We sent two artists back to school to take the UK’s official DJ exam

As exam boards start to include DJing as part of their music GCSE, DJ Mag sent some legends of the artform back to school, and put them through the exam to test their skills...

Late for the school bus, boring assembly, double maths, a quick gossip or kickabout at lunch — followed by a music lesson playing banging techno and house tunes, with some oldschool Detroit classics mixed in. It’s fair to say that school days have got a bit more exciting in the last few years.

While the traditional DJ blueprint to success is well established, there might be another way to start your journey to the top. Following the GCSE reforms in 2016, the music GCSE offered by the OCR, Eduqas and AQA exam boards has been modified so that pupils can now choose a turntable (or CDJ or controller or even laptop programs) as their instrument.

We decided to send the Utah Saints and Denney, two world-class DJ acts, back to school to take the performance element of the GCSE, partly to see how they’d cope under modern exam standards, and also to assess the GCSE syllabus for DJing. Will it give the next wave of DJs the skills needed to make it in an increasingly competitive market? And how effectively can DJing really be assessed, with its many genres, sub genres and styles, not to mention the technology changes that have made the art form evolve so quickly?

MEET THE DJS

The Utah Saints were one of the first arena dance bands, selling out huge stadiums back in 1995 when the current bunch of GCSE applicants weren’t even a romantic glint in their parents’ eyes. With three UK Top 10 chart hits, and another 10 Top 40 singles, the duo toured with U2, re-wrote the electronic rule-book with their Kate Bush-sampling ‘Something Good’ smash, and have since become festival favourites and launched cult breaks label Bomb Strikes. A DMC finalist in 1987, Tim from the Utah Saints is a genuine scratch DJ, as happy dropping mid-tempo breaks as he is tear-out drum & bass or electro.

The other DJ we chose was Denney, a staple of the house music scene for the last 20 years, having cut his teeth at Back2Basics in Leeds, before progressing to huge releases on Hot Creations, a Global Underground mix album and a forthcoming single on FFRR. A go-to hardware tester for Pioneer and an annual guest speaker and lecturer at Leeds Met, Denney regularly took part in DJ competitions as a teenager (coming third in the country at Earls Court in 2001), so he was the perfect DJ to send back to school.

THE EXAM BREAKDOWN

Students have to take the full music GCSE, with a written exam which challenges their understanding of music and counts for 40% of the mark, the performance part of the exam (which we’re testing today), which makes up 30%, and a music composition test, which makes up the rest of the score.

While AQA and Eduqas have loosely adapted the existing exam format to include DJing, OCR have gone a step further and created a more specialist qualification. They’ve opened up their remit to include rappers and MCs for their GCSE and A-Level qualifications, while they also include a ‘My Music’ section of the exam, which allows students to focus on their chosen genres and styles.

