Adam Beyer: Techno's uncompromising kingpin

Adam Beyer is one of the biggest names in techno, renowned as much for his DJ sets as his highly successful Drumcode record label. Ahead of another hectic summer schedule, we meet him at his home in Ibiza to find out how a childhood tragedy gave him the drive to succeed in music, how he’s striving to make his events more environmentally friendly, and how an uncompromising attitude has helped launch Drumcode’s artists onto the world's biggest stages...

Pics: DANIELLA MIDENGE

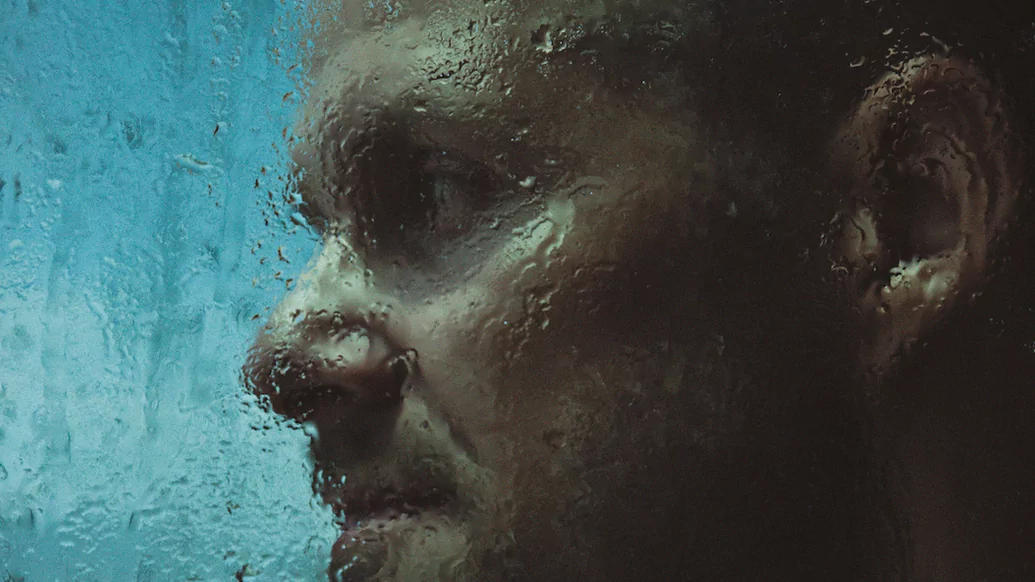

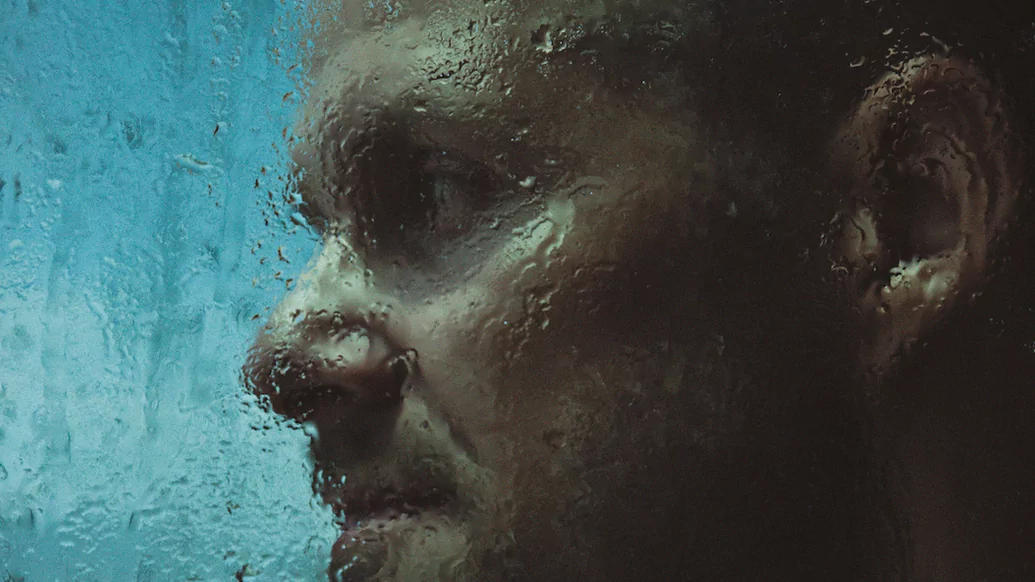

“I was quite angry as a teenager,” Adam Beyer says. We’re sitting across from the Swedish DJ in his Ibiza home, talking about the death of his father, who passed away when Beyer was 13 years old. “I never really dealt with it properly. I thought I had. That’s something that’s been coming up over the last few years, which I started to realise. Maybe I wasn’t angry, I was cynical, and felt a bit betrayed in life,” he says. “You know, when you lose someone that early, a parent, it can make you feel a bit...” he pauses, looking away. “It does something to you.”

It was a dark time in Beyer’s life. Growing up in Stockholm, he wound up with the wrong crowd after his father died. “There was quite a lot of shit going on,” he says. “We were out a lot in the streets, and there was stealing and fighting.”

