Game Changer: How Tangerine Dream's 'Phaedra' set the template for ambient electronics

Coinciding with the release of a major Tangerine Dream retrospective, DJ Mag catches up with Peter Baumann, one third of the band’s classic line-up, to discuss the enduring influence of the German electronic outfit's fifth album

One of the curiosities of psychedelia is that, until 1967, American “happenings” had been mostly sound-tracked by electronic music. Then, as soon as acid trips and cultural liberation became widespread in the US, machine sounds were replaced by folk guitars, The Grateful Dead, and hippies.

But in Europe, the exact opposite happened. The psychedelic era saw European music embrace electronics with a grip that’s remained throughout almost every subsequent genre, including glam, prog, disco, post-punk and synthpop. Nowhere was this more obvious than in Germany, where the country’s post-war Elektronische Musik traditions came to the fore. Tangerine Dream are perhaps the definitive example of this cross-pollination.“We never considered ourselves to be part of psychedelia, but we were by default,” says Peter Baumann, who was a member of the group’s classic line-up.

“Acid and pot were popular, and we made mind-expanding music because we didn’t have songs. It was about atmosphere. Our sets were all improvised, half hour-long tracks. In America, psychedelia became linked to the Woodstock and Monterey festivals. The bands were often folk, and they had ‘flower power’. We didn’t have that. We got a glimpse from America, but it wasn’t as pronounced. And rock & roll is really American music born out of blues. In Germany, there wasn’t much blues, and there were very few rock bands. But electronic music seemed to suit the German mentality.”

Formed in 1967 by Edgar Froese, Tangerine Dream had already seen four previous incarnations before Baumann joined. But its best-known line-up was as a trio between 1970 and the end of that decade, consisting of Froese, Christopher Franke and Baumann. It was this line-up that recorded the band’s first releases, including the iconic and contemporary-sounding ‘Phaedra’, the title track of their equally seminal LP. Tangerine Dream formed in Berlin at the height of the Cold War, where there was surprisingly little going on. “It was strange having tanks going back and forwards in front of our school,” Baumann says, “but I was only eight when the Wall went up, and it didn’t worry me much. On a day-to-day basis, it was very quiet. I just hung out with my friends, smoked pot and listened to music. There were American soldiers, so they had GI clubs, and I played with a covers band. I played organ, and we’d play anything GIs wanted to hear.”

While Baumann was entertaining the troops, Froese and Franke were taking Tangerine Dream around a very different circuit. “I was aware of them and a few bands, like Can,” recalls Baumann. “Then I met them at an Emerson, Lake & Palmer concert. I stared chatting with this fellow with long, dark hair, which was Christopher. I said I was playing pretty boring music in clubs, but I was doing experimental music on the side. He asked where I lived, and a couple of weeks later I got a note saying he was looking for a keyboard player.” The first time Baumann got to hear Tangerine Dream was at his audition. “We set up in a basement, and I asked them what we were going to play. Edgar said, ‘Just play’. So Christopher, who mostly played drums then, made some noises. Edgar played some guitar, and I played the organ. At the end Edgar said, ‘that’s cool’. That was it.”

For their first year together, Tangerine Dream spent a lot of time in Froese’s flat listening to new releases. “Pink Floyd were always top of the list. We’d listen for hours and smoke joints.”

