CABARET VOLTAIRE: FORGING THE FUTURE

Sheffield's Cabaret Voltaire were way, way ahead of their time.

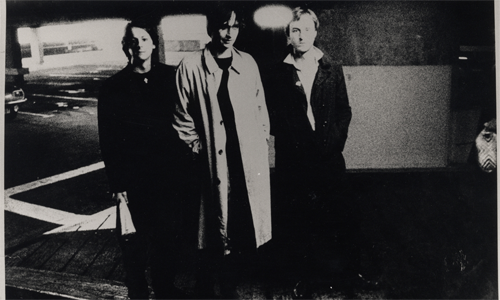

Sheffield's Cabaret Voltaire were way, way ahead of their time. Creating a challenging sound that soaked up electronics, dub, found sounds and scuzzy punk, their sonics were hugely influential on the creation of industrial, house and techno. And it wasn't just their radical sonic agenda, but their political stance, too, that made them unique. If any act is in need of reappraisal today, it's them, and a new reissue series from Mute aims to achieve just that. Neil Kulkarni talks to founder Richard H Kirk about apathy, necessity and house music...

“It just seemed that it was young people's job to question the status quo, question what was being said. I wouldn't say that's been totally lost since, but it frequently doesn't even occur to most people making music to use music for those purposes any more. For us, it was the whole point.”

Richard H Kirk, Cabaret Voltaire

In 2013, Cabaret Voltaire's music sounds as unique, as cuttingly incisive, as accurate and as devastating as ever. 'Red Mecca', the Sheffield three-piece's astonishing look at paranoia and global turmoil from 1981 is being reissued by Mute (remastered by Stefan Betke aka Pole) to preface more substantial remasterings and reissues to come later this year (including a collation of all the albums they released between '83-'85 and a larger '78-'85 collection to come in early 2014) and Richard H Kirk, the group's sole remaining member and custodian of the legacy is finding it odd revisiting and being re-interrogated about music that's 30-years-old but that still hits you like it was made tomorrow. “I'm not someone who sits around listening to my own music,” he admits, “but all the remasterings have obviously had to be okayed by me which has meant listening to things I made an age ago. It still sounds intense. It still sounds like it fits in with when it happened, but also that it doesn't fit in anywhere.”

Cabaret Voltaire, made up of Kirk and fellow bohemians Stephen Mallinder and telephone-engineer Chris Watson, began in the mid-'70s, taking Dada, surrealism, the psychedelic rock of their youth, the art-rock and glam of Bowie, Roxy and Eno and the black music that formed the backdrop of their East End Sheffield heritage and using tape machines, found equipment, oscillators and a love of William Burroughs cut 'n' paste writing techniques to create their own ferocious take on Musique concrète. “When we started we were massively influenced by Eno's ideas that you didn't have to be a musician to make a sound. We didn't even have a proper synth when we started, just things Chris made from electronics magazines and spare parts.”

So did you ever consider yourselves 'musicians'?

“No, that only came later as we got better! As well as all that avant-garde influence, though, we were also reflecting our backgrounds. In the '60s and '70s it was just a fact that working class kids were into black music more than anything. Tamla-Motown, reggae, dub, funk, soul. I think the first dub thing I heard was on John Peel, Keith Hudson's 'Pick A Dub'. I couldn't believe what I was hearing. We used to go to a record shop in the East End, in the Wicker, called Windmill Records. David Rodigan actually used to work there, and I remember later reading that Adrian Sherwood used to bring up dub-plates and records from London to sell there. And of course, because mainstream clubs were so threatening and violent and played terrible music we used to go to a lot of shebeens and blues parties as well. They were just brilliant — they opened after the pubs had shut, you could have a spliff and a can of Red Stripe and maybe something else to keep you dancing and you'd come out at dawn. That listening and experience really affected the future direction of Cabaret Voltaire.”

NECESSITY

After exhausting the possibilities of attic recording CabVol really took things to the next level by finding/founding their own studio, Western Works in Sheffield's industrial district and finally being able to kit it out (with the help of Rough Trade) with something approaching a recording set-up, a multi-track tape machine and a mixing desk. As ever, CabVol touched on something ancient and futuristic in both their methods and sound — looking back to spaces like Can's Inner Space and Kraftwerk's Kling Klang studios, as well as sideways to Lee Perry's Black Ark set-up, but also in a weird way predicting the kind of independent D.I.Y self-sufficiency that so many contemporary artists now call their modus operandi.

“Western Works was like our own version of Warhol's Factory,” admits Kirk. “More important than anything else, it was a place we could hang out, have a spliff, create freely. When we played in Watson's loft we'd get complaints about too much noise but in Western Works no-one interfered. I used to sleep there sometimes rather than stay at home with my parents.

It was somewhere to go after closing time, but also we could finally start properly making music. We had a four-track and then an eight-track tape machine, and it was amazing just to finally start bouncing things around, work within the space, get that kind of tape compression feel that we loved in the music we listened to. And that changed how we saw things because we were becoming better musicians.” So even if by modern standards the technology was limited, you found it liberating? “Well that's the thing about technology. You can get a million plug-ins now that can replicate those sounds but that's not the point — if you're given so much possibility by technology it can actually end up making creativity difficult. Working within limitations is what forces things out of you. In the same way our limitations as musicians meant we obviously couldn't play like Miles Davis or a lot of the black music we loved, but that's what's unique about Cabaret Voltaire, it's our own twisted take on those things, playing against our own limitations as players but also the very cheap technology we had to use.”