His father had been an amateur drummer, and Beyer himself played for three years, from age nine to 12, before he found DJing. Influenced by videotapes of DMC performances and a local DJ who played on Sweden’s Radio P3, Beyer started learning to beat juggle, scratch and mix with hip-hop records. “You know, the whole routine,” he says. He was enthralled. “It’s never been any question since then. I told my mom, ‘I’m going to be a DJ’.”

While today that’s a fairly normal teenage aspiration, in the late ’80s things were different. But Beyer’s mother saw music as a positive influence in Adam’s life, and used a portion of the small inheritance he received from his father’s life insurance to buy him turntables. Beyer thinks it saved him. “Some of my friends from back then are dead today,” he says. “It definitely saved me from doing a lot of stupid shit, and not finding my place in life. I was pretty good in school up until I was 12 or 13, but then I just didn’t care so much. Also because I got obsessed with music.”

Adam’s obsession eventually became a career, propelling him to heights of global fame and success in techno. He was able to channel the anger of his youth into a strong and serious identity built around the genre he remains deeply loyal to today. Politically radical records by Underground Resistance became intensely personal to him. After discovering Jeff Mills at Berlin’s Hard Wax during a trip to Love Parade in 1993, Beyer understood he could combine his DMC skills with techno — playing hard and fast on three decks with quick cuts and mixes — and his genre purism further hardened. Mills’ style also brought out the bombast in Beyer’s spirit, which remains a key component of his music. “I was always a Jeff guy,” he says. “Some people were more Robert Hood, but I always liked it bigger.”

