How Souls Of Mischief's ‘’93 ’til Infinity’ inspired a new future for hip-hop

30 years after their debut, four rappers from Oakland, California, remember how they became one of the first crews on the West Coast to make a particularly conscious, lyrical strand of hip-hop, with an album that influenced generations of artists

In February 1992 a bunch of industry bigwigs showed up in San Francisco. They were there for the Gavin Seminar, a showcase of West Coast musical talent where big money deals were made. Journalists, PRs, radio programmers, DJs and A&Rs from just about every record label in the business — Columbia, RCA, Death Row, Loud, Jive — were there. Passes cost $500.

Anyone who was anyone was staying at the Westin St. Francis hotel, where a constant stream of label execs would flood through the lobby. Until they couldn’t: with the convention in full swing, access to the hotel elevators was blocked by a group of kids. There must have been a dozen of them, seemingly all teenagers, and they were rapping and beatboxing so anyone trying to get through the lobby had no choice but to listen.

“Well, the passes cost a lot of money, so if you didn’t know somebody, or make a fake one, or have the money to pay for one...” says A-Plus, remembering freestyling at the Gavin with the other three members of Souls Of Mischief and their extended family, the Hieroglyphics crew. “If you’re a bunch of kids who didn’t have passes, you know there’s gonna be a lot of activity at the hotel. So, if you wanted to get some attention, that’s where you went.”

