Gabber at 30: hard, fast, and louder than ever

Dutch gabber erupted from localised scenes in Rotterdam and Amsterdam, evolving into one of Holland's most significant youth movements of the ’90s. But its mass popularity was also its downfall, and by the millennium the scene had collapsed. Here, Holly Dicker looks back at 30 years of gabber, finding that artists outside of its home country have recently helped foster a wider interest in the sound, as well as speaking to those pushing a more diverse and enriched new-meets-old gabber scene in Holland

It's 3PM on 1st July in South Holland. Under a thunderous sky at Crabbe Park in Vlaardingen, a short metro ride from Rotterdam city centre, the second edition of Parkzicht Outdoor is well underway. For nearly three decades, Parkzicht, Rotterdam's most (in)famous discotheque, has endured in exile, ever since it was closed by former city mayor Bram Peper following a series of shootings in 1996. Within the dungeon-like bowels of this 1900s stately villa, nestled in the shadow of the city’s most recognised landmark, the Euromast, a wild and harder-edged form of dance music evolved throughout the ’90s, free from exclusionary door policies or musical boundaries.

“Parkzicht was our Haçienda,” says Rob Fabrie, AKA Waxweazle. “It was hard-edged because of the Rotterdam spirit: we are not bullshitting around.” Parkzicht was not solely a “gabber cave”, as Rotterdam 'Godfather’ Paul Elstak insists in VPRO’s three-part documentary, 30 Years of Dutch Dance. “But at the end of the night, we hit the gas,” he enthuses. The original Parkzicht sound was eclectic, with residents Ricky da Dragon playing mellow at one end, and DJ Rob with his three decks and 909 at the other, pushing a harder and more distorted style on Friday nights. At this year’s festival, they open and close the Parkzicht area, backdropped by fresh illustrations from the club’s cartoonist Kees Linia, with sets in between from Belgium pioneer Franky Jones, local legend Lucien Foort from Quadrophonia, and the ever-entertaining Darkraver from The Hague.

Dutch gabber erupted in the early ’90s from localised scenes in Rotterdam, around clubs like Parkzicht, and illegal warehouse raves in Amsterdam, and was exported to cities like London, Berlin, New York, Rome and Glasgow, where diehard gabber communities formed. Gabber — originally known as gabberhouse in the Netherlands, and seen as a subgenre of house — was music for the people, named by Amsterdam’s clubbing elite as a diss; but the gabbers — a term used for fans of gabberhouse — embraced it and made it their own (more on that later).

“1996 was a special year. We talk about the [second] summer of love in 1988; I think 1996 was that for gabber.” — Waxweazle

Gabber is characteristically hard, fast, and loud rave music, made with distorted drum machines and sampled hooks to keep you chopping in the Hakke dance all-night long. Gabber would evolve into one of Holland's most significant youth movements throughout the ’90s, spawning a subculture with its own uniform look of shaved heads, Nikes and colourful, expensive Australian-brand shell suits. Mega raves like Thunderdome later helped push gabber into mainstream popular culture, but gabber’s mass popularity was also its downfall. By the millennium the scene had collapsed, and was rebranded as hardcore. But gabber never went away. Not really. And in recent years it has been making a comeback.

At Parkzicht Outdoor, Fabrie opens the A Nightmare area with his signature style of dark-happy hardcore as Waxweazle, next to a billboard slashed by giant bloody Freddy Krueger finger blades. A Nightmare is Paul Elstak’s original gabber brand, which launched at Parkzicht on 4th December, 1992, and developed in noisy symbiosis with his Rotterdam Records label.

Before gabber, Elstak was a hip-hop DJ and in 1990, when Fabrie was just 17, they made their first hip-hop meets house record together with Richard van Naamen as Holy Noise. The group broke through one year later with their ravey sample-heavy hit ‘James Brown Is Still Alive’, a timely rebuttal to L.A. Style’s ‘James Brown Is Dead’, which was at the time flying off the shelves of Mid-Town Records on the Nieuwe Binnenweg — one of the most important record shops in the Netherlands, where Elstak worked. Fabrie sacrificed school to tour with the band alongside rappers Alee and MC Ruffian, as well as dancers Erwin Girigorie and Natasja Morales, including a trip to New York to play the legendary Limelight.