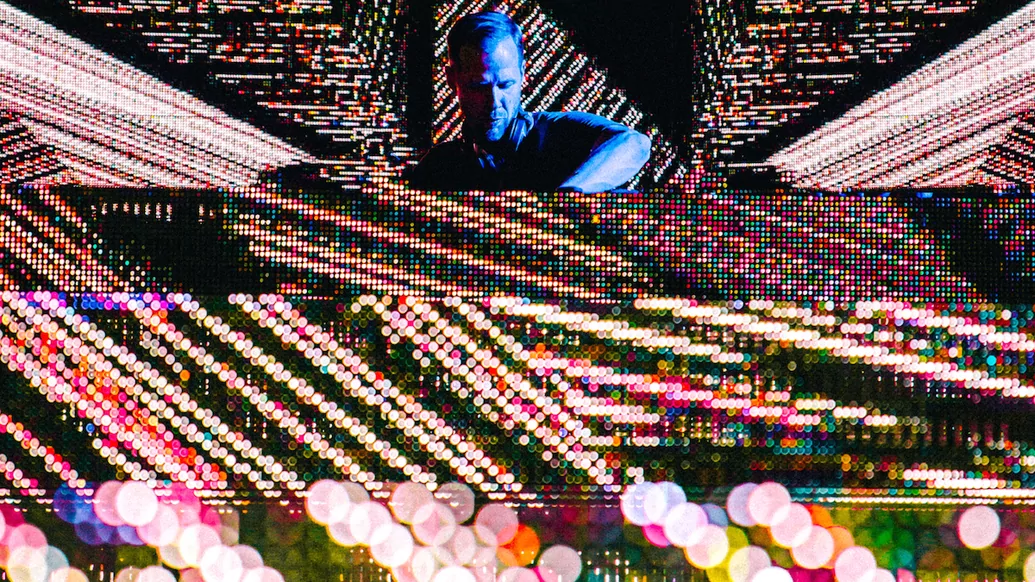

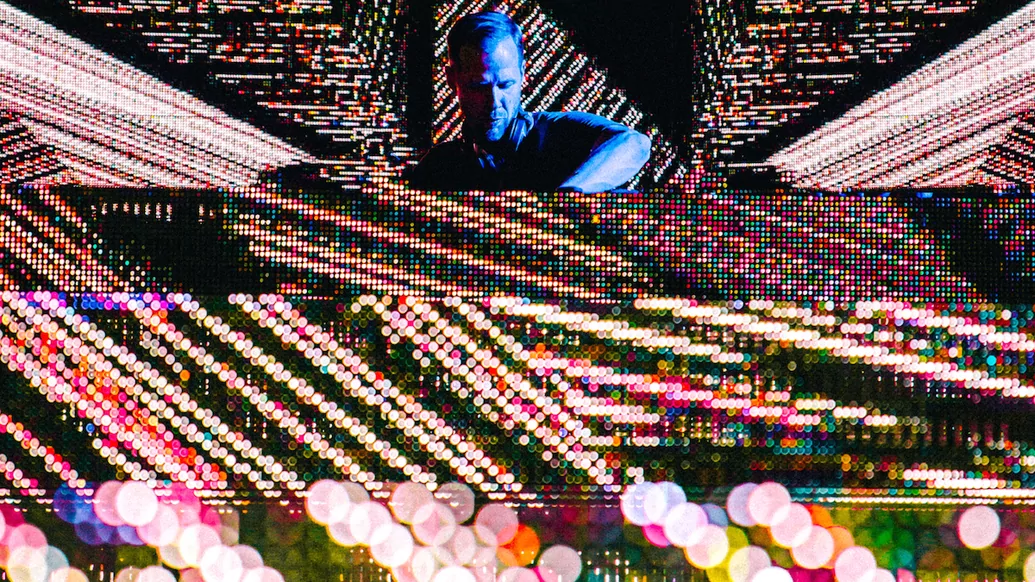

BIG TIME

Beyer’s life today is typified by big. His label, Drumcode, is probably the most widely recognised techno imprint in the world. He regularly plays the largest stages at the most immense festivals, including his own Drumcode events. His radio show, which soon turns 10 years old, reaches 22 million people per week across 85 stations worldwide. As we talk, a large psychedelic portrait of a lion hangs behind him. And his bulky but very friendly Rottweiler — named Kate — nuzzles close, keen for more affection.

Kate is one of several animals that inhabit the sizeable Beyer property, including horses and several cats (one owned, many feral). Adam’s wife and partner of many years, Ida Engberg, is the keeper of most of these creatures. Years ago, she took a big step back from her career as a DJ to help take care of the couple’s three young children, the youngest of whom adorably interrupts our conversation midway through to ask for a snack, before her mother calls her away. It’s a quaint moment in an otherwise incredibly busy life for Beyer.

This hectic-ness is partly why he now lives in Ibiza full time. His large white house sits high in the rolling hills of Santa Gertrudis, surrounded in nearly every direction by dusty green pines. He doesn’t meditate like many of his peers, instead finding spiritual solace in daily workouts and regular hikes around his house. While his partying days have slowed with family life, he says he’s still feeling the effects of a late night at the Zoo Project opening a few days earlier, where Engberg played. He’s open and honest, and seems completely at ease, even down to earth; happy to talk about anything.

Though much of Beyer’s current fame can be traced back to launching his label in 1996, his first release came on Adam X and Jimmy Crash’s Direct Drive when he was 18 years old. He’d left school to work at a record store called Planet Rhythm with Cari Lekebusch and Glenn Wilson. They became part of a crew of Swedish techno artists, which also included Jesper Dahlbäck and Joel Mull, who were helping one another and pushing the new Swedish techno sound to listeners around the world. “I think it was easy to get recognised as a sound because it was like four or five producers, with more and more labels and things going on,” Beyer says. “So the world was like, ‘Wow, there’s something new coming from Sweden’.”