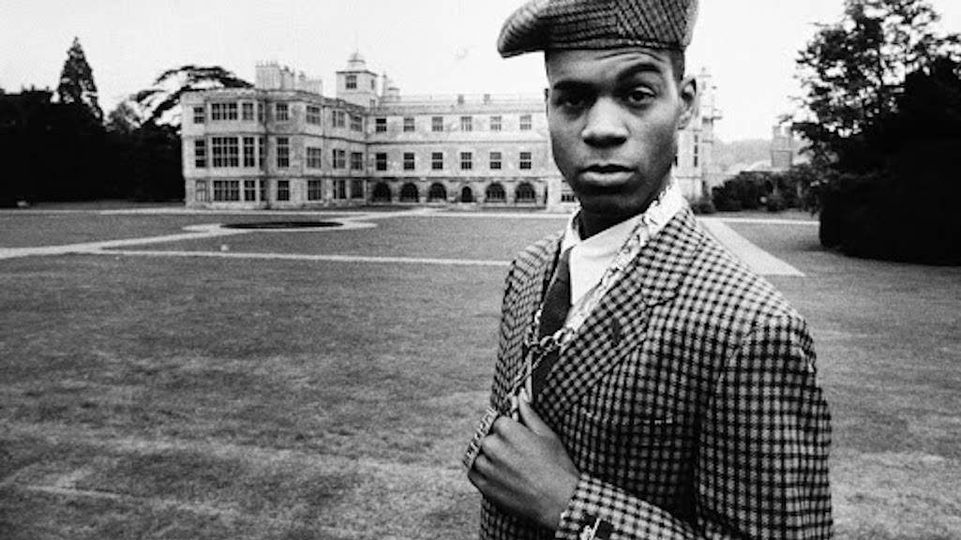

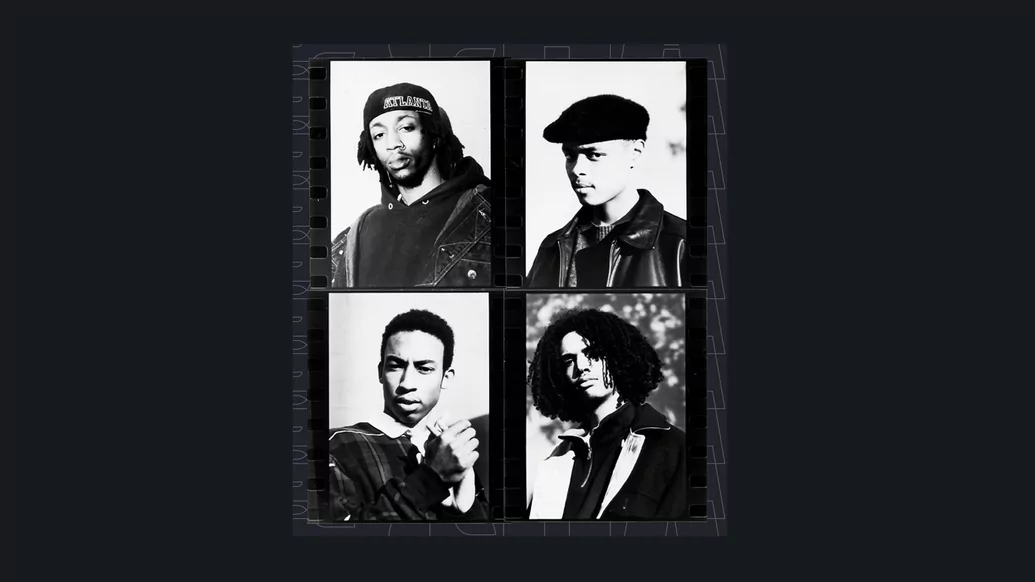

In 1992, A-Plus, Tajai, Opio and Phesto Dee were 16, and had just started calling themselves Souls Of Mischief. Their friend and fellow Hiero crew member Teren Delvon Jones, better known as Del The Funky Homosapien, was two years older than them and had recently signed a deal with Jive Records. With this connection, a few recorded demos, and the buzz generated by their cypher stunt at the Gavin, Souls soon became one of the hottest new acts in hip-hop.

“Back then, there was no internet,” adds A-Plus. “So word of mouth was the best way to transmit information. You make a scene at the Gavin, word’s gonna spread.” A bidding war ensued. Legendary DJs, hip-hop tastemakers and A&Rs Stretch and Bobbito wanted to sign Souls to Big Beat; Atlantic were also interested. But Jive already had Del, Too Short, KRS-One and — Souls’ kindred spirits — A Tribe Called Quest on their books. Their signing was a formality. Or it should have been.

With help from Opio’s stepdad Michael Ashburne, an attorney whose previous clients included Richard Pryor, Souls negotiated an unprecedented deal that meant they kept their publishing rights. “That was a huge, huge, huge deal,” says former Jive exec Sophia Chang in Shomari Smith’s 2013 documentary Til Infinity, adding: “For kids that young, I think it was a little egregious.”

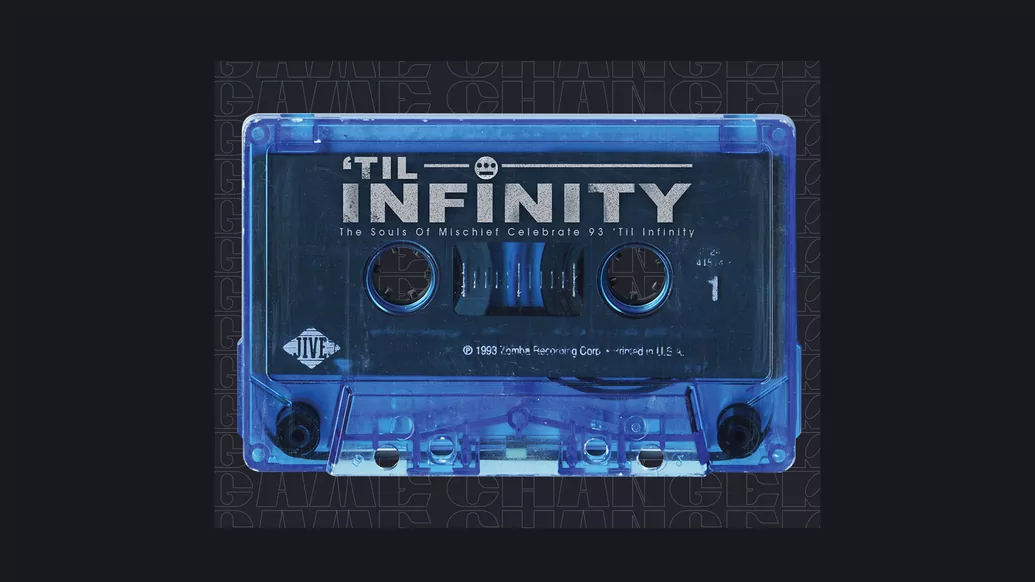

Souls recorded ‘’93 ’til Infinity’, a masterpiece of lyrical hip-hop with beats that bled soul and jazz samples like they had the stuff pulsing through their veins, 14 songs of unadulterated perfection narrated by four MCs connected like sherpas roped together on a mountain. In 1998, The Source magazine named ‘’93 ’til Infinity’ among the 100 greatest hip-hop albums of all time and, in its title track, Souls had a song that would live forever. 30 years later, the four of them — now 47 — sit in a hotel in Camden before playing the Jazz Cafe, part of a 93-gig tour celebrating the anniversary.

