A journey through dance music in video games

Dance music and video game soundtracks have had a symbiotic relationship since the '90s, with many electronic artists today still citing the influence of music they first heard on consoles.. With two classic soundtracks just reissued by dance labels, Selim Bulut looks at how club tracks first made their way into games — and how these worlds are more interwoven than ever before

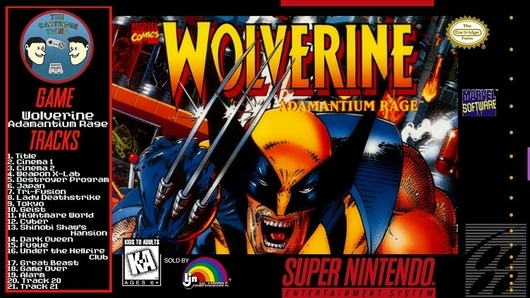

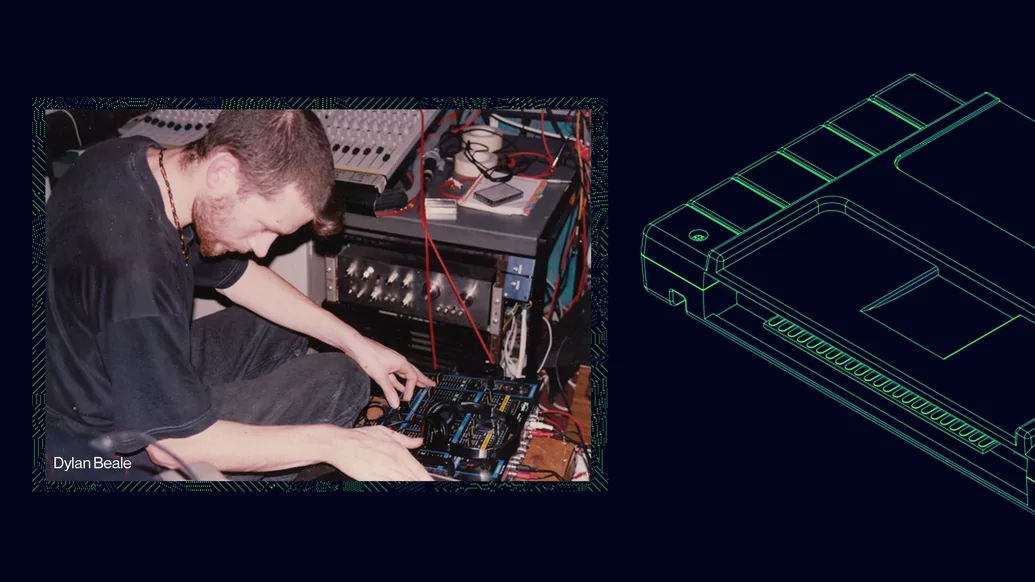

Grime music was not invented by a video game composer from Newcastle back in 1994. But listening to the 'Wolverine: Adamantium Rage' soundtrack, you could almost believe that it was. Adamantium Rage was a Super Nintendo game produced in the early ’90s to cash in on the renewed interest in the Wolverine character following the success of X-Men: The Animated Series. For its soundtrack, UK developers Bits Studio brought in a young musician named Dylan Beale — a newcomer to the games industry, but someone who knew his way around samplers and electronic production as one half of the jungle duo Rude & Deadly. With only limited space for audio on the SNES cartridge, Beale had to get creative. He chose versatile sounds — an orchestral stab, a bass note, and some basic kicks, hi-hats, and snares — and reduced their sample frequencies to keep the file sizes down, resulting in a raw, crunchy, yet surprisingly bass-heavy aesthetic.

Beale tried to impress the game’s US publishers Acclaim Entertainment with a West Coast hip-hop soundtrack, but for the game’s more intense, high-tempo boss fight sequences he pulled from the techno, jungle, and hardcore he’d soaked up at clubs and at the record shop he worked at in Wood Green. “When we played it to the studio, everyone was blown away that you could make a sound like that on the SNES,” Beale recalls today, speaking over the phone from his home in Guildford. Hip-hop, jungle, and techno influences, a restricted sample palette, punchy low-end, gritty sound — when you lay out all those inputs logically, it makes sense that Adamantium Rage sounds a bit like grime before grime. In particular, the boss theme ‘Tri-Fusion’ has all the elements of an early grime instrumental: the skittering drum programming and blunt bass drums of Youngstar’s ‘Pulse X’, those dramatic orchestral stabs like Low Deep’s ‘Cheeky Violin’.

When the track was rediscovered by Brixton grime producer Sir Pixalot in 2016, he highlighted these similarities by sticking an acapella from West London MC J-Wing over the top, while another producer followed suit by adding Tempa T’s 'Next Hype' vocal to it. They fit like a glove. “Once you put an acapella over the top, it fucking works,” says Beale. “When [Sir Pixalot] did that first one I must have listened four or five times, just laughing, because it was so perfect. This thing that I spent hours and hours doing — never, ever had I imagined someone rapping over the top.”

