Overmono: live from the underground

After years in the UK underground as solo artists, brothers Tom and Ed Russell, formerly known as Truss and Tessela, have made huge strides as a duo in recent years as Overmono. Lauren Martin learns how they’ve built a sound and A/V live show that taps into UK dance music legacies, all while staying true to themselves

When Tom and Ed Russell moved into their studio in 2018, they felt the weight of UK dance music history. Housed in the deep south-eastern London neighbourhood of Bromley North, the huge space was something of a wreck when the Welsh brothers got the keys. It was originally home to a magazine printing press; when they ripped the carpets up, there was a patchwork of black ink stains across the parquet wood floor. Pulling apart the wall panels, they found photos of the music studio’s first owners: British dance duo Strike, remembered for their euphoric 1994 hit single ‘U Sure Do’.

Strike kitted the studio out and made it work for a while, soundproofing the floor with densely-packed sand so as not to disturb the church below. But the later, long-term owners Arthur ‘Artwork’ Smith and Danny Harrison — of, among many others, garage projects Nu-Birth/187 Lockdown, and one half of Menta with Smith — made it their own. The brothers found metalwork for records by Grain — Smith’s techno alias, a project they love — and in an adjacent store room, “thousands and thousands” of vinyl records were left in situ by Harrison.

“The legacy in the studio was really special, and we both fed off that,” says Tom, as Ed nods along in earnest. On one wall, next to a dart board, hung the platinum plaque for Daniel Bedingfield’s 2001 hit ‘Gotta Get Thru This’, produced and remixed by Smith. “When we got there I thought, ‘Fuck, some proper big tunes were made in this place. We need to write bangers’,” says Ed.

Inspired by their surroundings, they started creating a sample bank from Harrison’s vinyl collection — “he had so much amazing old breaks stuff” — and bought a 24-channel Allen and Heath mixing desk from Smith, which they began building their setup around. But after weeks of troubleshooting, patching and producing music, they realised it wasn’t what they wanted. They ripped the wires out, sold the mixing desk and started again. They had to figure out who Overmono should be.

Country Rudeboys

There’s no record shop in the small rural town that Tom and Ed grew up in. “I used to nick the compilation CDs off the front of DJ Mag,” says Tom, and they roar with cheeky laughter. (The symbolism of the moment isn’t lost on them, either.) “Well, that and record the BBC Radio One Essential Mix religiously every week to tape.”

Ed was barely a teenager when he started sneaking into Tom’s bedroom to steal his records. A cheap set of Numark decks were the childhood weapon of choice, “but I was way more interested in the effects on the mixer than learning how to mix; I’d just play a record, EQ and filter it, bang some delay on, then start the next one.”

While Ed sold his homemade mixtapes to kids at school, Tom rallied a local crew for free parties and hauled soundsystems into quarries, woodlands and any pub with a sticky carpet and low ceiling that would put up with them; a loyal band of “country rudeboys” raving to roughshod DJ sets of hard house, acid techno, hardcore, trance and handbag house. The memory of being kids who fell madly in love with dance music far away from city clubs and genre tribalism has stayed with them.

“Eventually, Ed gravitated towards drum & bass and I got into techno,” remembers Tom, “but looking back, that lack of access gave us this great sense of naivety; if you don’t know what’s meant to be cool, you’re not judging each other’s tastes and can be genuine about what you like.” Ed agrees: “I always feel like we’re on the outside looking in, and I’m sure that has an impact on our music. We never think about ourselves as gelling with any scene or style. I mean, the only people we’ve ever sent our music to is each other.

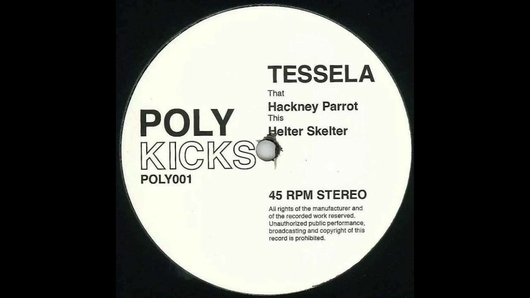

“When people send us their tunes and ask for opinions and advice, we’re always like, ‘Well, it’s up to you. Who am I to tell you how to make your music?’” Ed goes on. “Often, you’ll hear a record for the first time and you’ll think it sounds weird, that it’s just off — but years later, you’ll listen to it again and think, ‘Fuck me, that’s so good, I would never have thought to do that’. I wasn’t going to release ‘Hackney Parrot’ because I didn’t think it was working, but Tom encouraged me to.”