Beyer’s star was rising, but after five or six years, his heart wasn’t in it anymore. “I got a bit fed up with the whole hard techno thing, because it just went harder and harder,” he says. He started seeing “skinheads” at his gigs, and the mood was shifting to something aggressive. He also started playing Ibiza, and in the early 2000s found himself living in a villa with Ricardo Villalobos and Richie Hawtin for several summers during the minimal boom. “For three years I got invited to come here and do the whole ceremony or whatever you’d call it, starting with Cocoon on a Monday and ending on a Thursday,” he says with a laugh. “It was wild.”

Beyer was in the middle of a musical sea change, one that he deeply identified with. “It just made sense, and reminded me of the early ’90s recordings — the fun in the music that I was missing. It grabbed me.” He began releasing on labels such as Plus 8, Soma and Nova Mute, partly emulating the minimal and Balearic sounds he was surrounded by, while adding his own hard-edged twist. He also put Drumcode on hold, unsure if he’d ever re-launch the label.

By 2007, however, minimal was winding down, and things with the label were back in full swing. Releases came from Dustin Zahn, Joey Beltram and Steve Lawler, followed in 2009 by Alan Fitzpatrick and Joseph Capriati’s first releases on the imprint. “I would say looking back at it, when we went back to techno, it was slowed down, that’s where it really started to take off. And we had the first big records again — like really big records — around 2010,” Beyer says. That year, Fitzpatrick released his ‘Paranoize’ EP, Capriati dropped ‘Gashouder,’ and Ben Sims put out ‘Hypnosis/Psychosis’. All three typified what would become known as the Drumcode sound: big, booming basslines, slow and funk-driven techno rhythms and dramatic melodies and breakdowns. Perfect main stage material, in other words.

“I feel what I’ve been trying to create with Drumcode was to keep it very positive. I felt sometimes techno could be — especially where I came from — elitist. I left that behind, because I felt there was a lot of negativity. We see it in certain parts of the community where there is a schoolyard mentality going on”

A POSITIVE THING

That same year, Beyer launched Drumcode Radio, which transformed how fans came to interact with the label. Suddenly, Beyer’s booming Swedish baritone voice and the Drumcode sound were reaching into headphones, living rooms, people’s gyms and workspaces, while sound-tracking some of the most special moments in their lives. Drumcode became like a “lifestyle brand,” Beyer says, and the fans responded intensely, with Drumcode tattoos, handmade flags (before Drumcode sold them), and even requests for Beyer to witness their wedding proposals.

“I didn’t expect it,” Beyer says, but the reaction, which he describes as “beautiful”, fits perfectly with the ethos he has tried to build around Drumcode as a culture. “I’m happy, because I feel what I’ve been trying to create with Drumcode was to keep it very positive,” he says. “I felt sometimes techno could be — especially where I came from — elitist. I left that behind, because I felt there was a lot of negativity. We see it in certain parts of the community where there is a schoolyard mentality going on. And for me, that is not representing the music. So at some point in my career, I just said, ‘Okay, I’m done with this, I’m gonna make this a positive thing’.”

But with success comes criticism, and Beyer isn’t immune. “It does get to you when you get shit from right and left all the time, because you’re not doing this or you’re not doing that,” he says. “And after a while, it can break you or it can make you stronger.” Beyer reckons he’s better at letting criticism go these days, but dealing with accusations that he’s only in it for the money seem particularly unfair to him. “If I was in it for the money, I would have done trance in the ’90s and EDM in the 2000s,” he says. Sure, he’s built a massive brand and pushed himself to achieve what many other people haven’t, or wouldn’t. “But if it wasn’t for passion, and for ultimately the music and always putting that first, I wouldn’t be able to succeed in doing what I did,” he adds.

