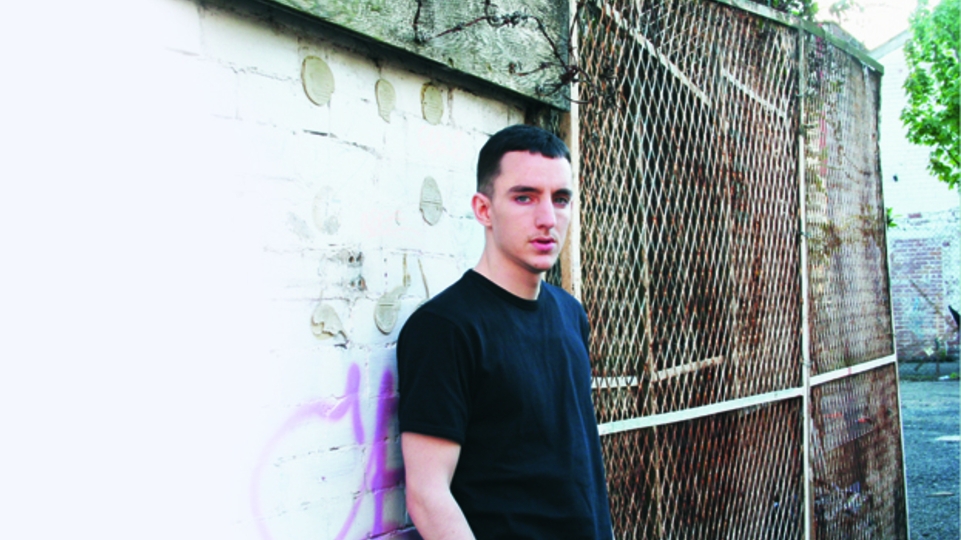

JUST A RASCAL: HYPERDUB'S WALTON

Hyperdub has a penchant for breaking the next big thing

DJs have a tendency to self-mythologise. Their biographies wax lyrical about how they were raised not on nursery rhymes, but Ethio-jazz and obscure funk. How they toddled into the Paradise Garage and underwent a house music epiphany. How their “classical training” (read “grade three bassoon”) is the grounding for “multi-genre collages of texture and sound”.

So judging by 22-year-old Mancunian Sam Walton’s freewheeling collision of industrial techno, UK funky, and percussion that sounds like a collapsing factory, no doubt his earliest musical memories are of rooting through dusty 12”s in Piccadilly Records, or a fifth birthday party where, instead of a clown, Jeff Mills provided the entertainment. “Nah, I think the first electronic record I heard was Dizzee Rascal’s 'Boy in Da Corner',” he counters with a smile. “That’s the point where I first got into it. Before that it was — I don’t know. Whatever was on the radio.”

He’s refreshingly blasé about this route into electronic music, and is happy to admit that it was only that record’s commercial success that led him to explore grime more fully. “It’s probably healthier that the scene stays underground, in a way,” he says, when we ask if he sees parallels between his own route into dance music, and the success of acts like Disclosure. “But it’s good that some bits are commercial, because people who are completely out of the scene, they hear a dubstep record on the radio, and only through that go into the deeper stuff.”

GRIME AND GRIT

His music may be more likely to be found shuddering dancefloors than blaring out of a Blackberry on the back of the 341 bus, but it still convulses with grime’s inner-city aggro, the “rawness” that Walton says stuck out from everything else he was hearing on the radio at the time.

“I’m jealous that I wasn’t in London, with the whole pirate radio thing,” he admits, adding that though Manchester had a grime scene, of sorts, compared to the noises bursting from the capital, it didn’t do much to inspire. “Luckily, the mixtapes were quite easy to access through the internet.”

Had Walton not grown up with the everything everywhere possibilities of online music, it’s debatable whether he’d be producing at all. Certainly he wouldn’t be crafting his ever-so-zeitgeisty smorgasbord of bass and beats, that kitchen-sink approach that’s defined the UK’s dance scene for the last half decade. “I’m young, so I’ve grown up with YouTube, and the internet, and that’s been vital,” he explains. “The accessibility of that stuff’s really important, and if it hadn’t been there then I’d never have discovered a lot of the music that influences me.”