CabVol's newfound freedom in Western Works birthed a still-stunning run of albums that include 79's 'Mix-Up' and 'The Voice of America', 1980s mini-LP 'Three Mantras' and finally 'Red Mecca'. Prefiguring and massively influencing the worlds of techno, industrial, IDM and even d&b, Cabaret Voltaire's mix of sounds and uniquely paranoiac style mapped out the feel of their time like nothing else, 'Red Mecca' being perhaps their most cohesive masterpiece. Watson left for a career in film sound after the following year's '2x45' set of 12”s — by then, the reverberations of what Cabaret Voltaire had already done were starting to be felt beyond Sheffield. The next period of CabVol saw them signed to Virgin/Some Bizarre and making music directed at the feet and the dancefloor.

Not so much a change in direction as a purification of the impulse and a reflection of their changing, growing-up personalities. “We've always loved dancing! In the early '80s we started being incredibly excited by what we were hearing coming out of the New York electro scene — Mantronix, Afrika Bambaataa and we also started hearing music from Chicago and Detroit that totally changed the way I felt about music. I'd never heard anything like those early Farley 'Jackmaster' Funk 12”s and stuff like Derrick May. So minimal but so beautiful and because we were travelling and touring more, we got to hear this stuff where it was born. When Cabaret Voltaire started up the intent was aggravation really, it was always quite harsh, quite unforgiving, almost anti-musical. Hearing early Detroit techno really made me think more about warmth and melody and start to try integrating that into the music we were making. It was amazing going and working with people like Marshall Jefferson in '85 and '86 and even more amazing knowing that people like Derrick May were actually citing us as an influence on them, alongside Kraftwerk. That was astonishing.”

ACID AND DUB

Since CabVol's early days Kirk had always been releasing solo stuff under a variety of different pseudonyms but the explosion in club culture towards the end of the '80s gave his solo work, particularly the renowned work under the Sweet Exorcist (on the then up-and-coming Sheffield imprint Warp) and Sandoz monikers, even more impetus and direction.

“Sweet Exorcist really came about through being friends with DJ Parrot who used to play techno in '85 and '86 and used to DJ on Cabaret Voltaire tours. A lot of my solo work has been my take on these musics that I've been exposed to, and my response to the fact that in the late '80s, perhaps thanks to certain chemicals, clubs stopped being these threatening macho places and became again like the vibe I remembered from the blues parties and shebeens. Sandoz was my take on actually travelling to the places that had been making this music I'd listened to all my life. I've listened to Jamaican music since I was 14, but I only got to go to Jamaica in the '90s and for the first time I was travelling not for work, but for my own pleasure. Being exposed to just how much music is part of the bloodstream in Jamaica reminded me of being at shebeens and seeing these guys set up these speakers made out of wardrobes! Just a dedication and fascination with sound and volume. I also got way more into dancehall, the way those beats are made, and then I came back to Sheffield and made the Sandoz albums.”

ANGER TO APATHY

What's been great about Kirk's solo work is that it's always got a little bit of grit and grime and his own immediate environs imbued into the grooves.

“Yeah, it's not 'correct', it's my take. So it always ends up a bit wrong. I've always come back to Sheffield 'cos I can afford it and my family are here so my music's always touched by that. Phil Oakey, Richard Hawley are the same. Starting to not like the winters though!”

Currently, as ever, working on new music (“I found a mid-'80s MXR drum machine and I've been sampling that and have made about two hours of totally new music”) Kirk admits that he misses the spirit of innovation and intrigue that so characterised CabVol's massively influential work. In a time when CabVol's influence is clearer than ever, yet the political legacy of what was enacted in those early '80s years is still bequeathing divisiveness and despair, he's a little surprised at how the supposed limitless possibilities of modern music production are yielding such dwindling returns so often.

“Music became entertainment, pure and simple,” he reflects. “When we were making 'Red Mecca' we were reflecting the realities of a world being torn apart by war and religious division, reflecting what Thatcher's new government were doing, the cutbacks, the destruction of the unions, the victimisation of the poor. I see all that still happening, faster, harder, more violently than ever before, but not much music reflecting it. I think in the '80s fundamentally the counter-culture was destroyed and it all became about money, success and fame.”

Is there anyone at the moment you think is bucking that trend?

“I went to see Factory Floor last year and they blew me away. They seem to be coming at things with the same spirit we had. I don't go out any more so I might not be the right person to ask. I guess if you have a generation of people who've learned that music is something you don't pay for things become devalued — coupled with a culture of attention-deficit it means that no-one really takes the time to challenge the status-quo.”

Will that ever be recaptured? “Oh yeah. Every now and then people remember — music should always come from one place, the middle of your chest.” Hear 'Red Mecca' and be inspired all over again. You get no rewards for being ahead of your time in music, but it's time Cabaret Voltaire got rediscovered by a new generation, if only to realise that being OF your time is perhaps the bravest thing of all. A still-unique voice. Long may it speak to all of us. From the middle of the chest.