One year later, Fabrie, Elstak and van Naamen inaugurated Rotterdam Records as Euromasters with the controversial opening salvo, ‘Amsterdam Waar Lech Dat Dan?’. Parkzicht cartoonist Linia’s cheeky Euromaster character adorns the cover, destroying Amsterdam in a spray of golden piss. Defined by local pride — a Rotterdam trait still true to this day — the record paved the way to the merciless and heavily distorted gabber sound Rotterdam Records would become globally renowned for, captured best in Elstak and van Naamen's ‘Rotterdam’ EP as Bald Terror, released in 1993.

This was not techno, which at the time meant Speedy J and Stealth Records in Rotterdam, and Plus 8 straddling Windsor and Detroit, who all briefly crossed paths at Parkzicht, before the gabber craze took over. At Parkzicht Outdoor there’s a tiny third stage paying tribute to Rotterdam techno, looking more like a pig shed with a simple strip of coloured LED lights illuminating the DJ booth. Cynthia Spiering is the star here, playing fast techno into an hour of buoyant and bouncy gabber as day transitions into night. As a 20-something techno DJ, Spiering is an outsider to the scene, only recently playing gabber sets at techno parties like Verknipt in Amsterdam and her own Courtoisy night at Rotterdam’s Now & Wow club.

Original gabbers — who make up the majority of the Parkzicht Outdoor crowd — might question her motives: is she riding the gabber train now because it’s cool in the hard, fast techno scene? Nevertheless she smashes it, digging deep and playing with genuine enthusiasm, and keeps the crowd dancing ’til the end. More crucially, Spiering is bringing gabber to a newer, broader audience — a move Gabber Eleganza helped instigate with his archival blog, launched in 2011, around the time the early hardcore gabber revival started. Now the Italy-born, Berlin-based post-rave DJ is performing his The Hakke Show with gabber dancers on cult festival stages like Dour, and played gabber in front of 300,000 people during July’s Rave The Planet Parade in Berlin.

Over the last decade, outside of the Netherlands, gabber has returned as a hybridised ‘post-Net’ sound, freely merged with other music styles by producers and DJs raised on Discogs and SoundCloud. Major platforms like Boiler Room and its Hard Dance portal have helped these niche reinventors like Casual Gabberz and Wixapol gain worldwide traction, inspiring a more recent flourish of all-female harder styles collectives like Explity in Paris and Belgium crew Burenhinder. “It’s important for us to build bridges between different musical genres,” explains Explity co-founder KimberlaiD, who launched their label, Explity Music, at the start of the year with a sweetly distorted compilation of club bangers and home listening music written by 31 women from around the world. “As someone said, God is a Girl Gabber,” she continues, “and we want to make room for gender minorities in the industry: we’re more and more visible, but still not enough.”

In The Netherlands, there’s a more purist revival happening around early hardcore brands like Rotterdam-based This Is Madness, who have been hosting authentic gabber parties in smaller clubs across the country since 2015. Their latest event, Gabberboot, is a hardcore cruise down the Nieuwe Maas river featuring a line-up of rising homegrown talents like original Rotterdam gabber Lady Error.

“It’s not a way of life, it is my life.” — Lady Error

“I really want the new generation to get that old pure hardcore gabber feeling through my music,” says Leonie, AKA Lady Error, who went to her first gabber rave at the Energiehal, in 1992, aged 14. For Leonie, gabber was “a way out of reality”. She’s one of the most well-documented gabbers in the Netherlands, featured in the notable gabber TV documentary, Lola Da Musica, which aired in 1995. Leonie is also the first Gabberbitch in Ari Versluis' iconic tiled street style photo series of girl gabbers. Her blond hair is tied back in blue, white and red bands, revealing a classic undercut and ears choked in gold rings. “I still know a lot of them,” she says about the other girls in the series, “and they’re all still raving.”