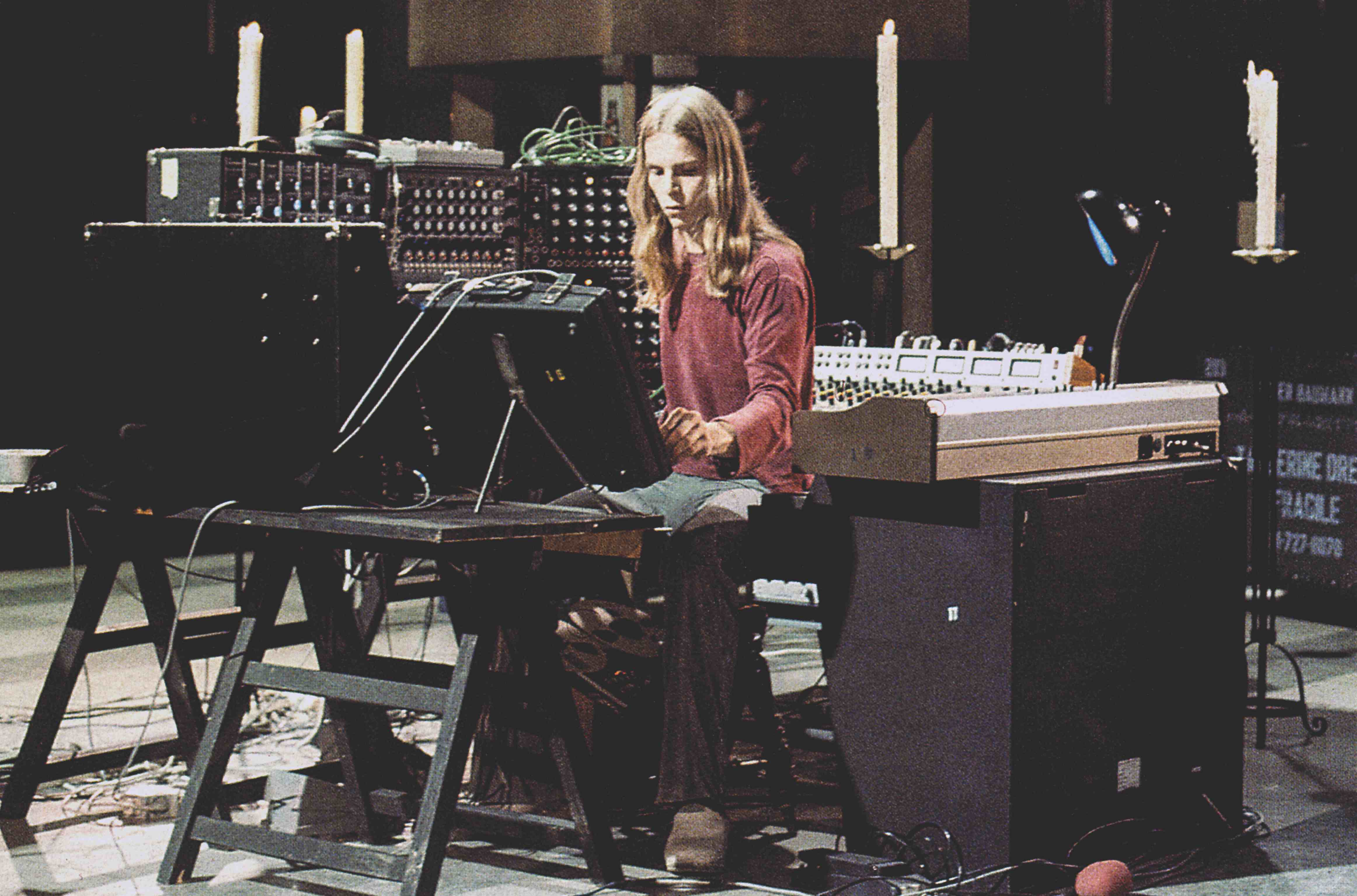

Alongside influences such as Pink Floyd, they began drawing ideas from music theorist/composer Herbert Eimert and experimental composer Karlheinz Stockhausen, and German conservatoire music. “It was from the classical side. There were no bands doing that kind of music, it was the avant-garde.”Soon, they were experimenting with rudimentary equipment and re-modelling traditional instruments. “We were mostly playing keyboards or synthesisers,” Baumann says, explaining how he ended up playing a flute. “But the flute just has such a cool sound, and we couldn’t create it on a synthesiser. At the time we didn’t have any samplers. We just had a little box, and it had a knob that was a sound generator. So you could change it from peak noise to white noise. That was the very first electronic effect I had. Not long after that, I got an EMS synthesiser from England — that was our first real one.”

The band released their first music in 1970 through Ohr Records. The mention of the label’s name elicits a guffaw from Baumann. “We were touring all over Germany in our VW bus, getting paid a couple of hundred bucks a night at small clubs. Then a record company said we could go to Cologne to make some noise in a studio. It was a very small label, but we were happy to get a record out. Our concerts were really sheer luck. It was risky, but exciting and unique, and it was pretty much the same in the studio. We set up our equipment, turned down the lights and started to play as if it was a concert. It was an improvisation.”

“Richard called and said, ‘Hey, I’m starting a record label, and if you have time, can we talk?’ Richard said we could come over to record in Oxford, where he’d got a recording studio. It was in a really nice country manor. But when we arrived, there was nobody there. We finally found everybody — they’d been eating hash brownies and were watching movies in the basement. They could barely show us our rooms, but we settled in and began working the next day. We started recording, and then it was 12 hours later. ‘Phaedra’ was the first track. Christopher had just got a Moog sequencer and was noodling around on it. I was with Edgar in the recording booth and said, ‘This sounds cool, let’s record it’.“I was doing most of the mixing, so I was instrumental in beginning ‘Phaedra’. I would take a lot of reverb and send the reverb onto delays and back through other delays. It was all very atmospheric.”

The resulting track set the template for ambient electronics, while the pads and washes also formed part of contemporary dance music’s make up. Nonetheless, the band were taken by surprise by its success. “I remember being on holiday in Italy and getting a call from Richard saying I had to come back, because we were in the UK charts. I didn’t even know what that meant.”

In the end, Tangerine Dream spent 15 weeks in 1974’s UK charts, even though the 17 minute-long track had got virtually zero radio play: “We were just not thinking about these things”.“It was nice getting attention and going all over England to do interviews,” Baumann concludes, “but it was extra nice because no one believed this weird music could get an audience."