HALLOWEEN

A cornerstone of his success is the annual Drumcode Halloween events in London, which have been running since 2011. Beyer has been playing in the UK since the ’90s. His first London gig was at a club called Cloud Nine in ’95 or ’96, but his connections to the UK run deep. His long-time manager lives there, the Drumcode office is in London, and until vinyl crashed, all the label’s wax was distributed out of London. “I also have relatives in England,” he says. “It’s always been a part of my life. I started going there early.”

Beyer’s unsure why his sound has connected so well in the UK, but he puts it at least partially down to some of the label’s earliest influences. “We had a lot of UK-influenced undertones in the music,” Beyer says. “In the ’90s we were using the Reese bassline, hoovers and jungle sounds in our techno,” he says. “We had a couple of key releases early on with those kinds of sounds. I don’t know if that has anything to do with it.”

Beyer has been a long time drum & bass fan, citing Source Direct and Metalheadz, and still collects the genre today, but his success in England is also connected to how often he has played there. He was a regular at Fabric early on, and played legendary Leeds venue The Orbit in its heyday — though entrenching himself in the early UK techno scene wasn’t part of some grand strategy. “That was the beauty of the ’90s — no one had a strategy. We were just young and wanting to listen to the music and get off our heads,” he says with a wry smile. And by 2010, when London Warehouse Events approached him for a label showcase, he said yes.

The story of how the Drumcode Halloween party — which started at the 1,000-capacity Ewer St, before moving to the much larger Tobacco Dock — became one of the capital’s biggest techno events is humorously un-dramatic. After their first one-off event, they decided to throw the next one on Halloween. “And we said, ‘Okay, let’s do another one next year’. And they started to get quite popular...” Beyer trails off, laughing.

His partnership with London Warehouse Events has now made him the face of Junction 2 festival, which just hosted its fourth edition at Boston Manor Park under the M4 motorway. The festival’s runaway success has been impressive, though not necessarily unexpected. The line-ups cater to diehard electronic music fans and more casual consumers alike. And this year, sets came from Discwoman affiliates Volvox and Umfang, Fabric cohorts Craig Richards and Ricardo Villalobos, Ibiza giants Maceo Plex and Tale Of Us, and of course Adam Beyer, who once again presided over his Drumcode stage at The Bridge, hosting Richie Hawtin, Joseph Capriati, Ida Engberg and Bart Skils.

Beyer insists Junction 2 is about more than impressive line-ups and eye-popping locations. “For many years I played a lot of English festivals, and you would see these amazing flyers, but then you got there and it’s always a bit disappointing,” Beyer says. “In London, it’s like, ‘The production’s shit, they don’t look after us as well as in Europe, the soundsystem’s not as good’. So I was like, ‘If we do this, we have to up the game’. We have to show how a festival can be done, because I’ve been playing so many in Europe, and especially in Holland, where it’s like 10 times better for everything, and it must be possible to do in England as well. So we wanted to up the game 300%, which I think we managed to do. And that’s why it’s quite successful now.”

ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT

As the marketable face of Junction 2, as well as one of its directors and shareholders, Beyer also wanted to make sure the festival’s environmental impact was as small as it could be, with vegan food options and a low carbon footprint. His wife, Ida, has been the main driver in his growing consciousness about the environment. She’s vegan, and while Adam isn’t, he does try to limit how much meat he consumes, and for the most part keeps red meat out of his diet.

“When you live with someone who’s talking about it on a daily basis, you get informed,” Beyer says. “I also read a lot of news and I like to keep myself informed. And then we have the Swedish girl who’s now up for the Nobel Prize, Greta [Thunberg] — what she’s doing is incredible. I mean, it’s not a joke. It’s our future, our planet’s future and our kids’ future, so I think everyone has to be involved.”

Like Junction 2, Adam’s own Drumcode Festival, which debuted in Amsterdam last year, is almost completely sustainable. “It’s impossible to not leave any footprint at all, but to our best abilities, we’re trying to make it environmentally friendly,” he says. Expanding to two days this year, August’s event will once again feature stars from the label, including Charlotte de Witte, Enrico Sangiuliano, Amelie Lens and Alan Fitzpatrick. Despite the difficulties often associated with throwing a festival — many often lose money in the first few years — Adam says it has been a “huge success”, and he is “counting on it to grow and become a mainstay in the Dutch festival scene”.