For Leonie gabber was — and still is — relief from the daily grind; a diehard community who needed the music, and each other, to get through the week. “In the past a lot of gabbers had problems and a lot of shit,” she continues. “So we went to a party, and we only went for the music. It’s still the same today. If I didn’t have hardcore or gabber, maybe I wouldn’t be here anymore.”

“Gabber is an Amsterdam Yiddish slang word,” explains Ilja Reiman, founder of Amsterdam gabber crucible, Multigroove, about the origins of the term, which means mate or friend. “People from [house club] the RoXy called us this as a swear name: the gabbers are not allowed in. And we said, fine, we are the gabbers. We embraced the name.” But for others, like Fabrie in Rotterdam, gabber was a diss, which 30 years later hasn’t lost any of its sting. “I think gabber is a shitty term,” he says. “I know it means friend, but I still remember why they said it: to diss the music that we made in Rotterdam, so I’m always saying I’m hardcore.”

Rotterdam Records released Euromasters' ‘Amsterdam Waar Lech Dat Dan?’ over 30 years ago in response to “not being recognised” by the Amsterdam scene. Its B-side track ‘F..K DJ Murderhouse’ is a direct reference to the Amsterdam DJ and music critic Ad De Feijter AKA DJ Murderhouse who “trashed” Holy Noise in a magazine review. The EP launched Rotterdam Records in April 1992 with a strong MO: We are Rotterdam! (a rough translation of the typical Rotterdam expression titling the other B-side track, 'Rotterdam Éch Wel!') On the same month of this release, Amsterdam’s gabber incubator, Multigroove, began its historic run of illegal parties, which took place over consecutive weekends at Elementenstraat, back when gabbers “had long hair and dressed in nice white shirts and housey clothes,” continues Reiman. “Bald heads and Australians came later.”