A-Plus and Tajai initially met at school in Oakland and recorded their first song as kids in the studio of Sir Jinx, an LA producer and rapper, Dr Dre’s cousin and — in the ’80s — a member of the C.I.A, Ice Cube’s pre-NWA rap group. Phesto entered the Souls picture in junior high and Opio completed the set a few years later. “I was happy to meet somebody that was into hip-hop as much as I was,” Opio says. “I could count the number of people that were really into it on one hand before I met them.”

One of the first things they wrote together was ‘Cab Fare’, or ‘Taxi’, as it’s often known, owing to the sample of Bob James’s theme from the late ’70s sitcom Taxi. The sample was never cleared, meaning the song only exists to those who know how to find it, but it captures the Souls magic exquisitely. Angelic keys and a flute twinkle, as Souls rap about the tribulations of a cab driver, two from the perspective of a cabby, two as passengers. There’s nuance, narrative and a comedic edge. “I’d drive a blind man around for a while, even if he only had to travel just a mile, with a smile,” raps A-Plus.

In the early ’90s, so-called alternative hip-hop was gathering steam. De La Soul and Tribe had both released successful albums dense with complex lyrics and rhyme schemes, a yang to the yin of gangster rap. But they were from New York. In the west, NWA, Ice-T and Cypress Hill dominated the airwaves, with songs about gang-banging, drug dealing or altercations with police.

“Who else died besides Pac and Biggie? In this big beef between two coasts, everybody's got guns in scary America, who else died? Nobody. Who else got beat up? Who else got their car keyed? Literally nobody.” — TAJAI

“We had this stigma of being from somewhere where lyrically, people were supposedly inferior,” says Tajai. A-Plus finishes his sentence: “...and that stigma was created by record companies. It was the gangster gold rush for the greedy record industry. Somebody struck gold with NWA and it was this big sensation and so the ignorant record companies that don’t know nothing about nothing just wanted to go find more gangster rappers, so it gave the impression to the rest of the world that there was nothing on the West Coast but gangster rappers.”

Every member of Souls Of Mischief could rap (at least) as well as Tribe’s Q-Tip and Phife Dawg, bringing new levels of wordplay and social commentary to California. Their backgrounds were clearly different to their gangster rap contemporaries, but their edge never left them. Soon after they signed their deal in 1992, they were interviewed at a Jive event, bristling with youthful exuberance. “It’s something you never heard before,” a teenage A-Plus declared into a mic. “We here to build bridges and... wreck shit.”

They piled into a studio and hit record. “We were doing two or three songs in the course of like five or six hours,” says Opio. “I don’t know if I’ve ever been that focused in the studio.” Sometimes they wrote lyrics at home, sometimes they wrote them together in the studio. “We’d be sitting around and somebody’d be like, ‘Hey, what rhymes with...?’” A-Plus remembers. “Or like, ‘How does your line end, so I know how to start my line?’” says Phesto. “I feel like it was also so we didn’t say the same shit.”

They seemed to breathe collective energy, but each of them had their own assets. In Til Infinity, West Coast spinner DJ Apollo describes the Hieroglyphics’ rapping technique as the “connect-the-dots style... this syllable will rhyme with that syllable. A-Plus is like the master of the connect-the-dots style.”

Many considered Phesto the most complex rapper — “you gotta really listen to what he’s saying,” as Souls’ former DJ Lex says in the doc — while Tajai was lots of people’s idea of the energy man, a confident speaker who “would have been a brilliant writer if he had decided to be a novelist,” said journalist and author Joan Morgan. With his big hair and left-field charisma, Opio was Souls’ George Harrison — and Phife Dawg’s favourite.

