What is the future of sampling?

Sampling has been a central pillar of music production in the 30-odd years since MPCs hit the shelves, crucial to the development of hip-hop, breakbeat, house, jungle, and countless splinter styles across the dance spectrum. In the decades since, ever-shifting technology has slowly vaporised the analogue world that sampling was built from. Here, Chal Ravens asks: how is the culture of sampling evolving?

The sounds of this summer were an infinity mirror of summers past, from the charts to the rave: the freak funk of Rick James, the plastic twang of ATB, the inescapable plundering of Aqua. After hearing the fourth or fifth interpolation of ‘Barbie Girl’ at an otherwise cool and underground rave weekender last month, I couldn’t help but wonder: have we hit peak sampling?

I’m not the only one who’s noticed. Wading into the discourse recently, Skee Mask lamented the number of DJs playing “bullshit” edits of “whatever songs they heard on the radio when they were still shitting their pants”. Even artists who might normally defend the humble pop bootleg have had their fill, with VTSS struggling to excuse a hard techno flip of Gotye’s ‘Somebody That I Used To Know’. Is this a cultural crisis? Or could our moment of extreme salvagecore be the first tremors before something more seismic?

Sampling has been a central pillar of music production in the 30-odd years since MPCs hit the shelves, crucial to the development of hip-hop, breakbeat, house, jungle, and countless splinter styles across the dance spectrum. From the extreme margins to the Top 10, it’s now so ubiquitous as to be almost invisible. Perhaps that’s why our summer of cheeky edits feels like an aberration: too bait, too easy, like being interrupted by three-chord punk in the middle of a Steely Dan marathon. (Granted, simplicity can be refreshing.)

But the culture has never been static. Digital technology has accelerated a once-arduous process, arguments over copying and attribution have been racialised and reformulated, and actual records have disappeared into the ether. Perhaps it’s not a coincidence, then, that all this retromaniac recycling is popping off at the exact moment that we’re confronting the future-shock of artificial intelligence, as datasets reduce copyrighted works to mulch and large language models reveal music we never knew existed. And, in an increasingly virtual world, songs are shattering into pieces, reduced to fodder for infinite remixes.

It’s hard to talk about without sounding like you’ve drunk the techno-utopian Kool-Aid, but the culture is shifting. (It’s not funny — underground music scenes only do this when they’re extremely distressed.) So what next? The analogue world that gave us turntables and MPCs has been slowly vaporised; sampling will have to evolve too.

Early evidence of this shift can be detected in dance music’s ongoing pop glow-up, as I explored in DJ Mag last year. Cheeky edits are taking up more space than ever in festival sets, perfectly primed for sharing on socials. Sometimes it’s as simple as making the right joke at the right time, like the Aqua samples floating around all Barbie summer, a cultural moment that’s generated its fair share of silly-season bootlegs as well as the occasional belter. But samplemania is just as intense in the actual charts, cluttered with regurgitations of hits by Tom Tom Club, Rick James, Grandmaster Flash, and so many more, while well-known samples from the ’00s and ’10s are a large part of the fuel for New York drill — the most reported-on rap scene right now.

If it’s not already clear, we’re focusing on sampling at the macro level — using a few seconds of a song, or interpolating a lyric or melody, as part of a new composition. We’re not considering the kind of “one-shot” drum hits and other micro-samples used by producers to build beats and textures.

One reason we’re seeing historic levels of interpolation in the mainstream is the emergence of the “song management” company. As Jayson Greene explained for Pitchfork, a new breed of asset managers is betting on the longevity of individual songs rather than the marketability of artists, with companies like Hipgnosis spending millions on the catalogues of James Brown and Prince with the intention of extracting fresh value from their songs — for example, flipping Rick Astley’s IP into a hit for rap joker Yung Gravy. “The Hot 100 right now feels as recursive, all-encompassing, and allergic to new input as the Marvel Cinematic Universe,” Greene laments. “But just as with the MCU, once you tune out the parade of surface nostalgia, it’s easy to hear the massive engines of corporate consolidation whirring beneath”.