Aside from the events he’s involved with, festivals have inevitably become a major part of Beyer’s itinerary. He still plays clubs, of course, and recognises their importance as breeding grounds for tomorrow’s artists and trends. But with so many DJs of all stripes vying for the bigger stages and pay-cheques festivals provide, he does understand why people are worried about the impact festivals are having on club culture.

“Of course clubs are suffering,” he says. “It’s impossible to offer the same experience as a festival — the same fees, the same anything. So I think we’ve seen the number of clubs decreasing all over the world and in Europe especially over the last years, partly because of the kids so used to being spoiled with big productions and big line-ups and whatnot.” Fans can hardly be blamed for wanting what festivals provide, and Beyer isn’t blaming them. Instead, he puts much of the responsibility on newer artists and their managers, who seem to have disregarded the old unwritten rules about how fees are supposed to operate.

“They get a certain fee, like a standard festival fee, and then will ask the same for club shows, which is insane,” he says. “And then if [clubs] don’t pay that, they say, ‘Okay, we’re gonna go and do that festival instead’.” Beyer lowers his fee when he plays smaller venues, saying, “I get paid a lot less for certain club shows, because I know the capacity and that’s how we work. We don’t charge the same fee to everyone. We would adjust accordingly to the venue and to the circumstances."

ROAD TEST

It’s another example of someone who’s been striving incredibly hard to do things the right way for nearly 30 years. As Drumcode’s principal A&R, Beyer is famously uncompromising with the music his label releases. Artists often joke that Drumcode’s D.C. initials stand for “don’t compromise”. He tries to road-test nearly every release, and wouldn’t sign anything he wouldn’t play. “And when I’ve done it, I’ve usually regretted it,” he says. When an artist sends a release that isn’t quite ready, he often sends them back to the studio. “I’m not satisfied until it’s perfect,” Beyer says. “Sometimes things slip through over the years, because you can’t always be perfect, but I think the level of perfection has been maybe higher than in some other places.”

Brazil’s Wehbba — whose reputation as a highly proficient producer preceded his work on Drumcode — once remarked that his music “had reached a whole new level” since working with Beyer, and that “the care and effort put into every single release is second to none”. Beyer’s willingness to work with his artists is at least partially why the imprint has become known as a career maker, having helped launch artists like Joseph Capriati, Alan Fitzpatrick and Enrico Sangiuliano into the stratosphere. “Anyone now signed to Drumcode that gets to play the shows are almost guaranteed to have a career,” Beyer says. “That’s why people are so crazy to get on the train.”

This responsibility does not weigh lightly on Beyer’s shoulders. As the label has grown in size, the process for selecting new artists has become incredibly challenging. “You don’t really want to sit and be in charge of people’s careers,” he says. Signing one artist inevitably means another equally skilled artist won’t join the family. And with so many good demos coming Beyer’s way, he’s had to find other reasons to bring someone into the fold.

“If they’re really dedicated and really want it, and they understand the family that we have now, it makes a big difference,” he says. “I mean, I’m very diplomatic, and I work quite well with difficult personalities, because, you know, artists are artists, everyone’s not the same. But I have maybe three or four artists that are similar, and you have to pick one. So then you’re obviously gonna pick the one that you get along with more, or is the better DJ, or has a personality that I think would work in the scene. Which sounds cruel, because it’s almost like pop now. You start looking at other things than only the music.”

Potential cruelties aside, it’s a method that works, and watching new Drumcode artists rise up the ranks is incredibly rewarding for Beyer. “It’s amazing,” he says. “I think the reason it’s happening over and over with me is because I’ve always been happy when people succeed.” Adam remains sharply conscious that his label attracts people who, “want to be in the middle of the biggest shows”. Inevitably, DJs like Capriati and Fitzpatrick will grow beyond Beyer’s shadow and want to do their own thing. They might even surpass Beyer in stature, though that doesn’t bother him. “While I’ve had experiences over the years where I’ve been pushed down by others,” he says, “like big DJs that always want to maintain control and keep that gap in fame to them, I keep hearing from people that I’m not like that, and that’s something I’m proud of.”