Contrary to the violent image painted of California on NWA’s ‘Straight Outta Compton’, Souls Of Mischief spent much of ‘’93 ’til Infinity’ spreading a message of peace. But they stopped short of hippiedom. On ‘Live And Let Live’, Opio raps: “Not a murderer, ensuring the longevity of my life, I’ll live and let live, kill if I must, I shall”. “I mean, situations with bullets flying happened a lot,” says Phesto. “If you went out in the Bay Area during that time, it was highly likely that there would be some type of hellfire.” When Biggie Smalls was assassinated in LA in 1997, six months after the murder of Tupac Shakur, it was spun as the tragic nadir of a war between America’s two seaboards. But Souls say this was an exaggeration.

“My thinking was, we’re done... Pep’s up next. I wasn’t thinking, ‘This is gonna be a hit’, I wasn’t thinking nothing.” — A-Plus

“There was no real East-West-Coast beef,” says A-Plus. “That is a facade that the media made. It was a beef between a faction of people from the West Coast and a faction of people from the East Coast, based offa some personal shit between Suge Knight and Puffy Combs.” Tajai asks: “Who else died besides Pac and Biggie? In this big beef between two coasts, everybody’s got guns in scary America, who else died? Nobody. Who else got beat up? Who else got their car keyed? Who else got hit with an egg? Literally nobody. Nobody got their feet tickled. Nobody put some pepper in somebody’s nose and made them sneeze. It’s complete bullshit.”

As if to pacify any notion of violence, Tajai ad-libbed an immortal Souls manifesto on the ‘’93’ title track: “Sometimes it gets a little hectic out there, but right now, yo, we gonna up you on how we just chill.” The track ‘’93 ’til Infinity’ had existed for a couple of years in its lyrical form and was initially known as ‘’91 Til Infinity’. But the beat, produced by A-Plus, never found its way into the rest of the group’s ears until the album was almost done. In fact, A-Plus originally earmarked it for fellow Hiero rapper Pep Love.

“My thinking was, we’re done,” A-Plus says. “Pep’s up next. I wasn’t thinking, ‘This is gonna be a hit’, I wasn’t thinking nothing. I was just like, ‘Hmm, Pep would sound good on this’.” But with most of the album finished, Souls still had about half an hour left of their studio session, so A-Plus played the instrumental, a sped-up sample of ‘Heather’ by Billy Cobham. It was so good the group made a rule that from then on, A-Plus had to give them first dibs on any beat he made. “They was like, ‘You can’t be doing that no more. We in the middle of making an album, you can’t just be giving beats away!’”

They wrote ‘’93 ’til Infinity’ on the spot and were finished within a few hours. It became their biggest hit and went on to become a rap classic, later inspiring freestyles from Freddie Gibbs, J. Cole and Big K.R.I.T., plus Joey Badass’s tribute ‘’95 Til Infinity’. Watch Shomari Smith’s documentary, and you’ll also see love shown to Souls by E-40, Prodigy, RZA, Snoop Dogg, Killer Mike and many more hip-hop hall-of-famers.

Souls released one more album on Jive, the underrated ‘No Man’s Land’, but received little commercial backing. A-Plus says the label asked them to make their next record sound like Jazzy Jeff and the Fresh Prince. So they ditched Jive and, ignoring offers from elsewhere, went independent. They’ve stayed that way ever since. “We talk about this every night,” says Tajai. “30 years out, 28 years independent.”

Playing the Jazz Cafe, Souls rap every bar from their debut album with vim, finishing each other’s lines with the same energy they had as teenagers. “We market it like it’s a big tour, but we’ve been doing this the whole time,” says Tajai. “Because we’re not on TV, we’re not on the radio, so we have to tour. But as a result, we go to these shows and everybody is 19.” He’s right — more or less: a young crowd (at least younger than 47) laps up everything they throw down. Phesto is already looking ahead to their next big birthday: “30 years is a bigger deal than 20 years, and 40 years will be a bigger deal than 30.” We hope they make it that far (“Shit, so do we,” says Tajai), but their debut album will live forever, ’til infinity and beyond.