerald Donald came out of the shadows a little and took Drexciya into a new narrative as a trio. Sherard tells of a folder of plans and designs a freshly inspired Stinson gave him during this time, which he’s never shown in public. Sadly, these plans never came to fruition, as Stinson passed away of a heart defect aged just 32. “I took the Drexciya off my name out of respect,” explains Sherard. “I never wanted people to think, ‘Who is this clown riding off the back of Drexciya’s legacy?’ I wanted to show eternal respect and gratitude. He got me onto the world stage and I probably wouldn’t never have made it as a DJ to this stage otherwise. It wasn’t something I was after.”

Weaponised

From here, Stingray’s ascent has continued over the last 15 years. Gradually, unhurriedly, never pushed. Sherard has admitted in the past that travelling and ‘breaking’ Europe was never part of his plans. He was far more focused on releasing records he believed in. But each year his prominence on international, and especially European, line-ups has grown, to the point where he’s been a Berlin resident since 2016 (“closer to where my music is appreciated, and closer to people whose music I appreciate”). Each year has also seen him sharpen and redefine his bruised drum assault more and more. Following his last Stingray-esque Urban Tribe albums, a gentle slew of releases and collaborations has persisted.

The brittle beats, dystopian atmosphere and sudden snaps of aggression of his ‘Aqua Team’ releases; his reconnection with Drexciya’s Gerald Donald (aka Heinrich Mueller, aka a founder member of Dopplereffekt), both on the ‘Drexciyan Connection’ EP and later as NRSB-11; and his mistrustful messages such as ‘Disinformation Campaign’ and ‘Who’s Watching The Watchers?’ as Stingray 313, an alias that inspired dBridge, who would incorporate Sherard’s beats into his Autonomic mixes and invite him over to play at Exit Records events.

Another interesting UK collaboration that highlights Stingray’s versatility and the universal appeal of electro was ‘Stingray Enters The Unknown’ on DJ Haus’s Unknown To The Unknown in 2011. Or, much more recently, on cult London vinyl-only label Behind This Wall, with his savage and systematic breakdown of Joors’ ‘The Nine’. These are just a handful of examples of Sherard’s consistently crisp, defiant electro designs. There are many more (including his first-ever official DJ mix album last year for Tresor, ‘Kern Vol 4’). Each one documents Sherard’s implicit insistence in forging new paths, ideas and textures within the electro context.

“We don’t need records that sound like they were made 30 years ago,” he states succinctly. He becomes even more engaged when asked about techno’s current retreat back to using classic analogue hardware. He considers it revivalism, not futurism. “We only worked with limitations because we had to,” he continues. “We didn’t romanticise about them. If you had a four-track board and you could get an eight-track, you’d get it. People romanticise about limitations, but I don’t care what you say, as an artist your only limitations are in your head. You choose how expansive you want to be.”

This is where Stingray’s personal philosophy perhaps differs from that of Stinson and Donald — while Drexciya was rooted in a narrative and mythology, Sherard speaks strictly as a realist and scientist. “Electro has lost that connection with science and technology and futurism,” he explains. “Maybe because things have progressed, so quickly people feel disconnected. It’s more work to be a nerd, it’s more work to be techy. You have to have some proficiency mentally. You can’t just be a consumer end person. I think maybe we have gotten a little lazy. We’ve lost our vision. This music started around futurism. And if we lose that we become pop music. Bad pop music.”

Science Realism

Sherard cites sound design on movies and video games, and experimental artists as such as Silvia Kastel and Russell Haswell, as examples of exciting futurist blueprints right now. In terms of his own future futurisms, we’re just a little too far away in time to reveal what he has in store for early 2019, but be assured it’s in-keeping with the activist ethos that’s run through his entire story. And indeed life; beyond music, Sherard is just as driven by the pursuit of progression, problem solving and, ultimately, the truth.

“Scientific realism is the impetus for futurism,” explains Sherard, whose dominant scientific interests are in microbiology, pathogens, genetics and evolution. “As humans we have to look for solutions and, for me, science is a practical solution to all our problems. Pollution, antibiotic resistance, traffic; there are solutions waiting for everything in methodological talk and thought. We make tools. They’ve evolved from the hammers to machines, but now we make tools on a microscopic level. We find solutions.”

For a man who’s dealt almost exclusively in dystopian sonics that are rich in political reference points, has invested time studying systematic government control, dark intelligence operations and is mostly recognisable wearing a SWAT mask, Sherard is a lot more positive than you might assume or looks might suggest. He defines himself more as a pragmatist than a pessimist, and explains how pessimism is a result of people thinking they need to solve problems on their own. “We need to work together,” he reasons. “That’s why we thrive as a species. There’s no one single individual or culture or sector to solve things. We all have to work together.

“So no, I’m probably nowhere near as pessimistic as people may think,” he continues. “Am I dystopic? Yes. But I prepare for that through my art and keeping abreast through science. That’s why I post about scientific developments and talk about these things to people, to give people some type of hope.”

Meanwhile back at fabric, now 5am, Sherard has instilled us with another sense of hope... hope that his final hour goes on forever. With Marcel Dettmann blazing big guns in the main room, Stingray is playing strictly to a loyal, locked-in crowd who embrace every barbed break and bleak emotional blast. He might not be able to see us or feel our energy through the fog, but the rolling four-to-the-floor tracks are becoming more infrequent as he gets dirtier, darker and more twisted. “I gotta make people comfortable first. Then when they’re used to me, and I think they’re ready, that’s when things get dropped on them,” he grins.

There are many ways to frame Sherard Ingram’s unique story so far. But only one way to conclude it; when this man says business, he means it. With or without his SWAT mask on. Here’s to the future. Here’s to futurism.