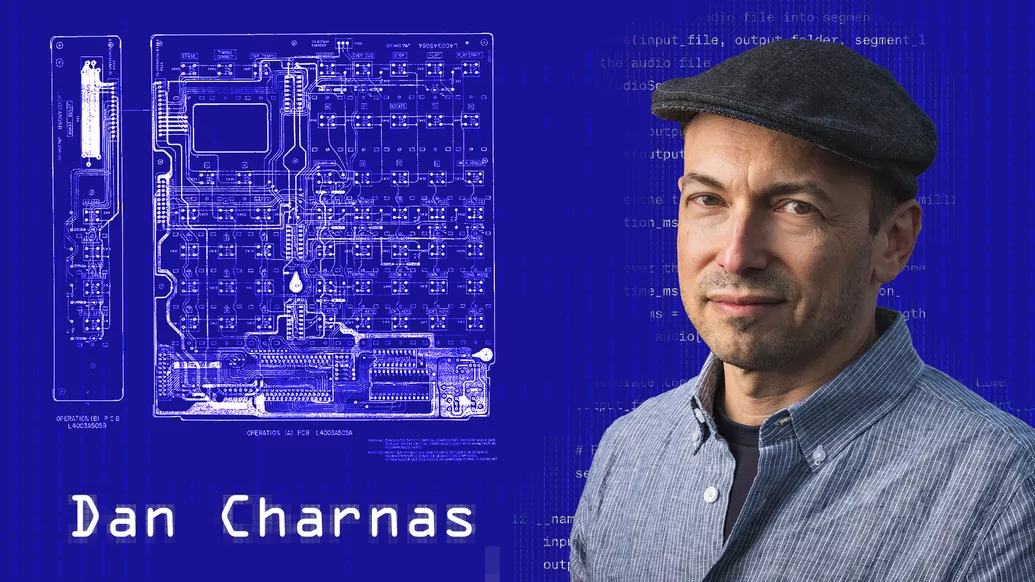

“The idea that you could create an entire way of making music by quoting those things is a very New York, very post-Great Migration way of thinking about what music is and what it's supposed to do” – Dan Charnas

In the EDM corner, workout playlists are stacked with swole updates of Ciara, Fatboy Slim and other millennial hits. These ‘wallybangers’, as industry folk have dubbed them, offer a light bulb of recognition in a reassuringly familiar format. The same tactic worked for Peggy Gou on crossover tune ‘(It Goes Like) Nanana’, which lifts the famous plasticky guitar preset from ATB’s ‘Til I Come’ for an instant jolt of familiarity. Yet none of this explains why the Sugababes and Deadmau5 keep intruding into alternative dance zones — it can’t be for business reasons. Electronic music used to be a neophile’s dream. Now it seems the urge to build an oppositional subculture has given up on the promise of futuristic technology, instead seeking out escapist re-readings (and queerings) of the past.