“When we played [the soundtrack] to the studio, everyone was blown away that you could make a sound like that on the SNES” – Dylan Beale

Beale’s ‘Adamantium Rage’ soundtrack was recently remastered and reissued in a double-vinyl package by modern hardcore and club label Sneaker Social Club. It’s not the only such soundtrack to catch the attention of dance music fans: Barcelona’s Lapsus Records also put out 'wipE'out'' – The Zero Gravity Soundtrack', a three-LP version of the original tracks created for high-octane PS1 racer Wipeout. Over the past few years, video game music (VGM) has flourished in the reissue market, with everything from the NES classic Castlevania to the modern blockbuster The Last Of Us getting a physical release.

This trend has coincided with a growing awareness of just how poorly preserved gaming history is, with source codes lost to studio mergers and acquisitions, copyright laws putting the ownership of titles in legal limbo, and many games unplayable due to obsolete technology. Without the right care or attention, their soundtracks would also be forfeited to time — and in the case of dance music, that would mean losing access to a fascinating region of the genre’s history that producers and DJs are still only beginning to explore.

Electronic musicians have been interested in video games since the 1970s, when Yellow Magic Orchestra sampled tunes from Circus, Space Invaders, and Gun Fight. VGM’s 8-bit and 16-bit eras created plenty of accidental club bangers, from Beale’s ‘Adamantium Rage’ soundtrack, to the proto- dubstep of NES game Overlord or the borderline Drexciyan final boss music of the Sega Mega Drive’s Fatal Labyrinth. Some of the most surprising and unusual of these have been presented by New Zealand journalist, DJ, and researcher Nick Dwyer in his Diggin’ In The Carts radio show, its accompanying 2017 compilation for Hyperdub, and 2020’s Teki And Nick’s Mixtape Quest Adventure, a b2b mix with Teki Latex that found a connective tissue between DJ Lag, OutKast and Yasunori Mitsuda’s ‘Chrono Trigger’ soundtrack.

But even in gaming’s early days, there were some more deliberate crossovers with dance music. The 1989 Amiga and Atari ST game Xenon 2: Megablast took its subtitle from a Bomb The Bass single, and featured an arrangement of the track as its theme music. The Mega Drive’s Streets Of Rage series, which debuted in the first half of the ’90s, is as famous for its house and techno soundtrack as it is its beat-’em-up gameplay, with composers Yuzo Koshiro and Motohiro Kawashima hearing the sounds of Detroit, Chicago, and Berlin on the dancefloor of Tokyo club Yellow and recreating them with the console’s Yamaha YM2612 sound chip.

“I love the early game music, when it sounded like nothing else due to the constraints of the hardware and the ingenuity of the composers,” says Steve Goodman, aka Hyperdub boss Kode9, who co-curated the Diggin’ In The Carts compilation with Dwyer and who contributed a new remix to the recent Wipeout reissue. “As the tech evolved, there was no longer anything so unique about game music due to technical constraints, so you got music from everywhere coming in. There was a lot of influence from dance music in the ’90s.” Indeed, the transition from cartridges to compact discs with PC gaming and Sony’s first PlayStation console in the 1990s meant fewer technical limitations to what a game could achieve with audio.

In Japan, that meant a number of novel music and rhythm games like Vib Ribbon, PaRappa The Rapper, Bust A Groove, and Dance Dance Revolution. In the UK, Sony sought to shake off gaming’s nerdy or childish image by deliberately aligning themselves with dance music and club culture. The two mediums already crossed over in the 1980s and early ’90s, when nightclubs would close at 2am, as Dylan Beale explains. “People would want to go to someone’s house after, generally trying to chill out, wanting to stare at something, and often someone would have a Mega Drive or SNES,” he recalls. “You’d listen to music or play video games. Some would put records on and play video games with no music. The two things started to merge.”

All Sony had to do, then, was make this connection explicit. They targeted the young adult market with edgy advertisements directed by Aphex Twin collaborator Chris Cunningham, PlayStation chillout lounges in clubs like Ministry Of Sound stocked with unreleased games, and youth culture crossovers like Lara Croft ‘wearing’ Alexander McQueen on the cover of The Face magazine. Games at this time often had high-fidelity soundtracks of big beat, techno, progressive house, drum & bass, and trance — the thwacking kicks, looping breaks, and rising filter sweeps a futuristic fit for the PlayStation’s 32-bit processor and graphics hardware.

Crucial to this image was Wipeout, the slick anti-gravity spaceship racing game released on the PlayStation’s European launch. Developed by Liverpool studio Psygnosis, the game boasted a hypermodern look and feel with creative direction by The Designers Republic, known for their work with Warp Records. But it was the soundtrack that has stayed in people’s imaginations. Making the most of advanced audio, the game featured officially licensed tracks by The Chemical Brothers, Leftfield, and Orbital, bulked out with a number of tracks by an unknown artist called CoLD SToRAGE. Tim Wright had worked at Psygnosis as an in-house composer and sound artist for a few years when the Wipeout brief came in. Prior to that, the Welsh musician was perhaps best recognised for his work on Lemmings (a rush job, by his own admission). While many of his colleagues at the company were clubbers and dance music obsessives, his interest was ’80s synthpop.