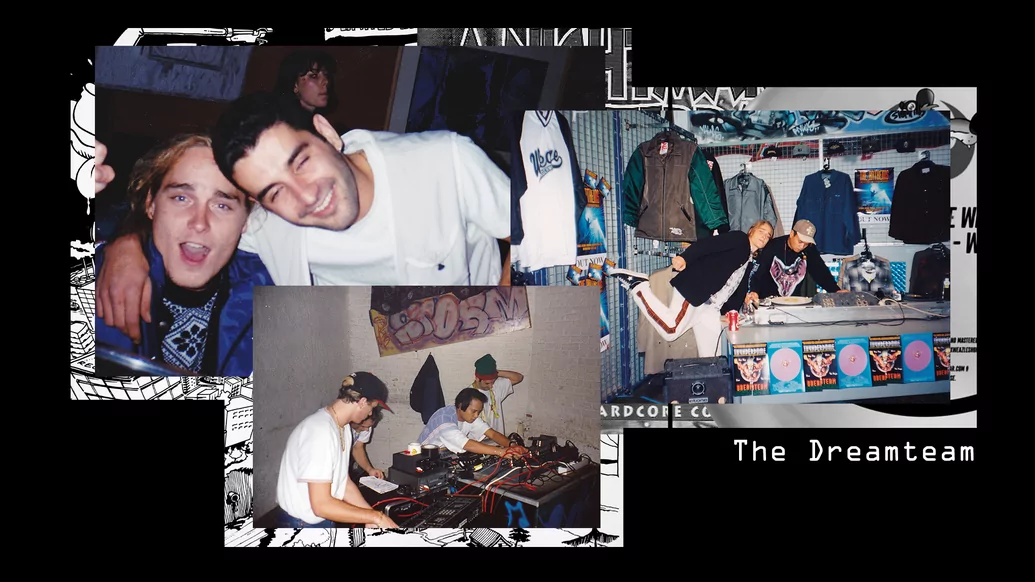

At Multigroove, local DJs The Prophet, who much like Elstak came from hip-hop, swingbeat DJ Buzz Fuzz, who worked at the Attalos record store, and DJ Dano, who had been playing and releasing acid machine jams since 1990, formed The Dreamteam. They became The Netherland’s first hardcore supergroup, with fourth member Gizmo joining later. Mokum Records — also born on the Multigroove dancefloor — was Amsterdam’s more experimental answer to Rotterdam Records, with tracks like Dano's mental and accelerated ‘Cosmic Trash’ and ‘De Skippybal’ launching Mokum in 1993.

By this point “the craze had taken over”, explains Fabrie. “We opened the SL1200s and turned up the pitch so it gets two times as fast. But I wasn’t really into that.” As the scene kept getting harder and faster, happy hardcore emerged as a poppier alternative, with Fabrie rising to prominence with his darker version of gabber meets UK breakbeat rave, which he curated on his own Waxweazle label from 1994.

Both Mokum and Rotterdam Records experienced huge commercial success in this period: Mokum with signings like British act Technohead; Rotterdam Records with Elstak’s series of chart-topping happy hardcore hits, including ‘Luv U More’, ‘Rainbow In The Sky’ and ‘The Promised Land’ (all written by his Mid-Town Records colleague Koen Groeneveld from Klubbheads). Happy hardcore signified gabber’s transition into popular culture, and by the mid-’90s gabber was at its peak. “1996 was a special year,” confirms Fabrie. “We talk about the [second] summer of love in 1988; I think 1996 was that for gabber.”

This was when the biggest Thunderdome of the ’90s took place at the WTC Expo in Leeuwarden on 20th April, under the banner of Dance or Die! Three months later, Fabrie and other Thunderdome DJs were in Berlin playing gabber and happy hardcore to 750,000 people massed at the Kurfürstendamm for the Love Parade. “That was probably the moment where we had those one million gabbers running around,” Fabrie continues. But the high wasn’t to last: “Gabbers were in the street and proud, and then when those shitty parody records came out they were being laughed at. It created a lot of anger.”

With gabbers being ridiculed by parody acts like Hakkûhbar (featuring Amsterdam critic Ad De Feijter as one of its members), exploited by brands, and generally demonised in the media, going into the millennium many chose to quit the scene — artists and fans alike. “It did not collapse all the way, though,” says Leonie, who stayed a gabber throughout, “it just went really underground. My hair was longer and I didn’t wear Australians anymore, but I never stopped listening to the music.”

After the gabber scene collapsed, it was reborn as hardcore, a catchall term now covering a wide range of harder styles music, from sludgy doomcore (at 60 to 140BPM) to the goofy-aggressive terror (from 190 up to 300BPM) and faster, harsher speedcore (300BPM+). In the Netherlands, these are more than mere musical styles, they represent separate scenes and tribes, each with their own infrastructure of events, artists and labels. But Gabber doesn’t quite fit into this contemporary hardcore hierarchy.

“Hardcore is for everyone, gabber is not,” explains Daniel Rønhave AKA Peckerhead from Copenhagen, a child of the ’90s who’s been flying the flag for contemporary gabber at home in Denmark since 2010, and in the Netherlands as a mainstay of Mokum for the last six years. “Gabber for me is the unity and friendship of all the people I’ve met in this subculture,” Rønhave continues. “It’s people I trust in good times and bad times, in crazy situations and steady ones. It’s the ultimate connection you can have, where there’s no borders, no countries, no limits.”

In his productions, Rønhave mines the past with steeped passion and sensitivity, adding his own “Danish trancy hardcore” signature, as he describes it. The resulting records convey an oldschool gabber spirit, brought chopping and screeching into the present. Whilst there are some introspective moments on his current debut album for Mokum, titled ‘Dreams & Doubts’ — in reference to feeling like a “tourist” in the Dutch gabber scene — this music comes alive on the dancefloor.