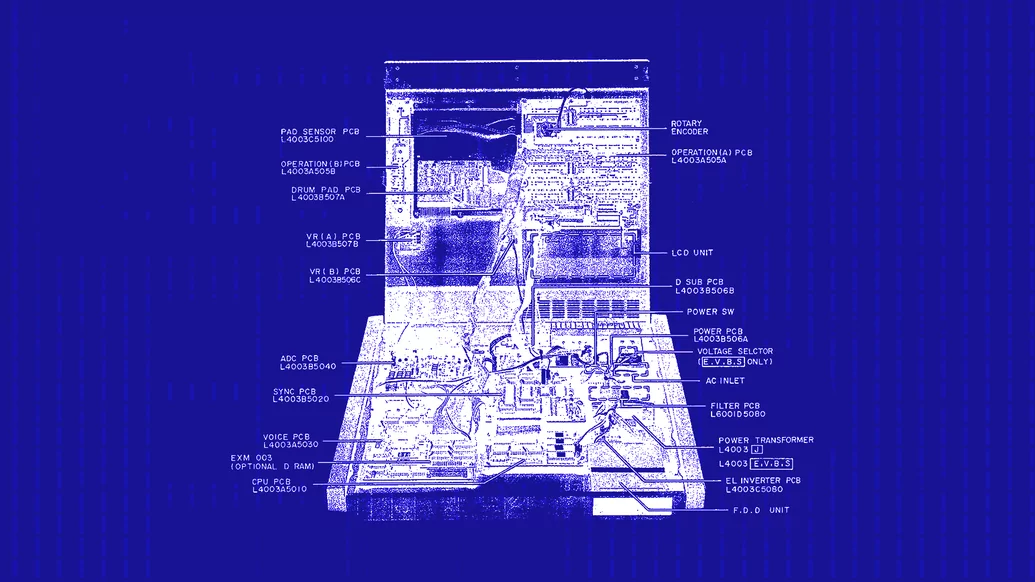

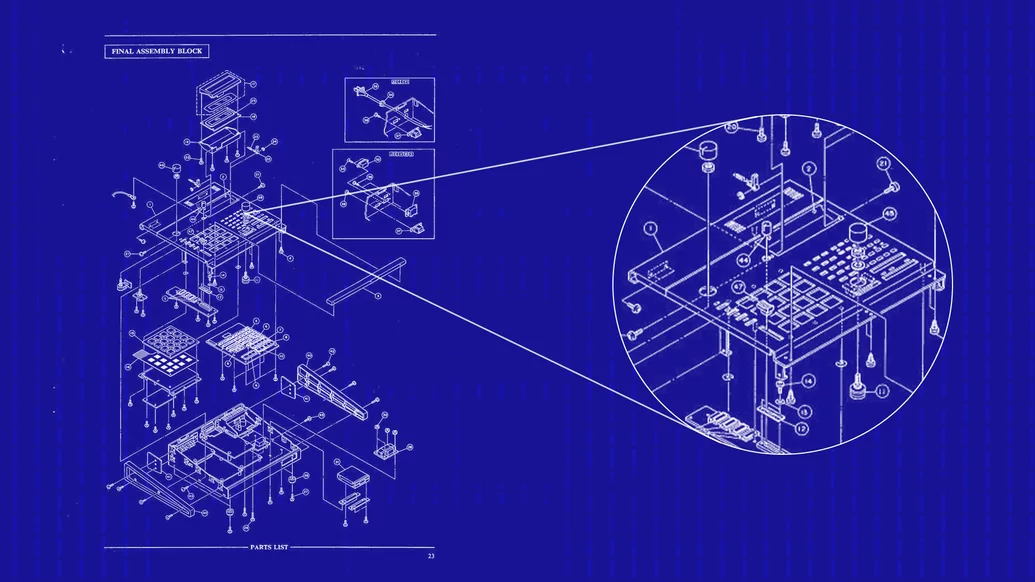

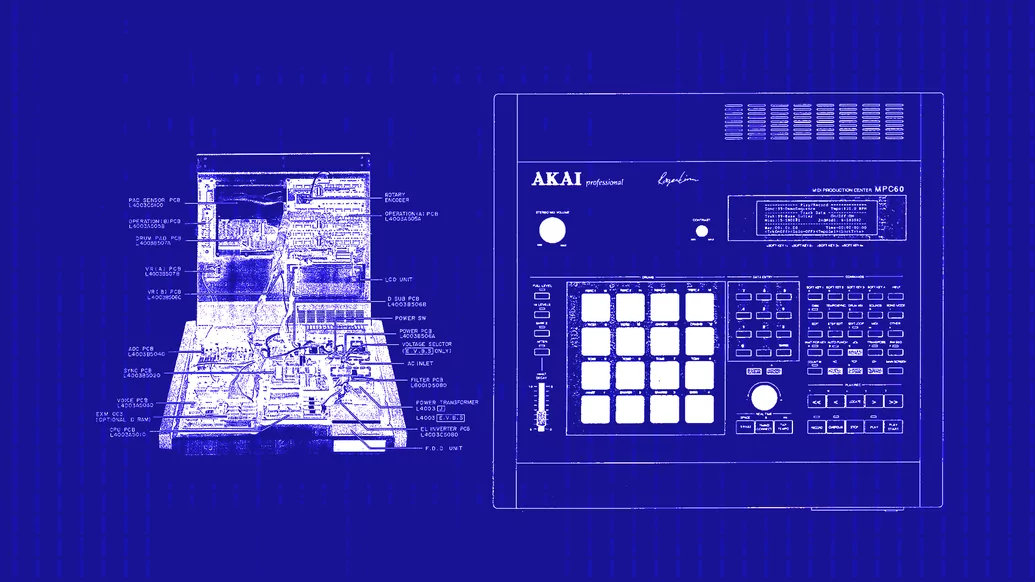

Sampling, in the sense of quotation, is a basic fuel of culture. In the 20th century, with the arrival of photography, film and recorded music, the practice of sampling inspired artistic movements that took media as both its subject and its source material, from literary modernism to Pop Art. In music, that exploded in the 1980s with hip-hop and the impact of the arrival of the MPC, designed for Akai by Roger Linn (maker of the Linndrum, Prince’s favourite drum machine). His MPC60 was the first of a series of workstations that were compact, sturdy and completely intuitive. The pre-loaded stock sounds weren’t bad, but it was obviously more interesting to load it with your own samples, taken from any record, tape or broadcast you could access.

The results included a string of maximalist hip-hop masterpieces in the late ’80s, including Beastie Boys’ ‘Paul’s Boutique’, De La Soul’s ‘3 Feet High & Rising’, and Public Enemy’s ‘It Takes A Nation of Millions To Hold Us Back’. These records were technically creative and laden with intertextual meaning, building a new language from fragments of existing culture: made by “media hijackers”, in the words of Chuck D.