It’s a strange new model, and Walton stands alongside similarly youthful producers, like Disclosure and Happa, who discovered dance music not through clubs, or even record stores, but podcasts and streaming radio. Like them, Walton started producing before he was old enough to get past a bouncer, attempting to make grime beats that he’d send out to friends that MCed, though nothing came of it (“I never really rated Manchester grime artists,” he laughs, “it just sounds better with a London accent”). When he did start going out, it was to “really bad clubs”, and his discovery first of garage, and then dubstep and funky, was led by DJs like Blackdown and Brackles on Rinse FM.

HYPERDUB

At their nexus of myriad influences stood Hyperdub, Kode9’s dubstep imprint that’s evolved since its founding in 2004 to lead the way through UK funky, post-dubstep and other poorly-monikered strands of sub-bothering electronics. Walton began emailing tracks to label manager Marcus Scott.

“He was one of the only people that was actually getting back to me, and telling me what he thought I should do,” he says. “He liked the ideas, but not enough to sign them. It needed to be a bit dirtier and grittier.” A production course at music college had given him studio nous, but the rawness that had so stuck out from those early grime records had been stripped away in the process.

It was Kyle Hall’s 'Kaychunk/You Know What I Feel' EP that broadened Walton’s vision, its resonant swirl encouraging him to dig through the Detroit wunderkind’s back catalogue, and in the process discover the sounds of the Motor City. “I just found his stuff really interesting and fresh. He uses a lot of distorted drum sounds, that kind of thing. But I like the way some of it’s quite musical. There’s a lot of melodies and chords which I think at the moment there’s not enough of. There’s too many tunes that are just drum beats.”

Walton took Hall’s distorted percussion and married it to his dalliances between funky and dubstep for the stomping sub workout 'Aggy'.

Convinced he had something special on his hands, he bypassed Scott and tweeted the Soundcloud link straight to Kode9. “He emailed me asking for a copy because he wanted it to play out. A couple of months later, he rings me up and says he wants to do a release.” A self-deprecating smile. “It was pretty exciting.”

UNIQUE FEEL

Walton’s a reticent interviewee, more at ease discussing the nuts and bolts of producing — “bars and beats and whatever, BPMs and how things are put together” — than its more abstract characteristics. He speaks with a heavy Mancunian drawl, sentences creeping along, and seems remarkably grounded for someone about to release their first album, 'Beyond', on one of the UK’s most groundbreaking labels, with only three EPs to his name.

“He just sounded so different from a lot of the music that comes into my inbox,” says Scott when we ask what it was about Walton that first piqued his interest. “His music sounded like funky and grime, but somehow he was putting his own stamp on it. I asked to hear more, gave him a bit of guidance, and it started from there. Since then he seems to have found his own sound, richer and glossier. But hopefully this is just the start.” And what was it that made Scott confident to give him an album so early? “We wanted to do it, so we are,” he smiles.

The album itself is a blistering whirl of rhythms tough enough to crack cement, ethereal vocal snippets and low-end you could drown in. It’s also surprisingly melodic, the battering ram drums offset by, if not exactly sing-a-long moments, then at least something you could justifiably be humming on your way out of a club. “I try not to stick to a specific genre. With the album, I wanted there to be a feel. There’s an industrial, colourful feel, but not sticking to one specific genre. People find it less boring that way.”

On those terms, you certainly can’t accuse Walton of being boring. Across only a handful of releases, and an impressively mature debut album, he’s bounded between styles like a puppy between scents. So what can we expect next? “There’s so many genres that I like at the moment, I’m finding it hard to know what to make. Unless I’m going to merge them all together and make something really mad,” he teases, with a knowing smile. We await the next chapter in Walton’s story with baited breath