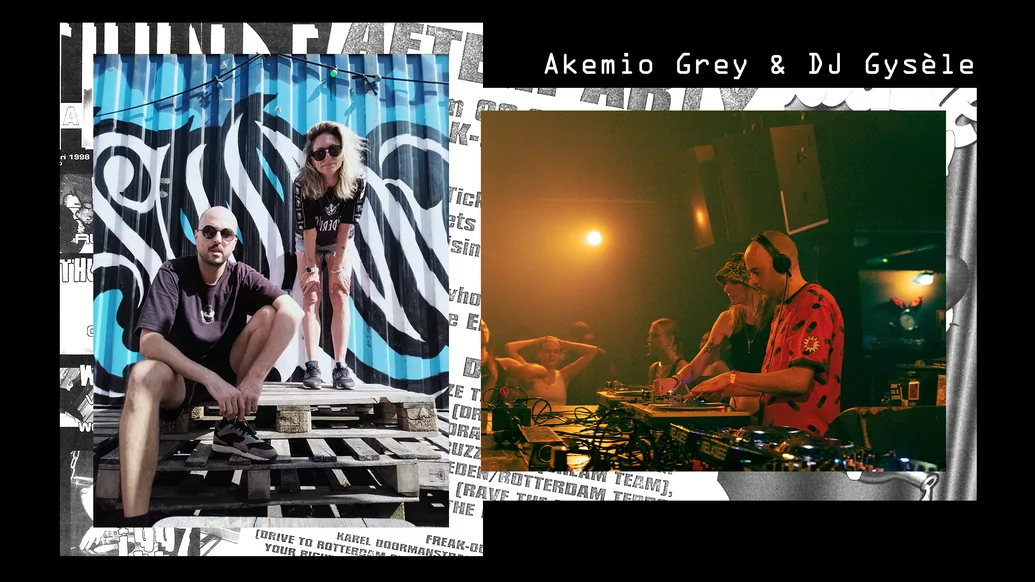

Historic gabber brands like Mokum and Multigroove have managed to stay relevant in 2023 through new talents like Peckerhead and DJ Gysèle, who’s been part of the Multigroove family since March 2022. “Hardcore parties were my first real electronic parties,” says Gysèle, a devoted Multigroove raver since 2003, “so it’s very special that I now play at events in between all of my heroes.” Raised on her dad’s UK rave mixtapes and extensive record collection, she’s been honing her craft as a strictly vinyl DJ at her own ’90s indebted parties, Lang Zal Je Raven.

The more these older brands look outside their remit, the more diverse and enriched this new-meets-old gabber scene will become. Gysèle's newest party, HARD ATTACK at the Melkweg, is a case in point. Launched in April this year and run together with Akemio Grey, from the deepscape trance platform Dreamphase, HARD ATTACK is all about bringing “established names in the scene together with local talents”, she explains, with their most recent event tipping the scale towards young female artists (four of the six acts billed were women). “I see so many great young girls playing early rave,” continues Gysèle, “and mostly playing vinyl, too. They deserve a big stage in our opinion.”

The gabber scene has changed dramatically over the last 30 years. It’s now full of young women in the DJ booth, and more producing behind the scenes. The music is changing too, but there are plenty of artists (Lady Error included) weaving that “old pure hardcore gabber feeling” into records as well as DJ sets. Meanwhile, DJs like Cynthia Spiering, Gysèle and Gabber Eleganza are helping to foster a wider interest in gabber, serving as a bridge between the more purist Dutch scene and other globally dispersed harder styles communities favouring a hybridised post-Net gabber sound. What hasn’t changed is the vibe: that gabber core of outsiders banding together. “Gabber was always a genre for marginals and outsiders of all sorts,” says other Explity co-founder Talita, “so it makes sense that this music stays a soundtrack for our struggles.”

Gabber isn’t for everybody, but everybody can be a gabber. And once you’re in, you’re in it to the end. As Leonie says: “It’s not a way of life, it is my life.”