That era has since been thickly conceptualised, with sampling described variously as a form of collage, an archival activity, a way of accessing memory, or the quintessential postmodern artform. Writers like Tricia Rose and Greg Tate defined it specifically as a Black artform, one that made connections between disconnected generations by “collapsing all eras of Black music onto a chip” — as Tate envisaged in the film The Last Angel of History. Sampling also troubled dominant ideas about authorship, showing that the meaning of a work isn’t decided by its creator but constantly reinterpreted by its audience — a much-discussed notion in the ’80s and ’90s following deconstructionist philosophers like Roland Barthes, who famously announced the “death of the author”.

Dan Charnas, author of Dilla Time, a book about Detroit hip-hop legend J Dilla, believes that the emergence of sample culture was closely connected to a demographic shift in America. Hip-hop was invented by the children of the Great Migration, the movement of millions of African-Americans from the Southern states to the industrial centres of the north in the middle of the 20th century. “After world war two, millions of Black folks headed north to join folks who were there prior, fleeing Jim Crow,” Charnas explains from his base in New York. “Those folks brought their music with them — first jazz, then rhythm & blues and soul.”

What developed for the children and grandchildren of these migrating workers was “a kind of library culture for history”, with kids in Harlem and the Bronx using records “as a way to revel in this shared language”. Emerging producers like Q-Tip started digging Roy Ayers and Lonnie Liston Smith out of their parents’ collections, a historicising process that turned hip-hop into a kind of “ancestor worship”, as Tate once wrote. “The idea that you could create an entire way of making music by quoting those things is a very New York, very post-Great Migration way of thinking about what music is and what it's supposed to do,” argues Charnas.

In 1991, two notorious legal cases over uncleared samples marked the end of hip-hop’s media hijacking era. However, as law professor Thomas W. Joo points out in a journal article, no crackdown was going to stop sampling from becoming a dominant method of production, in hip-hop and beyond. As with the attempts to ban home taping and file-sharing, producers found their own way around the rules.

Most continued to use samples, either by licensing them, disguising them, or simply releasing their record and hoping for the best, as many still do. Even in the supposedly lawless ’80s, the Beastie Boys spent at least $200,000 on clearance fees for ‘Paul’s Boutique’. In contrast, when De La Soul decided to take their chances on a few uncleared samples, they ended up getting sued for millions by ’60s rock band The Turtles. There’s an important principle at play, as Joo emphasises: it’s only illegal if you get caught.

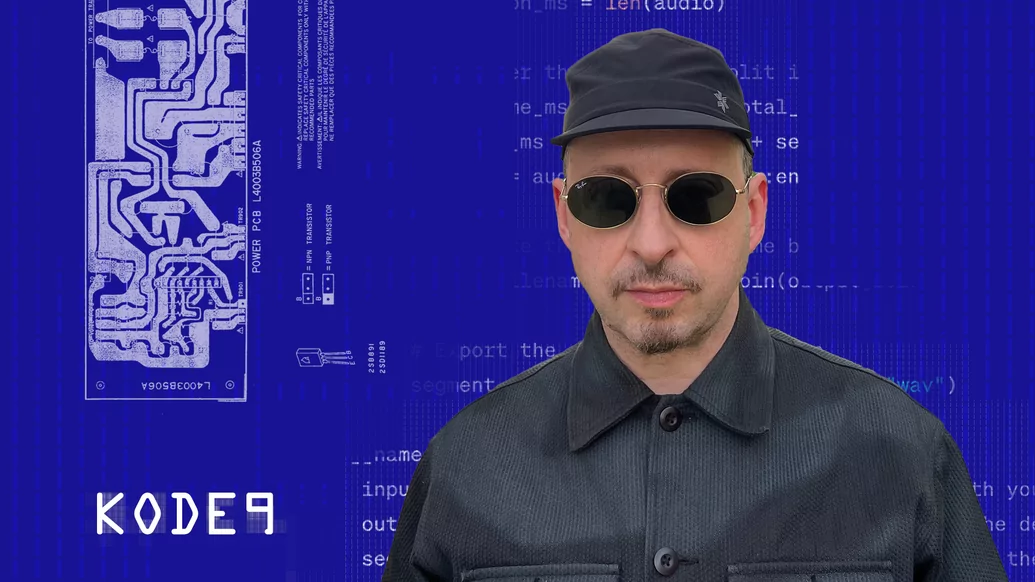

In the digital era, producers began to bypass the fiddly business of sourcing and extracting samples by turning to sample packs, which save time, cost little to nothing, and remove potential legal headaches. The criticism is that ready-made samples make the world sound more homogenous, corralling producers into familiar grooves which appropriate the historic innovation of others. Theorist and DJ Steve Goodman, AKA Kode9, unpacked this quandary in an essay for e-flux, pointing to the ways in which music software “encodes” centuries of knowledge and technique, flattening rich cultures into algorithms. The history of western popular music is “a story of the automation of the Black Atlantic”, he suggests — using Paul Gilroy’s term for a multinational Black cultural identity — “from standardising sample packs to the uploading of abstract rhythmic processes.”