The brothers were on promising paths as underground solo artists before becoming Overmono. Ed is the chattier of the two, endearingly open and somehow still bright-eyed after many a late night in the studio. He spent his teens at drum & bass and jungle raves and his university-age weekends at dubstep dances in Leeds, which lit the fuse for him to produce as Tessela. Pulling also from hardcore and garage, he made killer singles like 2013’s ‘Hackney Parrot’, a grin-and-gunfinger-inducing modern classic that launched Poly Kicks, the record label the brothers run together.

Tom, the elder brother by a decade, had been producing and DJing as Blacknecks with Bleaching Agent, and solo as MPIA3 and Truss. In Blacknecks, he made ruff ‘n’ ready nosebleed techno that asks itself, what would this borderline silly melody sound like with a massive distorted kick-drum under it? Their finest is 2014’s ‘To The Cosmos, Let’s Go!’, which sounds like Patrick Cowley making big room techno. Truss was his most successful alias, though, and saw him release music on the Perc Trax label solidly throughout the 2010s.

They produced one track together as TR\\ER, released in 2012 on the aptly titled Brothers label, but kept the focus on their solo work. Then in 2015, heading home from a Surgeon live show and fizzing with ideas, the brothers decided to write music as a pair. They packed a car with gear, drove out to a rented cottage in Wales and a couple of weeks later emerged as Overmono proper. The dozen or so tracks they made during that trip became the basis of the three-part ‘Arla’ EP series, their first releases on XL Recordings. Ed lights up when he thinks of how they’ve come full circle.

“The first demo CD that I ever sent out in the post was to XL, when I was 15 years old. I mean, the tracks were rubbish, ranging from bad to really bad,” he laughs, “but they actually got back to me and were encouraging. By the time we had our first music as Overmono, XL were still at the top of my list. That’s never changed.”

“I can’t really think of another label like them,” says Tom. “There’s never, ever been any pressure to change what we’re doing. We’ve always worked on our own terms and they just help us do whatever we want; and for the most part, we’ve been pretty self-sufficient.”

“I’d never, ever want to make a tune today that sounds like it was made 20 or 30 years ago” – Ed

Sonic Shift

The release of the ‘Arla’ EPs marked a sonic shift. Tom’s dark techno smog cleared, revealing nimble, braindance-esque melodies. Ed’s knack for clipped vocals-as-percussive loops came over from hardcore, but he sweetened the mood with R&B, swapping out frenzy for forlorn. Even in the early recordings, their respective influences folded into one another remarkably well.

Part of the gear they took to the cottage sessions was a bank of sounds ripped from a brother-in-law’s vinyl collection; a slim selection of Detroit techno, bulked out with promos of ’90s hardcore, trance and breaks. “The ‘Arla’ EPs were my first foray into sampling, actually,” says Tom. “Ed had worked with samples before as Tessela, but those EPs were the first time we’d made tunes that were almost exclusively sample-based. It gave the EPs a more cohesive sound but, frankly, they were an absolute pain in the arse to clear [the rights for],” he says in his low, laconic tone.

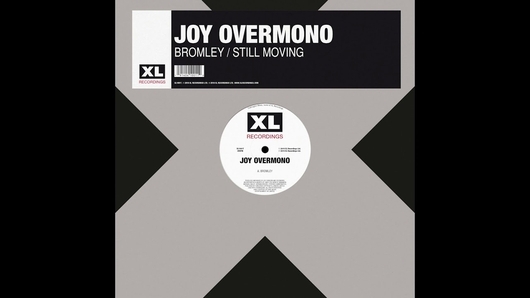

When they got set up in the Bromley studio a couple of years into the project, Harrison’s record collection was a goldmine for thrashing out ideas — the aptly-named 2019 single ‘Bromley’, a collaboration with Joy Orbison, was inspired by the “skippy UK techno” of the Grain era — but they realised that they needed to nail down the Overmono sound, “and so, over time, we sampled less and less”, says Tom.

“Now, the only thing we sample from other people is vocals. We’ll sit with a few beers and trawl Bandcamp for hours and hours, going down rabbit holes to find a phrase or vocal run that can be a hook.”