“While I’ve had experiences over the years where I’ve been pushed down by others, like big DJs that always want to maintain control and keep that gap in fame to them, I keep hearing from people that I’m not like that, and that’s something I’m proud of"

Right now, what seems more daunting than anything to Beyer is charting a course for the future of the Drumcode sound. As genres continue to merge, and older trends return to fashion, it gets more difficult to intuit what the future of techno might hold. “I used to feel always it was quite simple — I just knew,” he says. “At the present moment, it’s all acid trance from the mid-’90s, which to me is quite crazy.” Beyer released a few similar sounding records when the style was first in vogue, and understands the cyclical nature of electronic music. But that hasn’t made looking toward the horizon any easier.

“There’s not one clear trend anymore,” he says. “There are several trends, and you can kind of do whatever you like.” With so many styles and so many artists all vying for their chance to be on the label, Beyer seems overwhelmed at how much good new music is out there. “I never follow trends, and I was always trying to see what’s next — to hear a record that really inspires you,” he says. “That is not maybe the case in the same way, because there’s so many big tracks; there’s like 20 new big tracks all the time. In the past there was like, one. It’s so much of everything.” He’s also not entirely certain what the Drumcode audience wants. It’s grown so large, and has several points of entry beyond club nights, so pinpointing the typical fan and their music tastes seems almost futile.

Challenges aside, Beyer sits in a supremely enviable position, which he’s worked extremely hard to achieve for himself. With two festivals, a major label, a successful roster of artists, a massive DJ career, and a loving family, Beyer could easily rest on his achievements. But he is not the type to slow down — at least not yet. “I think I have maybe 10 more years in me, doing this at this level,” he says. “But you never know. I’ve heard other DJs say that, and that was 20 years ago, and they’re still playing.” Which begs the obvious question: what’s next?

In his immediate future, the Ibiza season looms large. He’s playing once at Paradise, several times at Privilege for Resistance — including for a Drumcode takeover — once at Elrow, and twice at Cocoon. Sven Väth’s party has returned to its original home of Amnesia this year, a club where Adam says he’s “had some of my biggest moments as a raver and DJ”.

There’s a possibility Beyer might be throwing more Drumcode festivals, but nothing is yet concrete. More pressingly, Drumcode Radio might soon be coming to an end. "I’m reaching 10 years at the end of this year, so we’ll see if I continue with the radio. Maybe 10 years is a good point to call it a day and start something new.” With the rise of online streaming, he thinks fans are coming to expect a lot more in terms of how music reaches them. “So we’ll see,” he says.

He’s also building a studio in his house, and says making music again, which he’s hardly had time to do in the last 10 years, is something he’s deeply anticipating. “That’s one of the most fulfilling things, to just create without an exact purpose,” he says. The studio will also fulfil another goal: turning the Beyer house into a creative hub for the Drumcode family. “Hanging around the pool, barbecues... make it a living place for creativity, and being involved in a lot of production. That’s my dream.”

SELF-AWARENESS

But more than anything else, Beyer says he’s working on himself. Along with his realisations about the anger he’s carried with him since his father’s death, he now sees the need to achieve a healthier work-life balance. “I’ve been close to burning out a few times,” he says. “All the mental health stuff you read about, I’ve had those issues as well. I think pretty much everyone with that kind of schedule for too many years would reach a point where they feel like it’s quite punishing.”

He feels closer than ever to achieving that balance since moving to Ibiza. “I think I’ve become more spiritual since I moved here,” he says. “Ibiza is a very spiritual place. There’s a lot of plant medicine going on, which, in the past, I wasn’t that interested in. But this place has opened up a whole new avenue to happiness and self-awareness. And it has nothing to do with more money or more big festivals.”

With newfound self-awareness comes a desire to break through self-imposed limits as an artist. “The anger I was talking about as a teenager, maybe I’ve been bringing that with me throughout my career, and that has made me not one hundred per cent able to come out of my shell as a performer. That’s something I want to get rid of. And I think moving here, and going through what I’ve been through here, is part of me finding the final piece of myself to fully become the artist I want to be.”