“I love the early game music, when it sounded like nothing else due to the constraints of the hardware and the ingenuity of the composers.” – Steve Goodman, AKA Kode9

“I was more into being a nerd at home,” Wright says, speaking from his current home in Switzerland. “Computers and music, and going to clubs to do that — computer clubs,” he clarifies. Wright might not have been a clubber, but he was a fast learner. For his previous project, the first-person shooter game Krazy Ivan, he had to get his head around industrial music and musique concrète in a matter of weeks, all while learning how to produce CD audio, having previously worked with sound chips. Still, his early ideas for Wipeout were too melodically complex, so his colleagues took him out to Cream at Nation to get a feel for the music in the right setting. “I didn’t know how that [dance] music worked. Some of my tracks were like seven songs glued together,” he says (though adds that he’s since grown to love genres like trance).

After leaving Psygnosis, Tim Wright launched a new studio called Jester Interactive with a game series, Music (or MTV Music Generator in North America), that would be just as influential in dance music. Functioning like a quasi-DAW, the game introduced young people to the basics of looping and sequencing before they eventually graduated onto software like Fruity Loops. “Future Music magazine put me on the cover [after its release], which was mind-blowing,” says Wright. “I was talking to the editorial guy and they said, ‘Any ideas for the strapline?’ I said, ‘I’ve just got the sales figures’. So the strapline was: ‘I’ve turned a quarter of a million gamers into musicians’.”

Some producers, like Skream, Hudson Mohawke and Karen Nyame KG have said that the sequel Music 2000 was their introduction to making music, while a 17-year-old Benga demonstrated how to make a grime loop on the game in a 2003 radio documentary. By the end of the ’90s, a diverse range of dance music had found its way into games, from Buck Bumble (speed garage, rather than “boring techno stuff”, as Justin Scharvona, the head of music at developers Argonaut, told 64 Magazine at the time) to Ape Escape (whose sparkly drum & bass tracks were made by Japanese house producer Soichi Terada).

Russell Shaw worked in recording studios in the 1980s and ’90s, and when his studio hired Morgan Khan, founder of the highly influential ’80s dance label StreetSounds, he found himself producing white label dance 12-inches aimed at the club circuit before moving into the games industry. In the late ’90s, he started working on a god simulator called Black & White, which featured an ambient techno soundtrack that changed dynamically with the player’s movements. “Plaid, Autechre, Squarepusher, Boards Of Canada — how those guys used to approach EQ, their reverbs, and their mixing gloss, I used to love how I’d be hearing sounds I’d never heard before,” Shaw explains over Zoom. “You could tell they spent a lot of time thinking about sound as well as composition. I wanted Black & White to be like that. There weren’t a lot of games at the time doing this.”

Licensed soundtracks had been around since the 1990s, particularly in games like the FIFA series, but as technology improved and budgets swelled in the 2000s and ’10s, they became a bigger draw for Triple-A titles. Countless musicians have been inspired by the dance music radio stations of the Grand Theft Auto series (the game even added a clubbing element, rendering real- life DJs like Moodymann, Palms Trax and The Blessed Madonna in GTA Online). SHERELLE has said that the prevalence of jungle / drum & bass on PlayStation titles, particularly the soundtrack of FIFA Street 2 and the Moving Shadow catalogue featured on Grand Theft Auto: Liberty City Stories, had a huge impact on her own career.

Today, gaming culture and electronic music are quite intricately linked. Even broadcast and communication channels like Twitch and Discord, which have increasingly been adopted by DJs, producers and radio stations, have their roots in gamer culture. “I recently created a Game Boy video game featuring 8-bit alternative versions of my album tracks,” says French producer Simo Cell, who remixed CoLD SToRAGE’s ‘Trancevaal’ for the new remaster. “We even launched a speed-run contest, where the first player to complete the game earned a lifelong spot on my guest list for all future club shows.”

“No matter what kind of dance you’re talking about — electronic music, modern dance, ballet — because so many games are about movement and action, the music connections are everywhere.” – Lena Raine

Lena Raine, whose discography includes delicate melodic music for Celeste, Minecraft, and Guild Wars 2 as well as an album that was remixed by techno producers including Anastasia Kristensen, describes why dance music and games are a “perfect fit” for one another. “There’s an emotional flow: the risers, drops, and breakdowns all correlate to some sort of emotional resonance that is also felt in the way games frame the emotional journey of their design,” she says.

“When you’re deep in the flow of playing a game, the way you’re challenged is like learning to dance. You’re reacting to what the game is throwing at you and replying with all the moves you’ve learned, and that interplay is where you find yourself conversing with a game. Writing dance music is the perfect kind of accompaniment to those exchanges, because it can flow around your movements in the game and react to how you’re playing; how you’re feeling. No matter what kind of dance you’re talking about — electronic dance music, modern dance, ballet — because so many games are about movement and action, the music connections are everywhere.”