“And even though we don’t sample other people’s music now, it taught us how to do it ourselves,” explains Ed. “We’ve built a massive library of samples of our own beats; Tom will make a loop, I’ll sample it, make a new loop and add it back to the bank. Over time, we build up multiple versions of the same beats and loops, even just pure noise; tweaking them over and over. It’s taken a long, long time to do, but it means that the backbone of the sound is our own.”

What is that backbone, then? “I love hardcore and I do take ideas from it, but all the old hardcore vocals have been sampled to death and continuing to use them can easily move you into pastiche territory,” says Ed. “We only sample very recent vocals — from the last few years, at best — because we want to make tunes that sound like right now.

“In the drum & bass scene, there used to be all these daft, unwritten rules of sampling — that you can only sample stuff that’s, like, 15 years old — but that doesn’t necessarily make the music interesting. And even if the arrangements aren’t complicated, you still have to be imaginative with it,” he insists, detailing an arrangement style built around phantasmagoric vocal riffs not unlike that pioneered by Burial.

“If I’ve got a one-bar vocal phrase and want to run over four bars to get the energy that comes from repetition, how can we break it apart and re-contextualise it?” On this, he is adamant: “I’d never, ever want to make a tune today that sounds like it was made 20 or 30 years ago.”

Then there are the drums. They’re what Ed always hones in on. “Our drums never come straight from a drum machine. To me, drum machines just sound... flat. If you love dance music, you already know exactly what a TR-808 and a TB-303 sound like — which is why we don’t use them. I want something more dynamic and imperfect that people won’t expect.

“Every part of the drums comes from a different place,” he continues. “Our kick-drum might come from a modular setup, our hi-hats will be live drums we’ve recorded, and claps and percussion will be synth sounds we’ve made; then, we put them all together and process them in such a way that it sounds like they all could have, maybe, come from the same drum machine. That interaction is what makes drums feel alive.”

“It’s about a sense of playfulness, too. Of not labouring over what we do. I like tunes that sound like they were made in one late night session” – Tom

“It’s about a sense of playfulness, too,” says Tom. “Of not labouring over what we do. I like tunes that sound like they were made in one late night session. Our ideas need to be written down pretty quickly, otherwise I find they’re not worth pursuing. I love Actress — his tunes might well take ages to make, but they sound effortless. I also want the mood to be ambiguous; something positive, but also reflective; so that each time you listen to it, your mood changes.

“Someone described our music to us as ‘gary tears in the club’, and that’s a vibe we gravitate towards in other people’s music, particularly for melodies,” he continues. “I love Italo disco for that. Aphex Twin is the don, of course.” More recently, he’s got that vibe from Tirzah, a London vocalist and musician who makes heartbreaking experimental pop. “The first time I heard Tirzah’s ‘Colourgrade’ album, I thought it was fucking dark, but later on, listening to it over and over again, I heard a lightness in it. That’s what I want for us.”

That ambiguousness is a driving force for their recent aesthetic theme. The cover artwork for 2020’s ‘Everything U Need’ EP and 2021’s ‘Diamond Cut/Bby’ 12-inch are photographs of Dobermans, a notoriously stern German dog breed. On the Overmono covers, though — shot by visual collaborator Rollo Jackson — the Dobermans have soft, even goofy expressions. Of all the visual choices, why this?

“Dobermans are seen as very aggressive guard dogs and nearly always have their ears cut and pricked up, but before people start fucking with them, Dobermans are such beautiful, vulnerable, playful animals,” says Ed. “We want to present something that’s stereotyped as one thing, and present it how it actually is: that there’s a gentleness underneath.”

When the pandemic hit in early 2020, the brothers formed a bubble of two and went to the studio almost every day — until developers bought the building and gave them a hard deadline to vacate. ‘Everything U Need’, their first record featuring the Dobermans, was finished just in time. In their last week, they spent six days making the sand-packed floor shake by remixing For Those I Love’s ‘I Have A Love’, and then spent one, final day ripping out every wire, ready to start all over again.

Anticipatory Feeling

Earlier in April, Overmono released their new EP for XL Recordings, ‘Cash Romantic’. The cover artwork follows their recent theme: a Doberman hangs its head and looks shyly into the camera. The tone of the production is inspired by a box of cassettes that the brothers found from those free party days. The memories flooded back, of course, but it was more about the raw contents. For these tapes, they picked vocal-led tracks from their parents’ record collection and mixed them with acid, trance and anything else that might spark an idea.