It’s a train of thought that leads us to rethink how producers and listeners in the global north interact with dance movements from the global south. The spread of broadband and cheap computers made it possible for a genre like gqom to travel from Durban to London, but also enabled London producers to download a sample pack and slap together a gqom track for practically nothing. Goodman has no time for “It’s A Small World”-esque, global village utopianism. Beneath the “veneer of democratisation”, he writes, the usual systems of exploitation are at work.

Sampling emerged from an analogue culture, one built from physical hardware and shaped by the mushrooming of mass media — a world vastly different to the one we live in now. In the decades since, we’ve ascended to the clouds of digital audio workstations, online archives and unlimited streaming, our daily interactions increasingly virtual and algorithmically determined. That’s enough of a transformation to suggest that sampling, as a process and a culture, is about to evolve. And while it’s a mistake to point to technology as the sole driving force of culture, when it comes to electronic music, the thrill of technophilia has always been part of the deal.

By now, the song has all but detached itself from the physical world, absorbed into a vast, immaterial blob of music which almost nobody pays for, except in exchange for their data. A deluge of AI-powered music technology is beginning to disrupt our already shaky ideas about authorship. Even the idea that a song should be a finished statement is fading, according to music critic Kieran Press-Reynolds. In an essay for the No Bells blog, he points to a spate of “otherweirdly mashups” and pitched-up remixes going viral on TikTok: this year’s big hit is a daring combination of Timbaland’s ‘Give It To Me’ and a scat-singing man in a toilet, a horrorshow believed to be Generation Alpha’s first meme. Record labels are cottoning on too, commissioning their own sped-up or slowed-down versions of tracks in an attempt to seed a viral hit. The effect is disorienting: who knows, or even cares, whether a song is the original or a remix, fanmade or official?

“You get a record and you’re like: that drum break is dope but I wish I could get rid of some of that music that’s filtered behind it. Now you can do it. It’s just insane to me” – DJ Khalil

Press-Reynolds suggests that the popularity of speed remixes and fanmade bootlegs “reflects a generation who grew up with abundant customisation options”, from Bitmoji to Nike ID. It’s not hard to imagine an album release going the same way: what if artists just shared their stems and invited anyone to participate in versioning? Big pop albums already interact with dance music in this way unofficially: Beyoncé’s ‘Renaissance’ was stripped for parts and flipped into club edits within days of release.