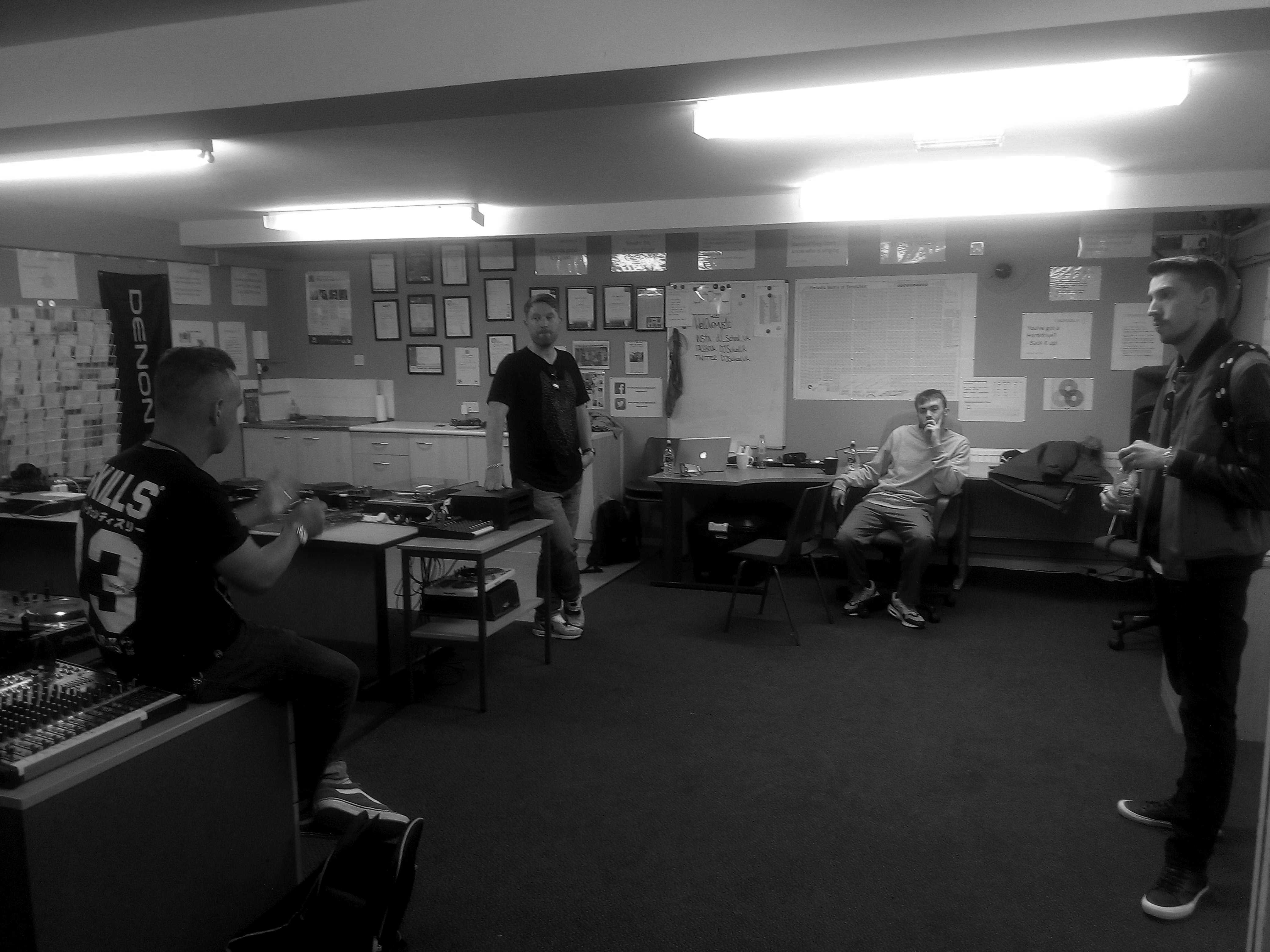

The exam performance takes place at the DJ School UK in Leeds, one of the largest non-profit DJ schools for disadvantaged children, with thousands of students each year, including breaks DJ and recent author of the Little Big Beat Book, Rory Hoy. And, in a neat turn of events, Tim from the Utah Saints is on the board of directors at DJ School UK, making him an obvious choice.

The school is led by Jim Reiss: a renowned hip-hop and scratch DJ who’s played alongside Amy Winehouse, done Glastonbury several times and released his own turntablist album. Jim was also consulted by AQA for the launch of the DJ GCSE, and is an exam invigilator, having put three students through the music GCSE this year — which is why we decided to use the AQA exam criteria.

In 2018, 39,358 students took the music GCSE, with 7,000 of those students using the impressive OCR format, but there are no specific numbers from any of the exam boards on who chooses to use a DJ setup as their instrument. To put that number in context, around 800,000 took maths and English, while 74,621 chose computing, and 62,122 took drama.

THE SYLLABUS

The AQA syllabus states that students must use: “turntables (raw vinyl/CDJ) and/or digital DJ technology (software controller/DVS) to manipulate tracks and demonstrate an understanding and use of a range of techniques. There must be a minimum of two tracks — beat matched, with respect to the structure, tonality and arrangement of the selected tracks. The examiner will assess them on pitch, rhythm, tempo, fluency, dynamics and articulation.”