Blog house and mashup culture went over their heads, they insist, but the sentiment isn’t far off. “You’d try mixing, I don’t know, a Gerry Rafferty vocal into a Chris Liberator tune, pitched down and filtered to shit, just to see what happens,” says Tom. “Some of it was a fucking car crash, but some of it worked a treat. We realised listening back to those tapes that our mindset hasn’t changed.”

The EP’s lead single ‘Gunk’, “is a trance riff with some R&B vocals smashed in”, they say dryly. They’re too modest: in play, it soars. A taut, downbeat melody and a restrained kick-drum keep the energy burning. Vocal phrases are looped and pitched high and bright above the airy bass, until the euphoria bursts through — and dissipates just as fast. There’s even a panning riff that, perhaps tongue firmly in cheek, sounds like a nod to Underworld.=

‘Gunk’ nails the tender, anticipatory feeling built into the Overmono sound: of the country rudeboys who grew up listening to the Essential Mix in their bedrooms, wondering what this blend and that must feel like in fabric’s Room 1; of the coppery scratch of a pill necked on the walk to the rave, and the sticky rush of adrenalin as you turn the corner, hear the club walls thrum with bass and take hurried draws of a cigarette before diving in. And even though Overmono aren’t bright-eyed country lads anymore, it’s a feeling they still want to convey to the masses.

Overmono have been playing live since 2016. Although their show is distinct from their studio setup, the many changes they’ve made to both over the years have informed one another. After they sold the 24-channel Allen and Heath mixing desk back to Artwork, they took a trip from Bromley to the rolling green hills of Exmoor to Devon Analogue Recording Studio, and were inspired by what they saw.

“We use a mixture of hardware and software and want to have all our options available to us at any given time, but it’s surprisingly difficult to set up a studio in ways that will allow you to do that,” says Ed.

“We’ve been to some amazing, established studios in the past and asked to try out a synth, and the owner goes, ‘Sure, give me half an hour to route it’,” he says with an eye-roll. “After being at Devon Analogue, we had the idea to route our own studio as minimally as possible; so that any bit of gear could be used with any other bit almost instantly, without having to spend hours messing around with wires.”

The switch-up was a revelation. Ideas could be run through faster in writing sessions, and multiple pieces of gear were subbed out for harder-working items; from this, attempts to perform exact studio material for the live shows took a handbrake turn. And as in the writing and production process, the show plays to their strengths. Tom works the synths and Ed works the drums; the former with the Oberheim OB-6 and Roland Boutique JX-08, and the latter with (among other, smaller drum machines) the Korg MS-20, Roland Jupiter and a modular setup. This leaner format gives their performances a sense of unpredictability, imbued with elements of surprise.

“The way we make our tunes in the studio naturally means that we could never just run them in a live setup and have them sound the same, because we mix everything in a more analogue way, but it’s also down to the unpredictability of the gear a lot of the time.” Then, Ed rolls out a dry laugh: “Well, that and the fact that our ears are slightly out of tune; we’re about a semitone out from each other.”

“I want to see how big we can get it. I want to turn around mid-set and watch the Dobermans running through a field on the biggest LED screen I’ve ever seen, surrounded by dozens of lasers and strobes. In that moment I think, ‘This is fucking sick. Why should we stop here?’” - Ed

Aiming For The Top

When it comes to British live dance music bands that can draw a serious crowd, you could probably seat them all around a pub table. Developing an act is an expensive and laborious alchemy of logistics, ingenuity, time and patience, and in the 1990s, many breakthrough success stories pulled it off thanks to the serious liquid cash that came from record label deals — and they’re still all crowding the tour circuit today. Now, few contemporary acts could reasonably be called household names in the same way.

The Chemical Brothers reign supreme. Underworld and Orbital have been gigging since the dawn of rave. Faithless, Groove Armada and Basement Jaxx’s legendary singles and vocalist-and-band setups have ignited crowds for decades. Roni Size and Goldie broke through for drum & bass. Aphex Twin and Autechre are the ageing radicals, but their devoted fans pack every show. Before the tragic death of Keith Flint in 2019, The Prodigy were the renegade masters. After a hiatus, the band have just announced their return to the live circuit this summer.

So who’s out there in 2022? The beefy, bass-led likes of Gorgon City, Rudimental, Chase & Status and Dusky are regular touring draws, but barring the band format of Rudimental and Chase & Status, none of these artists have the kind of live setups that could compete with their ’90s, band-led predecessors, or tap into the same sound and aesthetic as Overmono do.