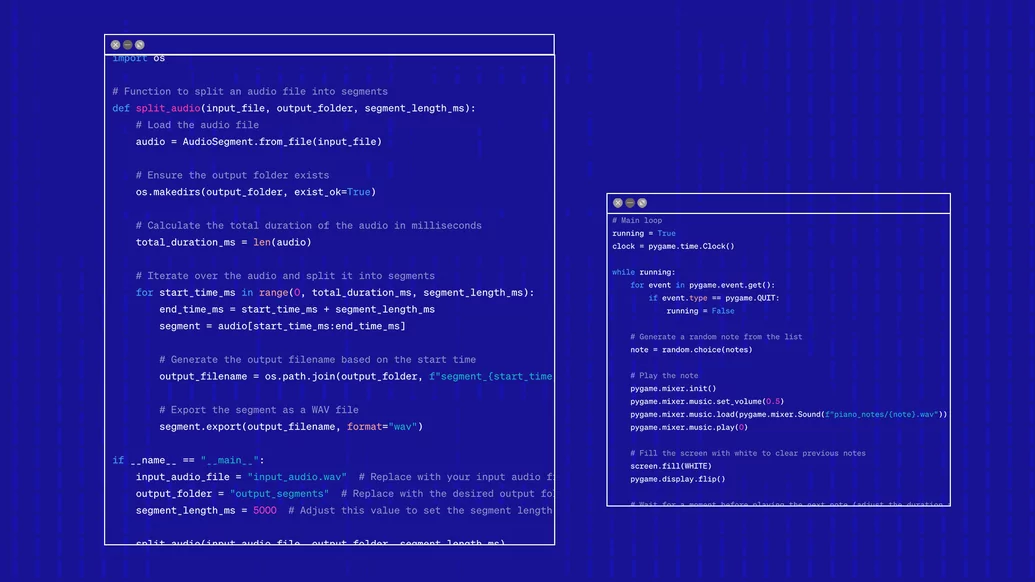

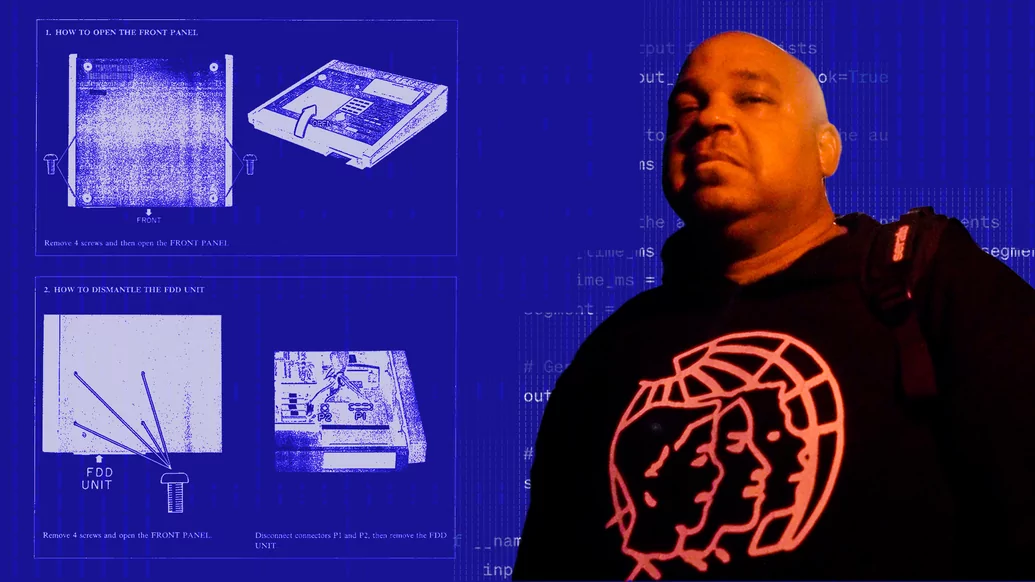

Radical change is afoot for veteran musicians too, like DJ Khalil, a West Coast producer whose vintage-leaning productions have served 50 Cent, Joey Bada$$ and Anderson.Paak. His music would be unimaginable without the samples he digs from dollar bins and YouTube, which makes him an unlikely ambassador for a new tool that threatens to render those skills obsolete: Serato’s AI-powered STEMS, which gives producers and DJs the ability to separate drums, vocals and bass at the touch of a button. Maybe that doesn’t sound like much. It didn’t to me, until I watched Khalil pull out the drums from a vintage soul record to create a clean loop in seconds. Until now, producers have either had to sample isolated elements of a track, like the drum breakdowns that were the foundation of hip-hop, or develop a deep understanding of how to manipulate EQ to extract a usable sound.

Speaking from his studio in LA, Khalil seems genuinely impressed. “It’s kind of what we’ve always wanted to do in terms of sampling. You get a record and you’re like: that drum break is dope but I wish I could get rid of some of that music that’s filtered behind it. Now you can do it. It’s just insane to me.”

For producers, STEMS makes a typical studio task much faster and easier. For DJs, though, the same tool might bring new levels of complexity and spontaneity to a performance, allowing artists to leap into the unknown. (Stem separation technology is also available in VirtualDJ and several other brands.) Similarly, when Pioneer developed the sync button, they didn’t just install a cheat code for n00bs — they also freed up DJs to attempt ever more complex blends, as mastered by multi-deck exponents like Ziúr, as I wrote about in 2019.

Stem separation technology is almost too effective for sample-hunters like Khalil. “There’s so many options, it’s crazy. It’s almost too much,” he notes. Interestingly, the subtle imperfections in the sound quality of AI-generated stems are what appeal to him the most. “What makes it dope is that it’s not 100% clean. That’s what makes it more hip-hop, in my opinion. If I was making a pop record I couldn’t use it the same way because the clarity is not as good. There’s still artefacts.”

Other AI tools pose different problems for producers. Google Assistant is now capable of identifying samples of less than a second, as one sample-hunting Discord community discovered this year. In one night of searching they unearthed dozens of previously unknown sources for tracks by Mobb Deep, Todd Edwards and Madlib — enough to make your average sample-reliant producer nervous. Then there are compositional tools that generate entire songs based on text descriptions, like Google’s still-experimental MusicLM, with its uncanny examples of “British indie rock” and “accordion death metal”. Some results are astonishing, while others only serve to demonstrate how messy and subjective our linguistic placeholders are, as anyone who’s participated in a “wat is dubstep” YouTube debate can attest.

MusicLM is still in development, but projects like Sony’s FlowMachines, which gave us the Beatles impression ‘Daddy’s Car’ in 2016, indicate that technologists are obsessed with outsourcing the entire compositional process. You have to ask: what is the imagined purpose of these tools? Are they designed to save time? To make music production more accessible? Or to help artists actually make more interesting music?