The examiner will look out for basic skills, including cue stuttering, rewind/spin back, drop ins, EQ and FX; intermediate skills like baby scratches, looping, hot cues and acapellas; and advanced skills such as scratching, hot cue juggling, extended use of acapellas and beat juggling. The students are given four minutes to perform their routine, and three minutes for their ensemble piece, where they have to perform alongside a musician. But to simplify our exam, we’ve given them the full seven-minute allowance, purely for the solo DJ performance.

As with the exam, both DJs get to choose their own setups for the event, with Tim Utah requesting Pioneer CDJ 2000NXS2s, which we very kindly borrowed for the session from Sheaf St, a nearby bar and event space.

UNDER PRESSURE – EXAM TIME

Denney starts. A DJ since 13, with a jazz drummer dad inspiring him to ‘never get a real job’, and a professional DJ by 17 at his local club Empire in Middlesbrough, he arrives bouncing with energy, fresh from three months off putting together his outstanding Global Underground mix. With his normal office a dark, smoke-filled rave packed with hands-up, heads-down dancers at 2am, a sober soundproofed DJ studio in Leeds is a very different proposition. Nervous much?

“The nerves are a different scenario from my normal gigs,” says Denney. “When you’re in a club, people won’t notice if the mix isn’t majorly tight. But in a classroom, any mistakes will jump out. As soon as you get a set of decks in front of me, though, I should feel OK, I’m in my comfort zone.”

Kicking off with ‘Morning Light’ by Proudly People, Denney is quickly into his stride, neatly dropping out the EQ on the kick and using the filter to bring the track to life, accentuating the breakdown. Slickly mixing into his second track, Anthony Attalla’s ‘3D,’ he keeps both tracks running simultaneously, the pumping drum patterns dovetailing nicely, thanks to rolling filters and echo.

It’s then that his house skills really shine through, as the Chus & Joeski ‘El Amor’ acapella bounds in, looped and echoed until it becomes a fizzing stutter, that explodes just as ‘3D’ thumps back into action. With a smooth but energetic mixing style, you can clearly tell that Denney was brought up on a diet of Roger Sanchez, Yousef and Sasha.

“I enjoyed that, yeah!” says Denney as he steps away from the decks. “Did I pass?” A quick look over at Jim reveals a thumbs up and a big smile, with Denney getting 34 out of 36 points, only dropping points for not including an advanced scratch or introducing a fourth sound source.

Next up is Tim Utah, a dancefloor mainstay with over 40 years of experience. And he’s used that experience to curate a very, very different mix. Not content with just testing himself out under exam conditions, he’s given himself the challenge of doing the mix using just Chemical Brothers tracks. He’s also brought in his own Pioneer RMX1000 unit that he uses for every live gig and mix.

“Shall we just go for it then?” says Tim, as he launches into the kind of full-on audio assault that most music examiners will not have heard before (but has the examiner Jim smiling from ear-to-ear in anticipation).

Kicking off by beat-juggling with ‘Hey Boy, Hey Girl’ on a loop, he quickly brings in the Belloni & Nocera mix of ‘Go’, letting both tracks run for a minute, with the acid squelch of ‘Go’ riding below the superstar DJ refrain. Fast and furious, he then uses hot cues to bring in the ‘Salmon Dance’ acapella, letting that breathe for 10 seconds before cross-fading ‘Go’ back in underneath. A looped melodic chorus from ‘Swoon’ gently breaks in, giving the mix a melodic ring, before ‘Star Guitar’ and its windswept breakdown gives the mix more breathing space, as we brace for the MDMA rush of the breakdown. But it’s an absolutely genius double bluff, as he blends it into the Brookes Brothers remix, a tearing double-gun d&b salute. With the seismic Phibes remix of ‘Block Rockin’ Beats’ scratched over the top, it’s an outrageous end to an outrageous mix — seven tracks in seven minutes, plus an arsenal of samples and effects unleashed from his RMX1000.

Still grinning from that very unexpected drum & bass rinse out, we ask Tim how he felt?

“When I did it at home, it was about 30% better,” says Tim excitedly. “My standards are quite high — I’ve got OCD, I try to make everything perfect. I have to finish a job. I can do it again actually, if you want?” Somehow, we can’t imagine many GCSE students saying the same thing after they’ve taken their exam. And the score? Top marks, 36 out of 36.