Disclosure orbit the pop spheres more directly now, and while Four Tet can shift tickets in the tens of thousands and up, with a retina-caressing light show and a pedigree that speaks for itself, his discography is more omnidirectional.

The act the brothers share any arguable kinship with is Bicep. The Northern Irish duo have impressed with their clear-cut iconography, hooky, of-the-moment singles and high-spec stage production, but their sound is far more emotive than Overmono’s; tugging on the heartstrings with elements of deep house and pop, and nostalgic riffs that explicitly hark back to the halcyon days of ’90s raving. It doesn’t chime with what the brothers are doing: something crunchier, tougher, more dynamic.

On the other, not-so far side of the industry, arts institutions, concert halls and even dance festivals have taken on the task of The Great British Live Dance Show by booking classical orchestras to recreate garage, grime, drum & bass, trance and house hits, to audiences willing to pay top dollar to take a trip down memory lane. For contemporary live dance artists trying to make something new that can break them out of the underground, while very consciously trying to avoid retreading the past, it’s a lonely table to be sitting at right now.

Considering this, Overmono hit a real sweet spot. They’re not commercial bores, but have a slickness and focus that makes them ripe for a breakthrough. It’s charming that these self-deprecating, Aphex Twin-loving country rudeboys, who used to make jaws swing in sticky basement clubs, have alchemised a sound, look and trajectory that don’t betray one another; transposing an anti-commercial upbringing of jungle, acid and hard house into anti-nostalgic music that feels contemporary and original, and could steal a march on the UK’s biggest live dance bands.

In the summer of 1996, Leftfield played at London’s Brixton Academy in support of their 1995 debut album on Columbia Records, ‘Leftism’. Their fans still talk about the show today, and for good reason: at 137db, the band were as loud as a Boeing 737 taking off; so loud that chunks of plaster rained down from the ceiling. Tom remembers seeing Leftfield perform live at Glastonbury in 2000, around the release of their second album, ‘Rhythm And Stealth’, which was nominated for the Mercury Music Prize and went to No.1 in the UK Album Chart.

“I’d mostly experienced electronic music in confined spaces, in clubs — which I love, of course — so to see the potential for it to be as big as that was very cool,” says Tom. “Hearing their single ‘Phat Planet’ live really impressed me.”

This is the sentiment of Overmono: distilling the energy of the rave into memorable, main stage experiences without sacrificing the fizz and funk of it all. “When you’re DJing, a lot of the experience of performing is out of your control,” says Ed. “We’ve been DJing at a festival somewhere, turned around and thought, ‘Jesus Chr-iiiiist, what are these visuals?’, and laughed it off. But when you start playing live, all of that is in your control. It’s so rewarding to be able to directly translate what you’ve worked on in the studio onstage for an hour, hour-and-a- half. People get the aesthetic straight away.

“Starting a live show is tough, and the first ones you play are just dreadful, [until] you put the time and effort in and take the visuals seriously.”

For a short time in the very early days they did their visuals themselves, but now they have videographer Rollo Jackson, who films and photographs all of their visual work, including their DJ Mag cover. “It’s like, I want to see how big we can get it. I want to turn around mid-set and watch the Dobermans running through a field on the biggest LED screen I’ve ever seen, surrounded by dozens of lasers and strobes. In that moment I think, ‘This is fucking sick. Why should we stop here?’”

So what’s the dream, then — to play live at Glastonbury, like Leftfield did? “Can we do it this summer?” asks Tom with a grin. Glastonbury will have to wait, but maybe not for long. Last November, Overmono were voted the UK’s Best Live Act by DJ Mag readers at the 2021 Best Of British Awards. After a long break from performing during the pandemic, they’ll be returning to the festival circuit this spring and summer, with dozens of performances across the UK, Europe, and the United States. Some of the biggest are the Lisbon and Barcelona editions of Sónar, Detroit’s legendary techno weekender Movement, IMS Ibiza and UK festivals like Belfast’s AVA, Manchester’s Parklife, London’s All Points East and English countryside favourite Lost Village, among myriad others.

“The way I feel about Overmono is that the sky’s the limit, so long as we stay true to what we’re into, and that feels entirely possible to us right now,” says Tom. “XL Recordings have been effortless to work with and, honestly, they let us do whatever we want. With all of that, why wouldn’t we aim for the top?”