Virtual reality researcher Jaron Lanier, an obsessive collector of musical instruments, is suspicious of algorithms that make new songs simply by analysing old songs. “Music is ambiguous: is it mostly a product to be produced and enjoyed, or is the creation of it the most important thing?” he asked in the New Yorker recently. “If it’s the former, then being able to automate the production of music is at least a coherent idea, whether or not it is a good one. But, if it’s the latter, then pulling music creation away from people undermines the whole point.” There’s surely no shortage of people who enjoy actually making music, he adds. “Would you want robots to have sex for you so you don’t have to? I mean, what is life for?”

Bolder musicians are already trying to figure out how AI tools can take us into previously unimagined sonic territory. London audiovisual artist patten recently released ‘Mirage FM’, the first album made with text-to-audio AI samples from Riffusion, a model based on a database of sonograms. The results have a scrappy, lo-fi feel, but patten makes the most of AI’s sonic tics, highlighting uncanny vocals that talk gibberish, Riffusion’s equivalent of DALL-E’s botched fingers. Through text prompts, the model can find the midpoint between otherwise unrelated sounds — what’s between, say, Goa trance and Don Cherry’s trumpet? Ask Riffusion and it’ll spit out a sample that imagines exactly that, despite the impossibility of making the “real” thing.

Neural networks can also be used to imagine sounds from the past. Mexican-American artist Delia Beatriz, known as DEBIT, explored this on ‘The Long Count’, an album that uses machine learning to recreate Mayan wind instruments found at an archaeological site. By transforming a small archive of recordings into a database of frequencies, Beatriz developed a musical palette that could “reconstruct bridges to the past that we have no access to”, in a sci-fi exploration of indigenous culture. She spoke to DJ Mag about the album's creation in 2022.

Holly Herndon’s explorations in AI are well documented. Following her self-built “Spawn” tool, its successor Holly+ is a publicly accessible vocal model which can sing anything you want, a project imagined as an “experiment in communal voice ownership”. (Grimes is doing the same thing with elf.tech, albeit in more chaotic packaging.)

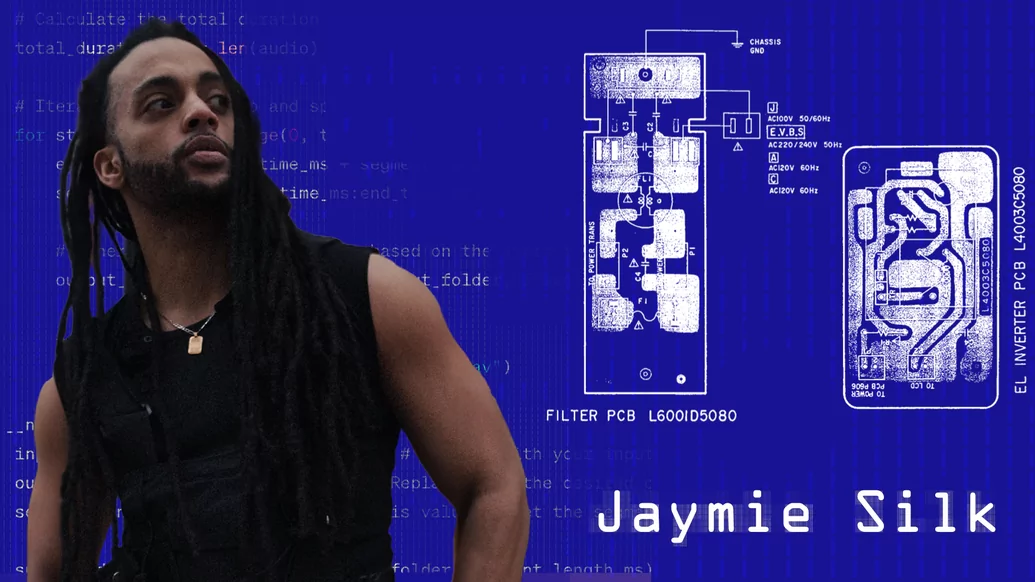

Training your own voice model makes sense if you’re already a singer, but for everyone else there are now accessible “voice swap” tools – surely the future of karaoke? – and text-to-audio deepfakes. The arrival of user-friendly vocal generators raises plenty of questions about copying and authorship, as Paris-based producer Jaymie Silk explored on a recent EP that combines deepfake raps from Kendrick Lamar, Tupac and The Weeknd with tunnelling club beats.