EXAM FEEDBACK

The three biggest areas of feedback relate to how the technology is used and assessed, how just one exam (and examiner) can cover a wide range of DJ styles and genres using the same criteria, and whether you can realistically judge a pupil’s ability to programme a set in just a few minutes.

“I think it’s a good start,” says Tim afterwards. “But I don’t see how the same exam can test my set, which uses my hip-hop roots the same as Denney. The two sets are worlds apart, but they’ve both got a place in the dance world — how can you judge them on the same criteria?”

It’s a good point. Tim brought his bombastic cut and scratch DMC style to the exam, complete with a swathe of genre-crossing tunes, while Denney brought his house and tech-house finesse, with fine-tuned loops, weaponised filters and smooth mixing: two wildly different styles, but both undeniably brilliant.

Technology can be a contentious issue, with the die-hard 1210 crew butting heads with those who embrace electronic leaps and bounds. Students taking the exam get to choose their own setup, and we can see the reasoning. While industry standard equipment might mean a pair of CDJ2000s and a top-of-the-range mixer, schools (and parents) are unlikely to have that sort of budget, so there’s no stipulation on what equipment can be used. Students employing turntables are given the same mark and consideration as those using an all-in-one console or even DJ software on their laptop: all that’s required is two different sound sources. While that levels the playing field in terms of cost, there needs to be more consideration for the wildly different levels of technology involved in DJing.

Having used an RMX 1000, alongside hot cues, mixed-in-key software and loops, Tim is happy to embrace the technology on offer.

“Most of that set was mixed in key,” says Tim. “Back in the day, I’d sing a track in my head to try and work out the key. But now when you select a track using Rekordbox, it automatically highlights every track that’s in the same key. It’s a good thing, as it uses technology to make sets sound better.”

A vinyl DJ like Tim in his younger years, Denney thinks that the rapid rise in technology is killing the art form, and wants the exam to test the basic skills.

“Technology does all the work for you,” he says. “The art can’t be lost, both as turntablism and the art of mixing and programming. Imagine if you were learning drums for your whole life, had to practice every day to get your grade, and then your DJ mate could come in and press play twice on sync and get a pass? That’s why most of the DJs today aren’t DJs — they’re producers that have had a hit and then go out on the road.”

Denney and Tim are united by the idea of a blind DJ test.

“I’d give them 20 house, jungle, hip-hop vinyl records that are within 5BPM of each other, and ask the student to mix two of the tracks together,” says Tim. “That’s testing lots of things — the rhythm, your beat counting, how intuitive you are on the spot. A lot of times you are put on the spot as a DJ.” Or, suggests Tim, they could make it even simpler and, “cover up the information on the decks so they have to rely on their ears?”

More common ground comes when they discuss the programming aspect of the exam. Technical skills can arguably be demonstrated over a shorter period of time, but DJing as an art form is taking the crowd from point A to point B over several hours via deeper, weirder, funkier, less-travelled, hands-in-the-air moments. It’s about the highs and the lows, about not peaking too early, about unifying the crowd, finding a common groove, about finding that balance between entertainment and education.

“I really feel that the art of programming is getting lost, 100% — they don’t know how to do warm up sets, they don’t know how to set the club up,” says Denney. “DJing is about knowing when to let the groove of the record flow, when you need to step in with some FX. You don’t have to smash it every time. Sasha is the perfect example, the king of mixing — everything is in key, creating moments with the music.”

DOES THE EXAM WORK?

Including DJing in the music GCSE can only be a good thing, legitimising the art and profession at an early age, and providing students with a curriculum that tests their music knowledge, skills and composition. And it’s important to note this is an entry-level qualification for 16-year-olds, with more in-depth options available at music colleges, A-Level grade, B-Tec qualifications, university courses and more.