Silk is unapologetic about the fakery. AI “is like a microwave [for when] you don’t want to cook,” he laughs. “I’m not gonna cook no Michelin three-star thing with my microwave. But if I’m like, it would be cool to have 21 Savage on this track, and I don’t want to sample it, I just want two words, I’m gonna do it.”

There’s clearly a big difference between sampling deepfake Drake on an EP called ‘Artificial Realness’ and trying to pass it off as the genuine article. Would any serious artist really want to speak in someone else’s voice and claim it as their own? Regardless, Silk, who has a background in hip-hop, thinks he’s more entitled than most to borrow Tupac’s voice, pitching the EP as a reclamation of Black art in a world where someone like Partyiboi69 gets away with “making ghetto music sampling Black artists”.

Black musical innovation has long been treated as if it’s a common resource, from the Beach Boys lifting Chuck Berry riffs to the success of insipid white rappers like Post Malone. It’s no coincidence that rap has become a playground for AI experimentation, from the ill-fated rap avatar FN Meka (shut down by the label after accusations of blackface) to the oddly satisfying version of ‘Ballin’ rapped by deepfake Homer Simpson and Peter Griffin.

Silk thinks of his record as a grenade thrown by an industry underdog. “If I want to use a sample, I can’t do it, because economically, legally, it’s complicated. But if you’re a big artist you can. So I’m limited in my creativity, but Dua Lipa is gonna use whatever she wants.” Defending the underdog motivates Charnas, too. In a Slate article celebrating 50 years of hip-hop, he called for sampling to be effectively legalised, so that borrowing a part of a recording would work the same way as borrowing the whole song: the rights holders might not like it, but they get paid anyway.

“If I want to use a sample, I can’t do it, because economically, legally, it’s complicated. But if you’re a big artist you can. So I’m limited in my creativity, but Dua Lipa is gonna use whatever she wants” – Jaymie Silk

As it stands, the owners of a recording can charge any price they like for a sample or an interpolation, or simply refuse to licence the music. “I am not uncomfortable with copyright,” he says. “What I am uncomfortable with is when copyright gets in the way of artists’ right to version, and create.” The success of a musical idea can not only be measured by its catchiness or its longevity, but by whether or not anyone wants to copy it. “That’s part of what you are when you’re an author,” adds Charnas, whose own books have been bootlegged and sold on Amazon — annoying, maybe, but still flattering: “As an author, you’re supposed to be quoted!”

Is there another way to encourage creative copying while fairly compensating the artists who come up with the ideas? One solution might be to hand over more power to listeners and fans. Record execs struggling to repeat the profit bonanzas of yore are already starting to understand the fandoms as crucial to their revenue strategy. As Karl Fowlkes, an entertainment and business attorney, put it to Motherboard: “The fan and consumer experience as it relates to music is bigger than the music itself. Fandom is created through experience, concept and the personal relationships that fans have with their favourite artists.”

His theory was tested in April when Travis Scott fans on the Discord server AI Hub collaborated on a 16-track fake album while they waited for the rapper’s new project to drop. ‘UTOP-AI’ managed 170,000 streams in the hours before Warner inevitably issued a takedown. Might it be possible that a major label has misunderstood the potential of new music technology and is seeking to crush user-generated innovation rather than lead the way itself? Who can say. But through the example of ‘UTOP-AI’, we can start to imagine an expanded sense of authorship, rather as Barthes intended, acknowledging not only that the meaning of art is decided by the listener, but that the artist himself is not complete without his fandom.

Doom-mongering pronouncements about the dawn of AI and the takeover of technology can sometimes carry a note of self-fulfilling prophecy. Philosopher Yuk Hui points to the tech industry’s conscious efforts to replace human labour with machine automation, all while “the panicked human repeatedly asks what kinds of jobs can avoid being replaced by machines”. In this struggle against automation, the last remaining human job is, of course, the artist — which is perhaps why technologists are so fascinated by building a machine that can mimic the Beatles. But in Hui’s vision, technology is not our competitor, but a kind of prosthetic that makes us fully human. It shouldn’t reduce our ability to think or create, but expand our potential and liberate us from repetition.

Ultimately it’s up to artists, not engineers and coders, to figure out how to wring creativity from new sampling technology. Just think of the definitive impact of Technics’ 1210s, Roland’s TB-303, or the invention of Auto-Tune — all made iconic through imagination and accident, resulting in the genius of hip-hop turntablism, acid house and rappers like T-Pain and Future. We don’t yet know what we’ll find when we speak through the new machines. The sampling apparatus of the future will need to produce a musical culture that reflects the world we actually live in, with all its mystifying feedback loops and reality leakage.

So, the choice is ours: we can go back to our cheeky edits and forget this ever happened, or we can know the truth about the universe. As Stereotypical Barbie found out, we don’t really have a choice.