But how can one exam be expected to compare a traditional hip-hop set as opposed to a blistering techno set, or a happy hardcore throw-down, or one that attempts to juggle disco, funk and soul? With so many variants, how can a turntable, with its inherent beat matching and scratching abilities, be judged on the same criteria as DJ software on a laptop? The two are worlds apart. It doesn’t happen for other music GCSE instruments like the flute or violin or trumpet, which is why more specific guidelines are needed. And with DJ sets lasting hours, how can the exam possibly assess a DJ’s programming over just four minutes, when for techno DJs, that’s when the first track really starts to get going?

All the exam boards that we spoke to said they would be open to our feedback, so here’s hoping that in several years’ time, we have a more robust music GCSE that gives more focus to DJing genres, technology and programming. Until then, choose music, choose DJing (and the OCR syllabus if you can), and turn those tunes up loud at school.

FEEDBACK FROM JIM REISS, EXAMINER

“Having dedicated my life to this art form in all its variants, and having set up a school that aims to help any aspiring DJ whatever their starting point, or whatever their goals, I am as aware as any just how challenging it is for schools and exam boards to try and qualify these skills. I completely agree with all the concerns raised by Tim and Denney. I wrangle regularly with how we can level the playing field for aspiring DJs of all genres to gain certifications, and then how to ensure DJ exams are equal in demand to those available to aspiring guitarists or singers. I am in the unenviable position where I also know how slow it is for education policy to accept and pay decent attention to a new skill such as ours, and how hard it is to train the teachers to reliably assess the skills.

“When I was asked to consult with the exam boards to develop these GCSE specifications, I was overjoyed at the official recognition our music was beginning to receive. I was then extremely surprised that after only a few short discussions, the consultation was considered complete, and the exams published. I am the first to say I can’t wait to have another look at it.

“At DJ School UK, we know we can’t teach anyone how to be a celebrity. We don’t know any guitar teachers who think they can either. We leave that to Disney stage schools. We do know we can teach a range of skills that a young person can use to develop their own creativity, with respect to their own choices of music, and with that approach to the competitive DJ market, or just throw a great house party. We want to develop much more robust qualifications for learners, and nationwide training for teachers, but until one of the big exam boards decides to pay more attention, we are just hugely grateful for this first step in the right direction.”

TIM’S OFFICIAL REVIEW – 36/36

“As expected from a pro DJ, Tim absolutely nailed this — he approached the task with an artistic theme in mind and produced a mix that achieved his vision, and represented his chosen genre extremely well. We at first thought he dropped one point for technical accuracy, but it was proven this was a technical issue (auto load of hot cue function failing), caused by the exam moderators not providing the requested equipment. The mix respected structure and harmony of the chosen tracks using manual platter looping, multiple FX, EQ, an external sampler and multiple sound sources, plus scratching. The sync function was not used, and authentic ‘nudging’ could be seen to maintain the pulse of the mix without affecting the overall flow of the piece, which was a drum-break heavy routine incorporating multiple sections and vocals. By showcasing a range of the more demanding skills available to a DJ at this level, he achieved full marks. This examiner is aware that other skills displayed by Tim are not covered by this marking scheme, especially the ability to cram so many mixes into such a short time, without the use of sync functions.”

DENNEY’S OFFICIAL REVIEW – 34/36

“As expected from a pro DJ, Denney flawlessly achieved his performance with complete attention to the structure, harmony and arrangement of his chosen sound sources. He lost zero points for technical accuracy, expression or interpretation. It was so smooth and the programming of the tracks so suited to the overall piece, that to a layperson, it could have sounded like a pre-prepared remix or one track. The video proves that it was in fact three tracks, one of which was an acapella. He incorporated multiple EQ and FX changes, which showed musical awareness and added to the overall composition. Sync was not used, and manual nudging gave the set a groove specific to this performance and suited to the occasion. Had Denney added one more intermediate skill (say a hot cue edit), and one more sound source, he would have achieved full marks, however to do so, he would probably have had to cram so much into the short time available it may have detracted from the overall flow. This examiner is aware that for a DJ using this genre of music, part of the skill is in programming consecutive songs over a longer period, and that the exam requirements make that particular talent impossible to assess.”

Thanks to Jim Reiss and all at the DJ School UK for their help and support. Find out more about their tireless community DJ work here.